In the latest instalment of her column, curator Antonia Marsh considers the aloof, mysterious figure that appears again and again in the work of Kenneth Bergfeld

In her new monthly column for AnOthermag.com, curator and director of Soft Opening, Antonia Marsh, considers the work of one contemporary artist.

The other evening, someone was visiting me at Soft Opening on Herald Street and on leaving asked me if I knew whether Project Native Informant was open. Around the corner from us in Bethnal Green (nowadays there are a few galleries keeping each other company on the block, thanks to the eponymous Maureen Paley), Project Native Informant recently moved from their former ex-garage space in Mayfair to a storefront, glass-fronted corner on Three Colts Lane. I tend to work late so this question was posed firmly after dark and I quipped in response that even if the gallery wasn’t open, you’d be able to see the show. With a storefront space in a tube station, I obviously have a thing for windows. Clear but strong, both physically present and absent, protective and powerful markers of territory, windows decide where inside ends and outside begins and can render galleries uncharacteristically welcoming, democratising the viewing experience.

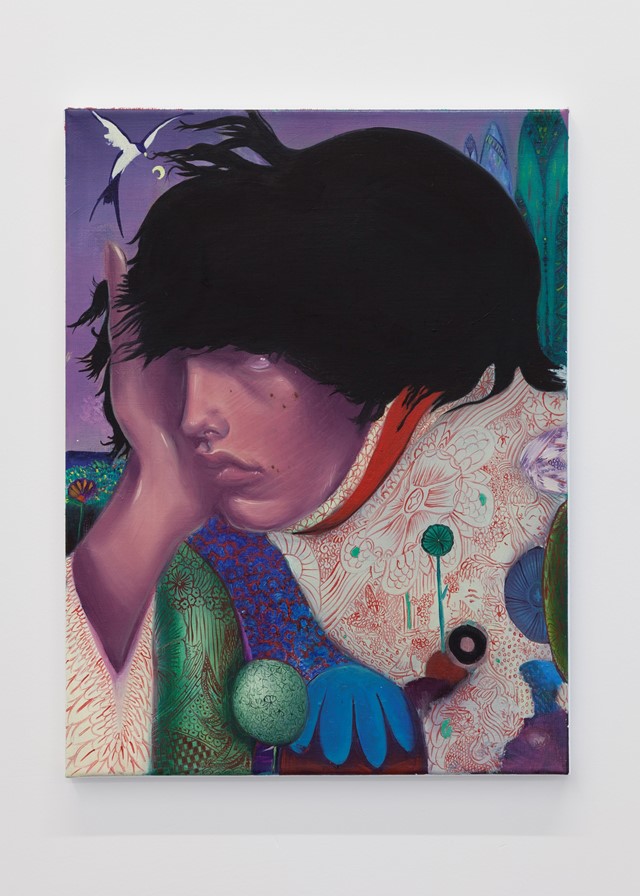

At both exhibitions prior to his current solo show at Project Native Informant, Cologne-based German painter Kenneth Bergfeld presented paintings fixed onto the inside window of each gallery. Hiding shyly from an external viewer, these paintings both depict a figure with an averted gaze and impressive, sculptural hair. In a night time installation image of What would you pay for a rotting whale, at Max Mayer, Düsseldorf in 2015, the reflection of the glowing sign for a hotel provides the backdrop for Bergfeld’s Dutch Mistress (2013). Spatial and temporal depth both feel flattened as the dark Düsseldorf exterior interacts with the pastel daylight in the work. At his exhibition The Spire (Part 2) in 2018, the artist’s Androgynous Angel VI (2018), a painting hung on the glass window at Part One in Cologne, similarly engages with its environment. A trippy Arcadian scene floats off the figure’s clothing and into the background, as the boughs of trees in a local park surround the work in soft green.

At Project Native Informant, Bergfeld presents I, Spider, the artist’s first solo exhibition in London. While no paintings sit directly on the gallery windows, every work is visible from the street. 12 paintings, limited to just two sizes, illustrate a continuing project to revisit the same portrait. Since his first Androgynous Angel (2015), Bergfeld has been examining this figure, with their hidden eyes, full lips, slick bouffant hair (although hairstyle does vary momentarily in the newest work) and colourful backgrounds that seem to perfectly match the mood of Bergfeld’s imagined subject. Sometimes quaint, sometimes camp, sometimes sinister: these backgrounds are either loaded with decorative detail or kept in block colour, which undermines any momentary certainty that they function usefully as indexical signifiers of deeper meanings within the inner psyche of the figure. Perhaps instead, these backgrounds enable a means to a formal end, space to investigate two-dimensional spatial organisation or even painting itself.

Oozing retrofuturism, the figure in Bergfeld’s larger canvases ignores or retracts from the picture plane, while in the smaller busts they seem to nonchalantly lean into our personal space. Vibrant, uncomfortably unusual hues and shiny, plastic textures suspend the paintings in an animated space of non-reality. This mysterious figure, not so much confrontational as aloof, perpetuates an inner inaccessibility through a glossy exterior veneer. But why repeat this one figure? Besides painting, Bergfeld works in music and animation film, both disciplines that engage with activities of repetition. In an interview with Christina Irrgang, Bergfeld explains that “repetition creates ‘cracks’ in our everyday lives and is a form of change in itself”. Repetition constitutes a marker of change and progress, of time passing between identical actions. By repeating this single figure, Bergfeld tracks the change in himself as he moves through time. “I didn’t want to solidify my identity as a young artist, but instead sought out the immersion into Androgynous Angel and locate myself through painting views of Androgynous Angel. I felt like committing to Androgynous Angel, not as a painting, but as a person.” Extending this assertion in her essay Scrambled Aches, Jessica Gispert writes “Kenneth Bergfeld’s Androgynous Angel series depicts an array of characters portraying fragments of his subconscious… One could even say these figures represent Bergfeld himself… The artist existing inside of his paintings.” Approaching this figure from multiple perspectives, whether pictorial or psychological, seems to allow the artist to navigate and examine a more complex understanding of himself.

A few days after my conversation with the gallery visitor, I was again leaving late and wanted to see the paintings at I, Spider again. This time the gallery was closed and it was dark outside, so I could just about make out the work. Bergfeld’s angels loomed spookily in the darkness, staggering into the space before me, only separated by the windows. Not dissimilar the interaction between painted surface and glass at the shows in Düsseldorf and Cologne, at Project Native Informant, the window marks not only the break between interior and exterior, but between embodied and virtual identity, between reality and fantasy.

Kenneth Bergfeld, I, Spider was at Project Native Informant, London until May 18, 2019.