When, back in 2012, I found myself sitting in the Dorchester hotel one evening with Kevin Systrom, who was lolling deep in a whiskey-drinking competition with Jack White (really!), I didn’t realise quite how important Mr Systrom was. Instagram, the app he’d created with Mike Krieger, had launched a couple of years before. I remember knowing he’d just sold it to Facebook, and liking the kitsch-y feeling of its square format and filters, but I also remember that I preferred taking pictures with my Pentax and kind of thought that was that...

In the decade that followed Instagram’s launch, it has transformed the way we see ourselves and the way we communicate. Martin Parr’s recent photo book Death By Selfie reveals (with Parr’s typically wry eye) the lengths we’ll go to create photographic evidence of our daily lives that we can share with an unlimited digital audience. Instagram arguably forged the ‘attention economy’ that now dominates our culture wherein human behaviour – and the data that tracks it – is the most valuable resource on Earth.

Selfie culture constrains us, demanding we filter not just our images but our lives, so that they appear perfect – successful, pleasurable and beautiful. But it’s also open enough to allow braver voices to express non-conformist, radical perspectives, acting as a space in which self-determination is more democratic. Photography has always been a medium wherein identity is controlled, forged and remade, but social media provides a platform that makes the rebellious margins of identity construction more visible – and therefore powerful – than ever. This democratisation has influenced photographic practice more widely, and in the last ten years, BAME and LGBTQ artists have made some of the most significant work.

Chinese photographer Ren Hang (1987-2017) depicted a kind of Edenic pop land in his photographs, full of naked bodies, lush vegetation, beguiling snakes, painted nails, cars and cigarettes (these last two commodities were tropes for freedom in late 20th-century America, which feels relevant). His work is erotic, insouciant and liberated. The series of pictures he made of his partner Huang Jiaqi, which he published in book form in 2013, is a paean to queer desire and a seditious act directed against a constrictive Chinese regime.

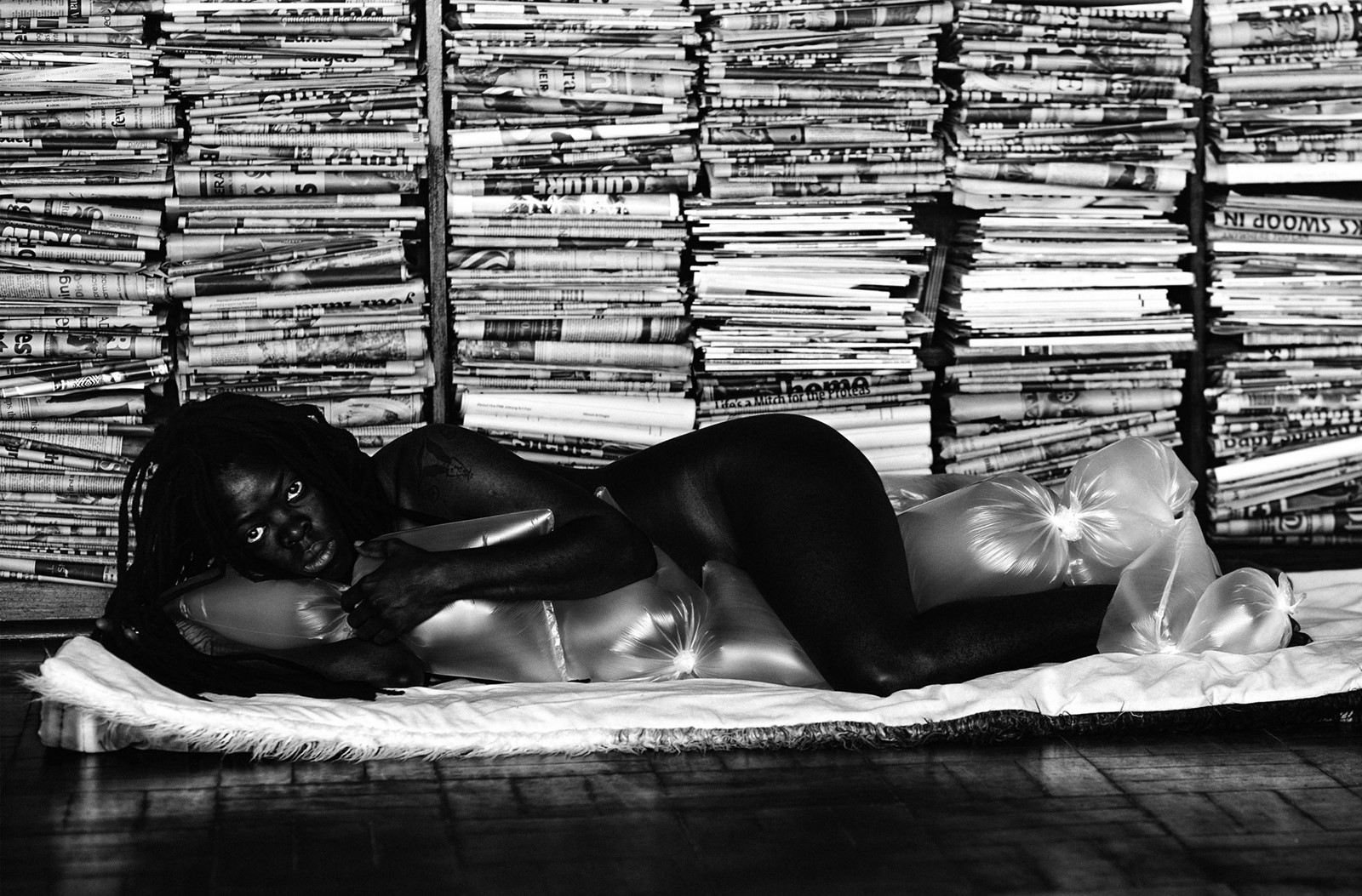

The work of South African image activist Zanele Muholi is likewise fearless in the face of discriminatory, dominant political power. Muholi recognises photography as an arbiter of beauty, taste and value that is too often in the same hands, creating hierarchies that exclude people of colour as well as the LGBTQ community. They work to make visible their experience in self-portraits that recall and reposition the tropes of African beauty as well as their own specific history. They also make portraits of black lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex South Africans who have suffered persecution despite the country’s 1996 Constitution (which prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation).

