As a selection of her work goes on display as part of this year’s Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize in London, the image-maker opens up about the striptease series that kickstarted her career

Photographer Susan Meiselas has dedicated her life to capturing complex, sometimes horrifying, experiences, using her camera as a means of “mediation” between herself and her subjects. She doesn’t try and provide answers to the scenes unfolding before her, but instead poses questions and explores new perspectives. One of her most potent bodies of work centres on the people of Kurdistan in the wake of Saddam Hussein’s genocidal campaign against them in the late 80s – a selection of which is currently on display at The Photographers’ Gallery in London as part of this year’s Deutsche Borse Photography Foundation Prize. Meiselas has been nominated for her first European retrospective, Mediations, which showed at the Jeu de Paume in Paris last year, offering valuable insight into the Magnum photographer’s groundbreaking career – including what is arguably her most formative series, Carnival Strippers, begun in 1973.

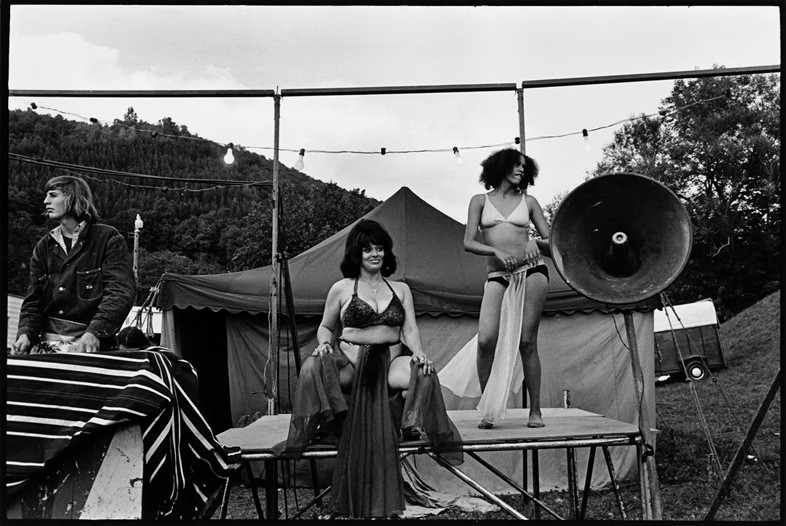

Carnival Strippers is a radical behind-the-scenes peek into the world of smalltown carnival striptease, taken over the course of three consecutive summers just as the women’s movement was beginning to gain traction. “I think in truth it was really the turning point for me,” Meiselas tells AnOther. “Before that I don’t think I had a vision of what it would mean to be a photographer.” Meiselas was a 24-year-old Harvard graduate working as a photography teacher when she stumbled across the carnival strippers, while tailing touring circus troupes during her summer vacation. “It was an accidental encounter, like so much of my work,” she says.

It was early on in her contact with the carnival dancers that she took the shot that ignited her curiosity: Lena on the Bally Box – showing a young, scantily clad women posing on a stand, seemingly oblivious to the stares of the men surrounding her, gazing straight ahead with a detached, self-assured expression. “[That was when] it all made sense... I just felt magnetically, ‘I need to know more,’” she said in a lecture for MoMA. “There were so many issues for me looking at the woman [who I would later know as] Lena. The idea of projecting a self to attract a male gaze was completely counter to my sense of culture – to what I wanted for myself – so I was fascinated by women who were choosing to do that... The feminists of that period were perceiving the girls shows as exploitative institutions that should be closed down so I was actually positioned in the place of feeling these voices should be heard, they should self-define as to who they are and what their economic realities are.”

