“We’ve always been here. We’re not going anywhere, so, y’know, deal with it.” As the Museum of Trans Hirstory and Art features in new exhibition Queer California, founder Chris Vargas tells us why the nomadic museum is so crucial

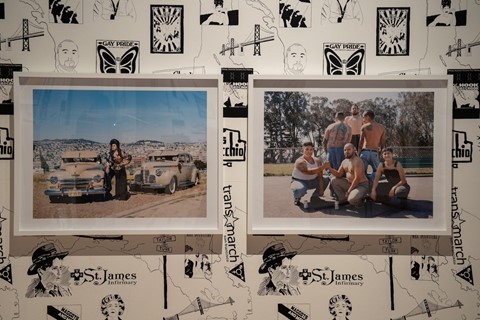

The most recent iteration of the Chris Vargas’ Museum of Trans Hirstory and Art – commonly known as simply ‘MOTHA’ – is an archival and artistic history of San Francisco’s Bay Area, and currently resides in the Oakland Museum of California as part of their just-opened Queer California: Untold Stories exhibiton.

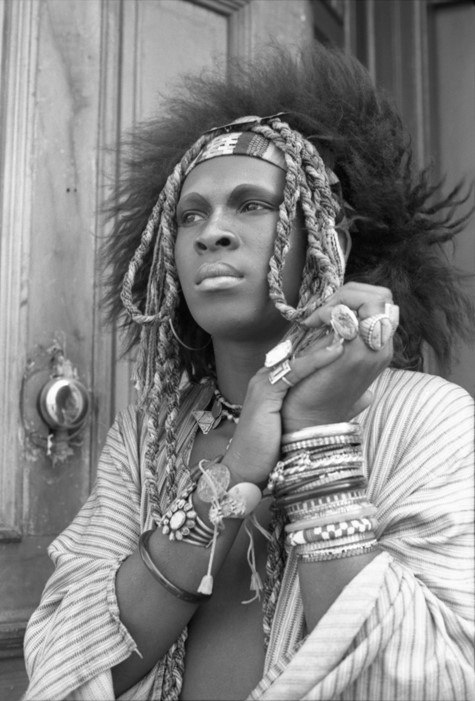

MOTHA is nomadic, and claims spaces for trans histories within existing institutions. It is led by Vargas, a filmmaker turned “reluctant curator” of the museum in 2013, and was created with the aim of building on the often sparse trans history so far preserved, while also critiquing the institutions responsible for the scarcity of material research that currently exists. MOTHA’s queer histories, or hirstories, are told through a queer and anti-establishment lens – exactly how trans history should be remembered. “I approach history in a really expansive way,” says Vargas tells AnOther. “I’m not pulling out facts or trying to create a master narrative, but trying to approach it in a different way than history is typically approached.”

It’s this kind of awareness surrounding the importance of how the histories are told and remembered which makes MOTHA such a valuable and worthwhile project for the trans community. (Side note: for a similarly important UK-based project see the Brighton’s Museum of Transology.) MOTHA’s position of transience – pun intended – was born out of what was almost a joke: MOTHA was initially an act of “creating this idea of an institution, and not necessarily doing anything except that”. A dry, critical humour runs throughout Vargas’ work: his first major collection was Trans Hirstory in 99 Objects, “a tongue in cheek engagement with the Smithsonian’s History of the US in 101 Objects,” which in turn took its name from the British Museum’s frankly absurd History of the World in 100 Objects.

For Vargas, institutions and everything associated with them should be approached with caution and a healthy scepticism: after all, most have historically excluded trans narratives and later only included them in minor degrees. MOTHA wants it to go beyond the standard narratives – the ones which peg Stonewall as a singular monumental event, that want to reduce decades of arrests, disobedience and resistance to one evening in one bar and one brick thrown by one person. “It’s usually not so focused, or not so singular, it’s more part of a movement and that story is harder to tell,” Vargas says.

In 1966, three years before Stonewall, riots broke out in Compton’s Cafeteria in San Francisco – the story is much the same as Stonewall, except the arrests were interrupted by a cup of coffee rather than a brick. Fuelled by frustration over constant harassment and incarceration, the action quickly escalated into thrown tables and chairs, before the spilling onto the street, the LGBT regulars smashing all the windows of a police car and igniting a newspaper stand. The current Oakland Museum exhibition features a nod to the riot in the form of mugs, which were bought from thrift shops in the Tenderloin area near Compton’s Cafeteria and redecorated by artist Nicki Green to commemorate the event. The inclusion of this story is important, if not purely for the fantastic image of angry trans women throwing cups of coffee at cops, for the broadening of trans narratives and, at least partially, the contextualisation of Stonewall within wider queer unrest, says Vargas: “It’s a bubbling up, it’s a ramping up – it’s in the zeitgeist, you know?”

Considering the current political climate and views around trans people and their identities, the work that Vargas is doing to establish an adequate history of our community, where mainstream institutions have failed, is invaluable. Heightened visibility combined with right-wing governments and ideologies in the UK and the US mean that this is a particularly dangerous moment for trans people in western cultures, especially those who are marginalised even within the trans community.

Vargas’ efforts to show the breadth and depth of trans history, to show it as more than canonised individuals and events, in a lot of ways legitimises our existence. In showing that we’ve been part of a widespread but predominantly undocumented and ignored history and situating the existing histories in context rather than isolation, Vargas connects our community to its very real and credible history, giving us a valid stake in this society and a right to be here. Our history might need to be uncovered and brought to us by people like Vargas, but it exists. As he says: “We’ve always been here. We’re not going anywhere, so, y’know, deal with it.”

Queer California: Untold Stories is at Oakland Museum of California until August 11, 2019.