A new exhibition of Erwin Blumenfeld’s non-commercial nude studies, entitled Chasing Dreams, explores his mastery of illusion through the female form

Erwin Blumenfeld is best known for his contribution to fashion photography, a genre he elevated to an art form while working for the likes of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar in 1940s and 50s New York. His visionary, highly experimental approach drew on the work of the Dadaists, the Surrealists and similarly pioneering photographers such as Man Ray, which he encountered while living in Europe – first in his native Berlin, then Amsterdam, then Paris, before the Nazi occupation forced him to flee to New York in 1941. It was cultivated through a vast body of personal, non-commercial work, which is both just as worthy of attention as Blumenfeld’s fashion photography and intrinsically linked to it.

“Blumenfeld is the most fascinating artist,” explains celebrated gallerist and collector Howard Greenberg, speaking at the opening of Chasing Dreams: Experimental Nudes 1936–1955, a new exhibition of the photographer’s work – much of which is on loan from Greenberg’s New York gallery – at Chaussee 36 in Berlin. “He’s first and foremost a Dadaist, a radical, making very political, very excellent art. But, like many other photographers, he needs to make a living so he evolves his style for magazine and fashion work, bringing with him the sensibility of the various art movements that inspired him. He could do that because he was brilliant and different and knew how to make it work.”

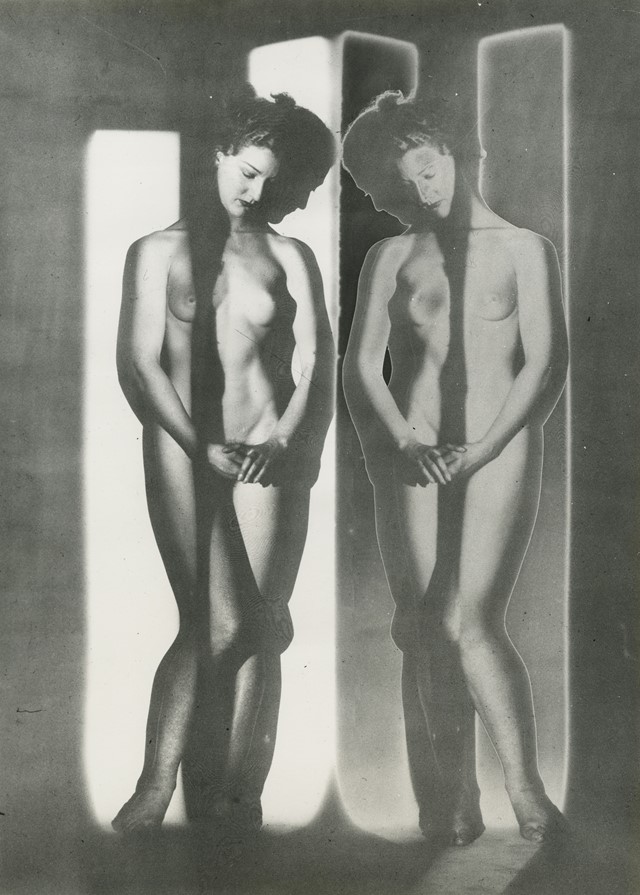

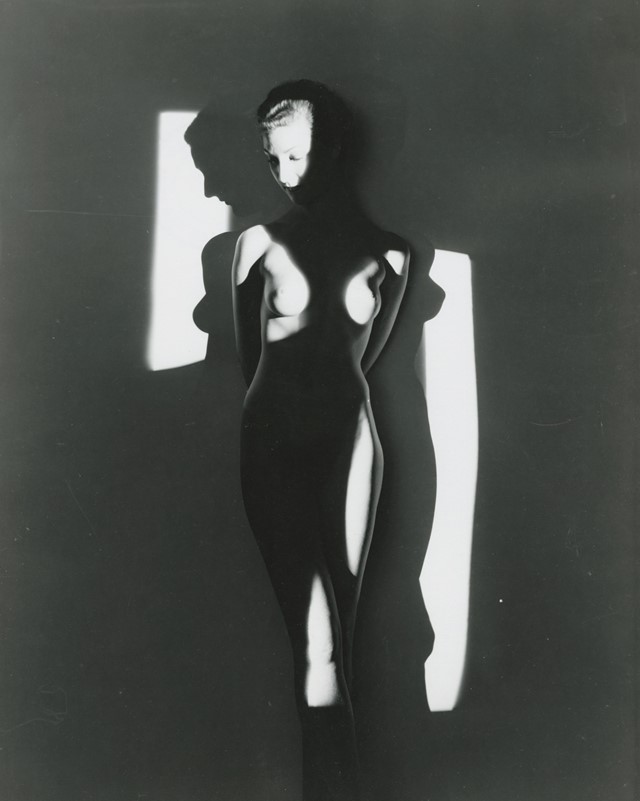

Blumenfeld had two principal obsessions: the desire to innovate and the female form. This exhibition, as its title suggests, explores both of these “eternal chases” through around 40 nude studies, made in Paris and New York, which, even to a modern viewer, are breathtaking in their technical wizardry and poetic, dream-like rendering. “You often can’t understand how he made these pictures because his imagination was so fertile and his ability to use the materials at hand, both in the studio and in the darkroom, was so advanced,” Greenberg says, gesturing at a wall of photographs where Blumenfeld’s use of mirror images, shadows and solarisation have transformed nude bodies into quixotic, Cubist apparitions. (In one, the clever exploitation of light and shade has cast violin-shaped shadows on the model’s body in direct homage to Picasso’s Cubist works.)

Many of the works use multiple exposures or strategically placed mirrors to warp and replicate their subject – to captivating, illusory effect. “I’ve never had time for realities, I was always entangled in illusions,” the photographer once said. Other images on display confirm Blumenfeld as a master of visual manipulation: close-up crops of the female form display delicate patterns of light and shadow; the use of diaphanous fabrics shroud his subjects behind otherworldly veils; negative “sandwiching” (where two negatives are placed together before processing) creates chequered or circular grid overlays that serve to highlight the intricacies and mysteries of the human form.

“It’s obvious that Blumenfeld loved women, but he really used the female body as a model, as a form, to generate ideas,” Greenberg observes. It is easy then to understand Blumenfeld’s smooth transition into the world of fashion, where his singular approach to the representation of the female form (think: his famous, 1950 “Doe Eye” Vogue cover which used light to reduce Jean Patchett’s face to her eye, mouth and beauty spot) would open the door for artistic expression in fashion photography in a way never dreamed of before.

Chasing Dream: Experimental Nudes 1936–1955, curated by Alice Le Campion, is at Chaussee 36, Berlin until November 30, 2019.