The last ten years have seen a new generation of women photographers exploring ‘the female gaze’ and asking whether they can resist objectification by stepping behind the camera themselves. I’m not sure if this strategy is always successful (John Berger’s assertion that “the surveyor of woman in herself is male” feels, disappointingly, still true). But Collier Schorr, Laia Abril, Harley Weir and Carmen Winant have all, I think, escaped this trap. Schorr’s move into fashion photography (from the art world) signalled her appreciation of its reach and power, and I love her approach because instead of trying to strip the image of desire, she complicates and radicalises it (maybe this is what David Sims does, too, but for the 21st-century male psyche, itself vulnerable to conformist pressures). Laia Abril’s meticulous, research-based work is uncompromising in its demonstration of the subjugation of women in the 21st century. Harley Weir’s book Function (2018) explored the biological functionality of the female body, its status as a vehicle for desire, and the link between the two (see my interview with model Jess Maybury for more on this!). Artist Carmen Winant’s My Birth (2018), which collated hundreds of photographs of both her own birth and those of other women into a collaged installation, was recently exhibited at MoMA in New York. It explores an event that is both a major female experience and one of the most powerful female acts, but which is still largely masked, conceptualised and administered by patriarchal forces.

The rise of digital imagery has a darker side: surveillance. Marisa Bellani, director of leading London gallery Roman Road, reminded me that, in London, the last decade was ushered in (in 2010) by a photography show at Tate Modern called Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance and the Camera – the first curated by Simon Baker, then the new curator of photography at Tate. At the decade’s close, artist Oliver Chanarin observes that “computers and intelligent AI algorithms and devices implanted in our daily lives are generating photographs all the time and those photographs are generally not for us to look at but for machines to look at. There are now more photographs produced by machines for machines, than by humans for humans.” Photographs of us taken without our consent proliferate secretly, all the time and everywhere. Artists Jon Rafman and James Bridle have addressed this in recent years, and Chanarin’s new work THE APPARATUS (2019), which will be shown at Plattegrond Meterhuisje in Amsterdam next year and at SFMOMA in 2021, does so too. Irish photographer Richard Mosse’s three-channel video installation Incoming (2014-17) documented refugees as they endured the passage from Africa and the Middle East into Europe using military surveillance technology that allows images to be captured from a significant distance. It raised important questions about the ethics of image-making and the nature of documentary in the 21st century.

One of the best things I heard this decade was stylist Lotta Volkova’s statement, “There are no subcultures anymore. It’s about the remix.” The possibilities for ‘underground’ creativity and expression have diminished as commercial powers have become intelligent enough to invite newness into the fold very quickly. The borders between genres – art photography, fashion photography, commercial photography – have also been crossed with much more frequency. And I love so much of what has happened as a consequence! How brilliant was Pieter Hugo’s project with Hood By Air, Martin Parr’s photographs for Gucci’s recent beauty campaign, Heji Shin’s real-sex campaign for Eckhaus Latta or Tyrone Lebon’s work for Stüssy and Bottega Veneta? I see them all as post-Warholian affirmations of the power of commercial imagery, and anyway, I have a theory that the best art directors of our time are just artists in disguise (if Richard Prince had been born in 1979, not 1949, he’d probably be on the books at Art Partner). The movement into commerce has been so much more interesting than the movement away from it – the desire of fashion photographers to become ‘artists’ almost always feels as if it rests on the mistaken idea that the art world is a utopian space free from the forces of market, politics or censorship and that it’s therefore more ‘important’.

As digital photography turned everyone into an amateur photographer over the last ten years, there was a return to analogue and a new obsession with process amongst those who chose photography as their vocation. Bellani suggests: “The decade really opened and grew around printing techniques and experimentation, all the students went back to the darkroom – that became art again, because it was so easy to print digitally. People like Thomas Mailaender, Antony Cairns, Daisuke Yokota – all those guys were asking, ‘how do I make something relevant now, without just sending the file to a lab to print it?’ They were really trying to push the boundaries of what you can do to achieve a print, it was not about image-making other than gathering an archive to work with. So, we broke completely with the idea that the photograph is representational.”

An obsession with archives also shaped the photographic landscape of the 2010s, suggests Bellani, which makes sense in a world of endless data, where the act of choosing – and choosing well – feels precious. This is why the word ‘curation’ has entered the mainstream...

How will the next decade of photography unfold? I wonder whether we’ll grasp the terrifying implications of how data is shared via images, and try and do something about it. I wonder if a more nuanced, sophisticated and ultimately healthier relationship with desire will emerge from the ashes of #MeToo (and in the face of internet pornography). I wonder if our love of photography from a pre-digital time will endure (Don McCullin’s recent exhibition at Tate Britain vastly exceeded its visitor targets). I hope the answer to all these questions is yes.