Kohei Yoshiyuki’s 1970s series The Park explored voyeuristic exchanges happening at night in Tokyo’s public parks. 40 years later, and the series is now being republished as a photography book

Kohei Yoshiyuki’s pictures of late-night antics in Tokyo parks caused consternation when they were first exhibited in 1979. “A lot of people made a lot of noise about them,” said Nobuyoshi Araki in an interview with Yoshiyuki in 1980. “My critique consisted of exactly one line: ‘These are what I call photographs.’”

Deeply strange, utterly compelling, grotesque, funny and, at times, quite frightening, the pictures in The Park explore a flourishing urban underworld that conservative 1970s Japanese society was not fully prepared to face. Through his lens, Yoshiyuki demonstrated how Tokyo’s socially ordered leisure spaces were transformed after dark, subverted into anarchic realms where people came together to satiate their individual desires. Now, the series is being republished as a photography book, featuring previously unpublished images, an essay on the series by photography critic Vince Aletti, and the 1980 conversation between Yoshiyuki and Araki.

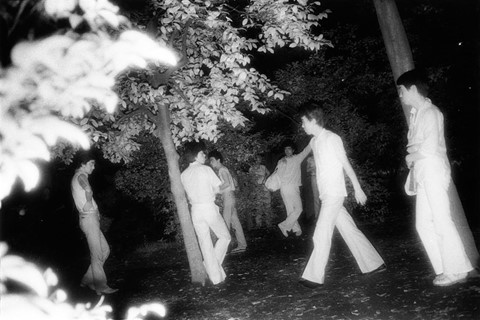

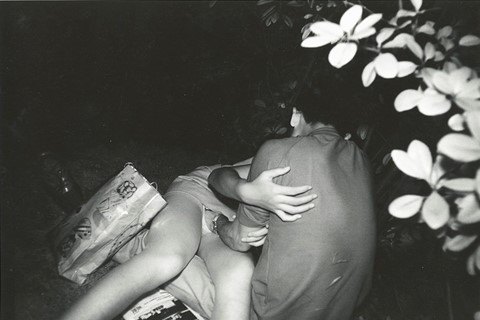

The Park is about the many faces of desire, starting with the couples in frenzied tangles in the bushes, moving out to include the voyeurs who lie in wait in the dark, drawing closer, pulling aside branches, even clothes, to get a better look. These are the peepers, men who loitered by the park entrances watching and waiting. To take his shots, Yoshiyuki joined their ranks, his shadow mingling with theirs, learning to identify likely amorous pairs. “Only couples who have had sex before fuck in a park,” the photographer, who is now in his seventies, told Araki. “You can always spot them because they walk fast.”

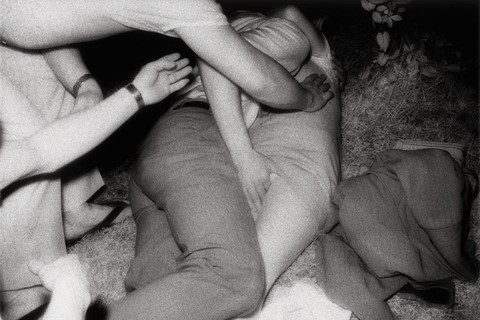

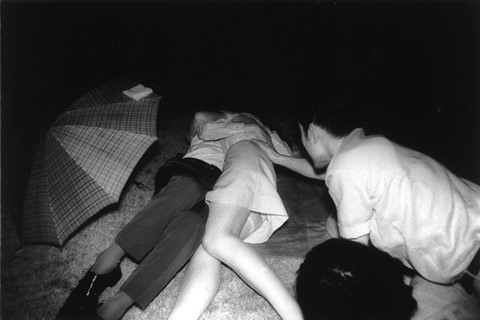

His tiny camera, fitted with an infrared bulb, went off with a red flash – “like the lights on a passing car,” says Araki – so his subjects rarely knew they were being photographed. But perhaps this obliviousness is better attributed to the voyeurs’ intense focus on the matter at hand. While in the darkness each one was enjoying a largely solitary experience, the camera flash reveals near-comically crowded scenes, clusters of men leaning, crawling, straining for a better look, some even daring to reach hands into the melee of limbs.

There is a troubling edge to Yoshiyuki’s pictures – these are photographs of people having sex, after all, taken without their knowledge or consent – yet somehow they are not prurient. The photographer’s eye is fixed on those who are watching, the men in pale trousers, holding tote bags and with their flies unzipped, their eyes gleaming white with excitement at other people’s passion. Those stretching hands imply a desire for contact and intimacy, yet the peeper’s contract requires that each man must stay silent or risk discovery. The Park exposes this strange paradox, multiple men attempting to hold their excitement in check for fear of being caught. Palpable too is the threat of what will happen should the tension bubble over. What if the mob of men can’t control themselves? What if the contract breaks and the peeper intervenes? Writhing in the dirt, the couples are in a dangerous position. “In their place,” said Yoshiyuki, “I’d be scared.”

The Park created a sensation when it was first shown in Tokyo in 1979. Yoshiyuki egged on his scandalised audience by forcibly enlisting them into his army of voyeurs through the exhibition’s hanging. “I blew the photos up to life size. That way I was reconstructing the original settings,” he recalled. “I turned out all the lights in the space and gave each visitor a flashlight. Since the points of light were also their lines of sight, I saw things that were totally unexpected.” This was something unexpected for his audience too, forcing them face-to-face with the realities of a culture driven by isolation and desperation, realities shielded from the light of day by strictly conservative norms and the anonymity provided by fast-growing urban sprawl.

40 years on, the images in The Park have lost none of their power to shock and transfix; indeed, viewing them in the Instagram-addled age prompts new questions about surveillance and personal privacy, the need to actively police the ever-blurring line we draw between what we share and what we keep secret.

“Lechers are the only hope for the 21st century,” Araki tells Yoshiyuki in 1980. “Only lechers come up with good ideas. Only lechers take good photos. So are you one, too?”

“I think I’m completely ordinary,” replies Yoshiyuki, “but I think there is a bit of lecher in everyone.”

The Park by Kohei Yoshiyuki is out now, published by Yossi Milo Gallery and Radius Books.