In 1981 Gary Schneider made a short film about exhibitionism, featuring Peter Hujar and other friends. 38 years later, he has released it as a compelling book of portraits, published by Dashwood Books

In the summer of 1981, South African photographer and artist Gary Schneider and his partner John Erdman did what they’d done for the past three summers and vacated their home in New York City for a seaside holiday cottage on Long Island. The rental house formed part of Salters Cottages, “a very small, discreet community [whose inhabitants] spent much energy staying out of each other’s way,” Schneider explains. Like other years, the artist invited his friend and mentor, the visionary photographer Peter Hujar, to come and stay in the cottage’s spare room. Unlike previous years, however, Schneider decided that that summer, he would make a short, experimental film, featuring Erdman and Hujar and two other artist friends, Suzanne Joelson and Gary Stephan, who were vacationing close by.

“I had completed two films previously,” Schneider tells AnOther. “I was interested in avant-garde art films, from the Surrealists to that present; in fractured narrative and the portrait – in my case, performance always plays a critical role.” He was, he explains, particularly inspired by Jean Genet’s short queer film, Un Chant d’Amour (1950), which revealed to him the potential for fragmented storytelling “where there was a constant shift in point of view, despite there being one key protagonist”.

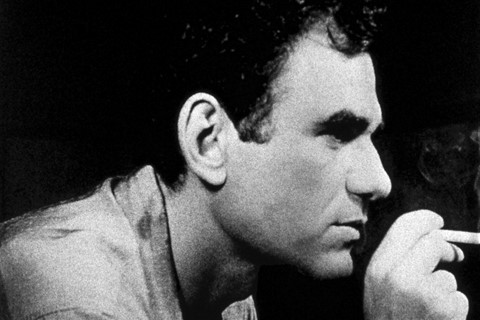

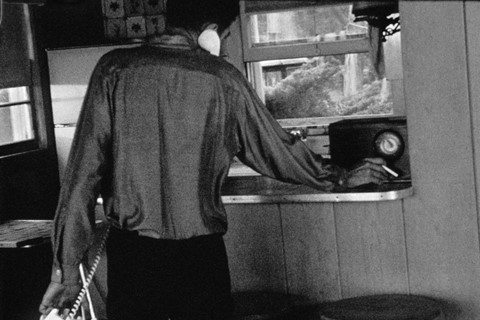

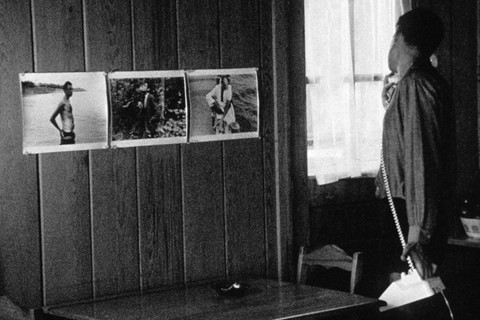

The resulting 15-and-a-half-minute film, Salters Cottages, is the story of a group of exhibitionists, which explores the exhibitionist desire to be observed and the therefore-debatable voyeurism of the observer – a theme also borrowed from Genet. Nudity, spying and smoking (which Schneider describes as the film’s “means of communication”) abound, stylishly captured on 16mm film and set to a Bell and Howell projector soundtrack.

