These pioneering women artists challenged the conventions of the day to become pivotal in the creation of Bauhaus

As admirers of the famed Bauhaus movement celebrate the centenary of the most progressive art school of the 20th century, publisher Taschen and author Patrick Rössler are telling the stories behind the oft-forgotten, but ultimately pivotal, female students and educators of the era in a new book. While the institution presented women in art and design with unprecedented opportunities to explore their fields and be acknowledged as legitimate professionals, it is too often forgotten that they were simultaneously battling unreasonable family expectations, the ambiguous and contradictory attitudes of the faculty and administration, outdated social conventions, and, ultimately, the political repression of the Nazi regime. Here are five Bauhaus women you might not have heard of, but should get to know.

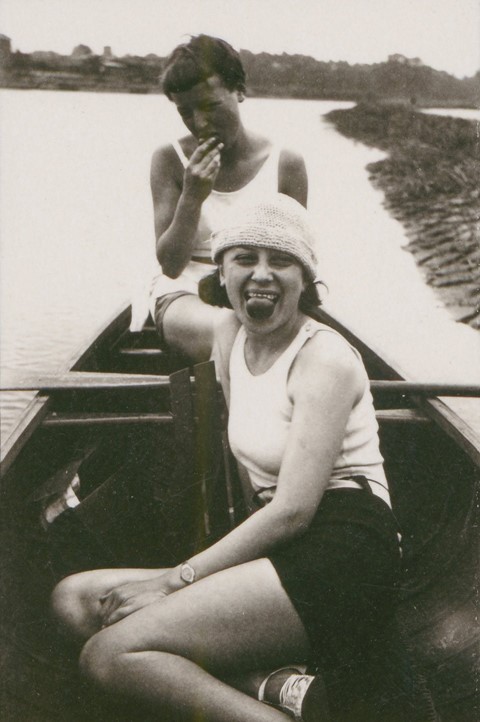

Gunta Stölzl

Like many women of her generation, German textile artist Gunta Stölzl’s career featured unexpected turns that saw her transition from studying decorative painting, glass painting, ceramics, art history and style at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Munich from 1914 to 1916, to working as a Red Cross nurse during the first world war. In 1919, having briefly re-enrolled at the Munich institution, Stölzl began studying at Staatliches Bauhaus Weimar. Completing her studies in 1925, she was immediately positioned as a master of the weaving workshop, and subsequently became the department’s director. Stölzl is remembered as the only female Bauhaus master, placing her at the centre of many discussions surrounding the school’s controversial and sometimes conflicting views on gender equality.

Otti Berger

When Stölzl left her role as director of the Bauhaus weaving workshop in the autumn of 1931, she suggested that Croatian designer Otti Berger should take her place. Despite actively fulfilling the requirements for some time, she was never formally appointed and the position was eventually given to Lilly Reich, with Berger as her deputy. Less than a year later, the Croatian designer left the Bauhaus to open her own studio. Despite much success post-Bauhaus, the artist’s career was cut short in 1936 when she was banned from working in Germany due to her Jewish origins. Having failed to join her creative peers – including fiancée Ludwig Hilberseimer – in the US, struggling with her mother’s illness and being forced to accept an inability to find work in the UK, Berger was forced to return to her hometown of Zmajevac. Tragically, the designer and her family were deported to Auschwitz concentration camp in April of 1944, where she was murdered.