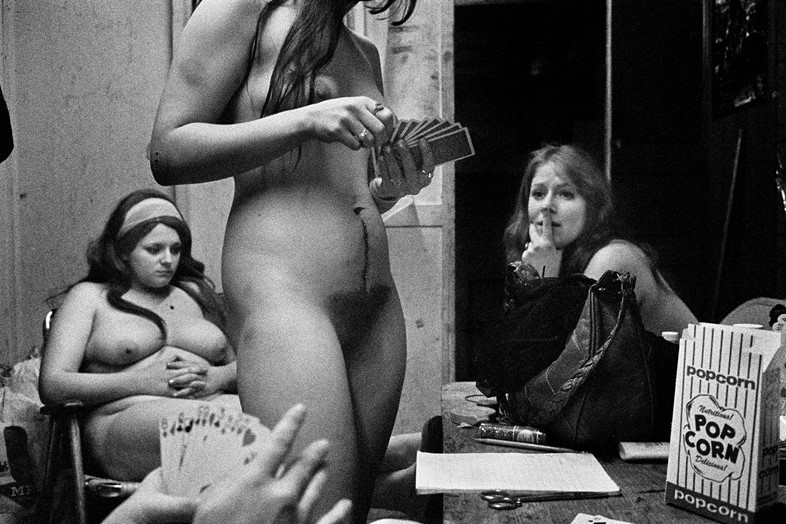

And Meiselas really did want the women’s voices to be heard – directly – so she began recording sound to accompany the exhibition of her images, snippets of which would later be transcribed for a photobook of the series, first published in 1976. These audio clips present a variety of viewpoints – some women feel demoralised by their job, and describe putting up a mental barrier between themselves and their audience in order to survive; others feel empowered in the role, in control of their image and their sexual prowess. For almost all of them, meanwhile, the main objective is financial security and independence. “If you want to be your own woman, to be a single person, you can’t do a hell of a lot better than that,” says former showgirl, Patty. Meiselas also includes the male perspective in her recordings – from the girls’ managers to their clients and boyfriends – in order to paint a fully-rounded picture of her subjects’ universe. For, as Lena says, “being a stripper is as close to being in a man’s world as you can be. It’s a tough life. You need strength and character. The men depend on you – to entertain them and to bring in money for them.”

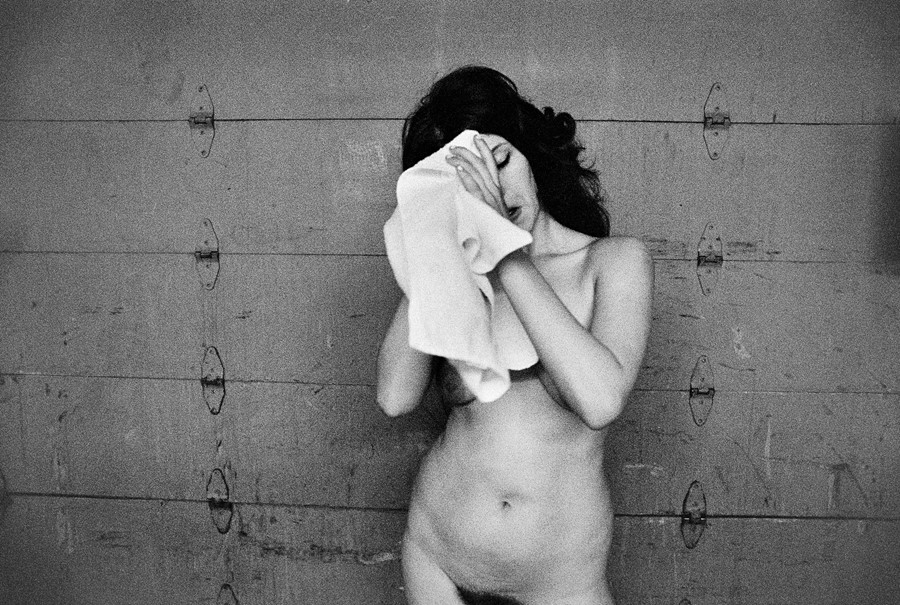

Meiselas was similarly determined to document, visually, the various facets of carnival life for the strippers. There are the shows themselves, of course, where she captures both the viewpoint of the dancers – looking down upon the lustful clusters of men at their (high-heeled) feet – and that of the all-male audience (“no ladies and no babies” at these shows), gazing up at the women’s elongated legs. But Meiselas, who has a knack for befriending her subjects, was also invited backstage by the women to document the hustle and bustle of their changing rooms, their interactions with one another and the mundanity of their lives between shows – the card games, the cigarettes, the endless sitting around.

The result is a truly revolutionary study of what artist Martha Rosler pertinantly describes as “an unappreciated, unloved class of women, who were certainly not admired for their professions at a time when women were exploring what it meant to have a body, and what it meant to have a job... [It talks] about them as fully realised subjects without glorifying what they do to make a living.”

For Meiselas, Carnival Strippers was an artistic and ethnographic revelation. “It gave me a sense of the connectivity [that photography] required and was the catalyst for finding a form to represent experience,” she tells us, noting how collaboration with her subjects and the use of multiple media has remained vital to her work ever since. “Just last week we held a workshop for members of the Kurdish community, inviting them to come and contribute their stories to what I’m calling a story map installation for the Photographer’s Gallery show. I think Carnival Strippers made being a photographer coherent for me as a way of working in the world.”

The Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2019 exhibition is at The Photographers’ Gallery until June 2, 2019.