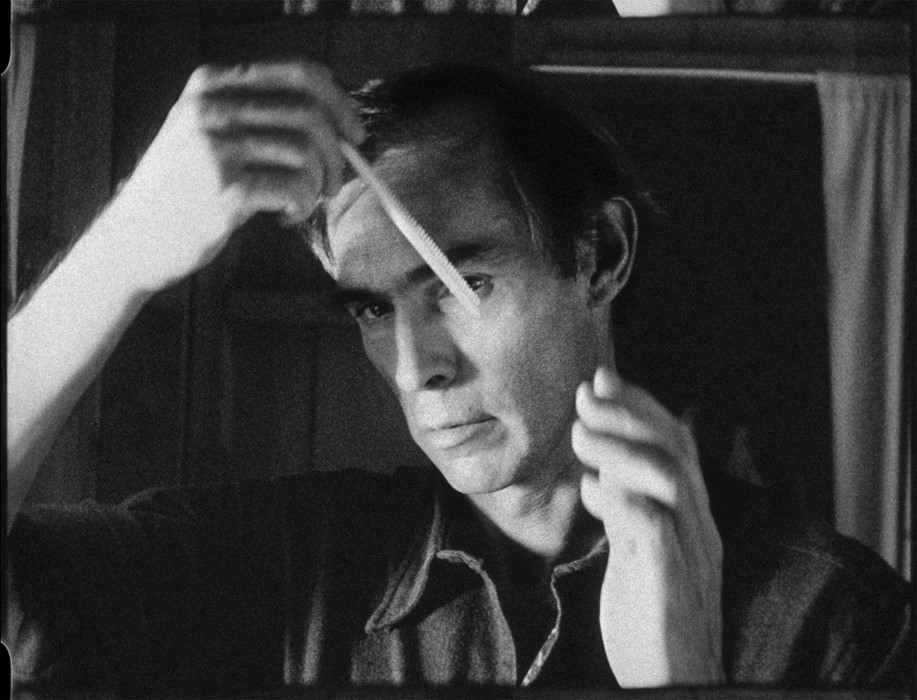

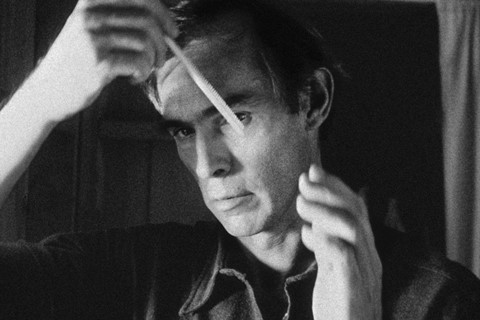

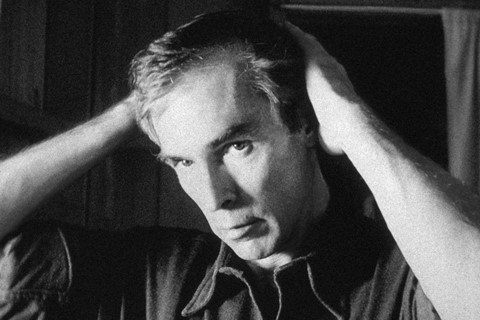

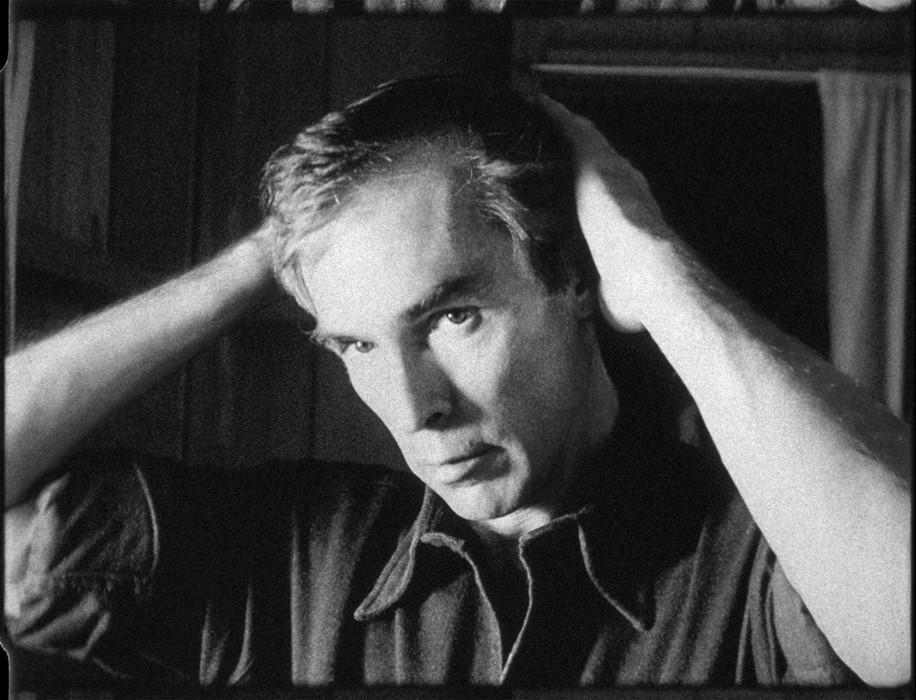

Now, some 38 years after its realisation, Schneider – who has since garnered much acclaim for his bold, scientific advances in photography and portraiture-making – has compiled a photobook made up of select stills from the film, which proves an equally compelling artwork in its own right. There is a noir quality to the images when no longer in motion, while the freeze framing of each character gives the viewer the opportunity to study them more closely: Joelson looks every part the Hitchcockian heroine, sitting in a darkened room, smoking, lost in thought; a pale peeper blurs eerily with the sunlit window through which he spies; Hujar combs his hair while gazing out of the frame, as if we the viewer are watching him covertly through a mirror.

“The book evolved to be very different from the film over the four years I worked on it,” Schneider explains. “Peter died in 1987 and my ten years of knowing him, and his influence on me, has remained with me. His sequences have more presence in the book than the film. I also simplified the fractured narrative to make the book more about temporal portraits. Performance, in contrast to acting, is about what the person brings of themselves and this aspect is foregrounded here. My favorite memory from the project is the engagement with my friends – I am certainly grateful to them for bringing such singular performances.”

Salters Cottages is out now, published by Dashwood Books.