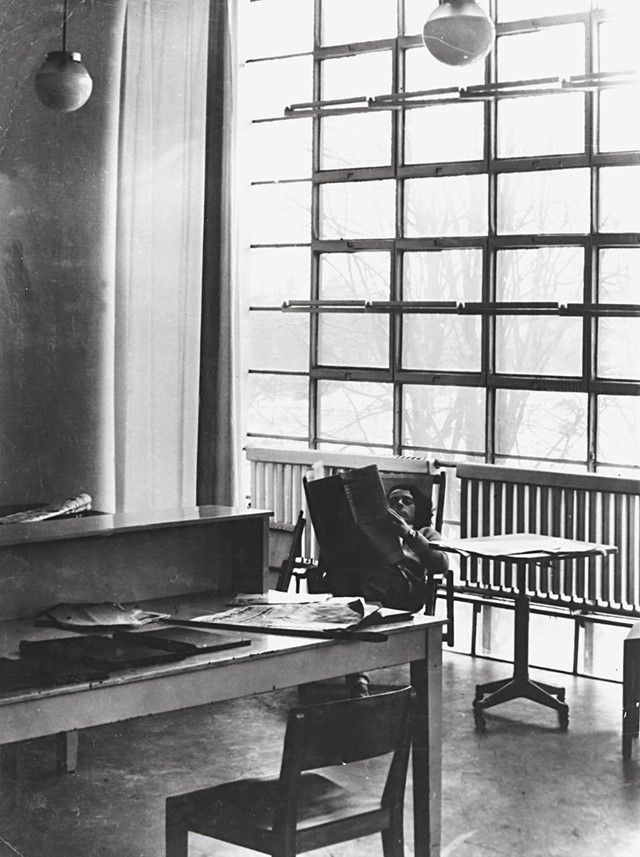

Irena Blühová

Irena Blühová is one of very few Bauhaus alumni to have engaged with the activism-led art of social photography. Prior to joining the school in 1931 she worked as a secretarial assistant and later a bank clerk. From 1922 until 1926 she studied – while also working at the bank – at the languages- and science-focused Realgymnasium in Bratislava. She soon found an outlet for these interests in photography, taking her first tourist photos and starting a number of series that were published in recognised journals. Discovering the Bauhaus and its specialisation in architecture, typography, photography and advertising through a magazine article, Blühová attended after a preliminary course with Josef Albers and studied at the school for one year. Following a successful career as a photojournalist, Blühová worked in the illegal anti-fascist movement from 1941 until 1945, and from 1945 to 1948 was co-founder and director of the publishing house Pravda.

Elisabeth Kadow

Daughter of a Bremerhaven architect, Elisabeth Kadow (née Jäger) began an apprenticeship at the Weimar Bauhaus school, aged 18, under the guidance of tapestry artist Irma Goecke. Celebrated for her achievements while studying textile technology in Berlin and Dortmund, she was offered a role as a specialist teacher in the field, in Dortmund. By 1939, she joined Georg Muche as a master’s apprentice at the Textilengineurschule (textile engineering school) in Krefeld. In 1940 the weaver, painter and graphic artist married Gerhard Kadow and started teaching a fashion class, later progressing to artistic print design at the Higher Technical College for Textile Industry. When Muche eventually retired from education in 1958, Kadow took over the leadership of the master class for textile art and her international reputation grew immeasurably. Until 1971, Kadow led the entire design department of the textile engineering school and, upon leaving the school, she devoted herself to design work, armed with a lifetime of inspiration taken from textile art. She created elaborate embroidery and, working in collaboration with Nürnberger Gobelinmanufaktur and the weaver Johann Peter Heek, produced outstanding artistic tapestries.

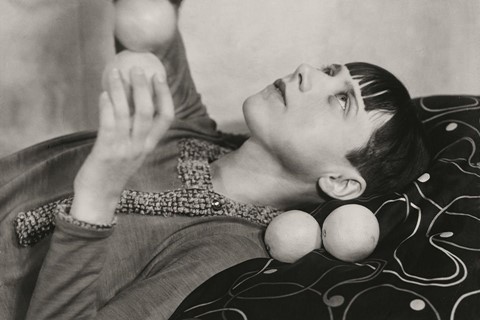

Marianne Brandt

Recognising her design prowess from an early stage, Bauhaus professor, painter and photographer László Moholy-Nagy championed Marianne Brandt’s groundbreaking presence at the school as she broke rank among gender stereotypes, thriving in the male domain of the metal workshop. Brandt’s objects for everyday use are still hallmarks of the Dessau Bauhaus and she is celebrated not only as a pioneer in metalwork, but as a leading female figure in an aggressively masculine industry. Despite her successes and the fact that she far out-performed the majority of her peers, Brandt is rarely mentioned in the same breath as her much-discussed male colleagues.

Bauhausmädels: A Tribute to Pioneering Women Artists by Patrick Rössler, published by Taschen, is out now.