Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, hosts the first comprehensive exhibition dedicated to Andy Warhol’s photography from 1967 to 1987

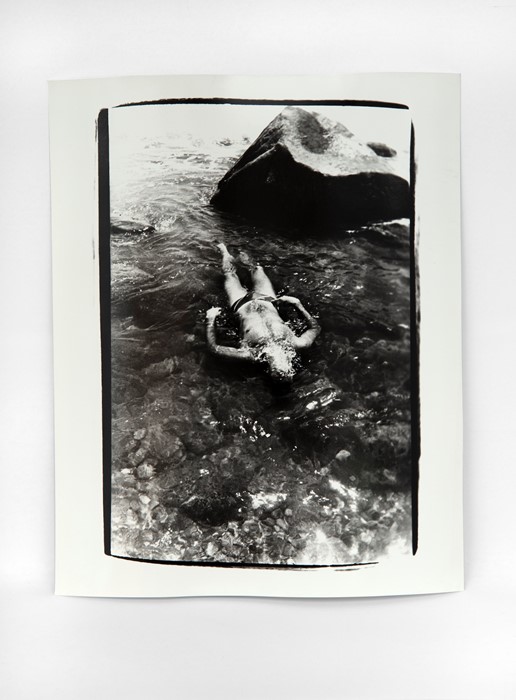

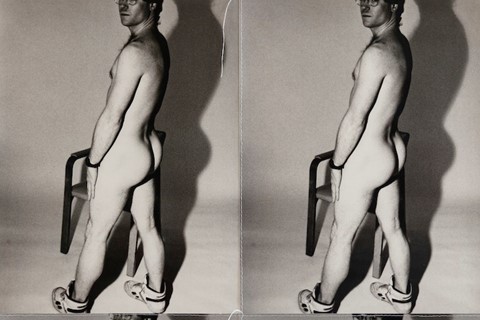

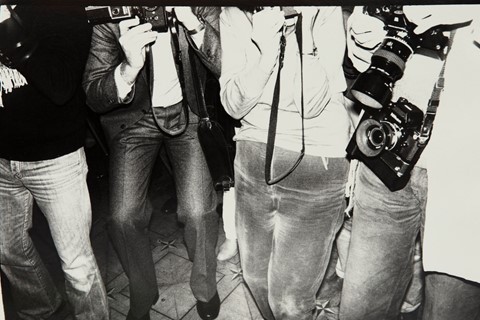

Andy Warhol often referred to the camera as his “date”, taking it with him to countless social functions from the late 1960s until his death in 1987. The camera gave him the ability to be in the middle of the action, watching others shamelessly, while simultaneously providing a barrier between himself and the world.

“It is interesting to think about the camera as a middle ground that helped Warhol navigate the public sphere while maintaining a bit of privacy,” says gallerist Jack Shainman, who is currently showing Andy Warhol Photography: 1967–1987, the first comprehensive exhibition of the artist’s photographic practice.

Photography played a large role in Warhol’s life, beginning in his childhood. A Kodak Brownie camera was one of the earlier luxury items the family owned, while his brother John ran a photo shop with a photo booth. Young Andy avidly collected Hollywood fan photographs, their timeless glamour informing his own work.

Warhol launched his fine art career using pre-existing photographs of celebrities like Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, and Elizabeth Taylor to make a series of silkscreens that took the world by storm. “In an era where the Abstract Expressionists ruled, Warhol strived to reflect his interest in the pervasion of commodity into everyday life,” Shainman says.

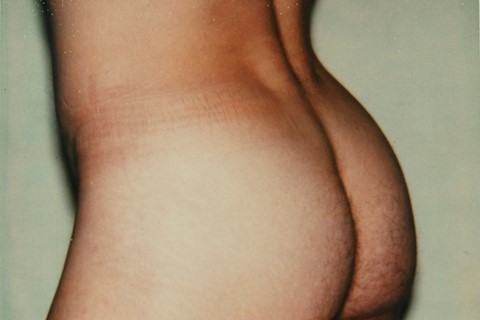

By 1971, the demand for commissioned canvases was such that Warhol began using a Polaroid camera in 1971 to make portraits himself. “He wanted to capture his subjects at their best and really tailor the image, so the ability to be heavily involved in the image making process allowed him get exactly what he was looking for,” Shainman says.

Five years later, the camera had become a vehicle for Warhol to create a visual diary of his life. Driven to document the chic and the banal with equal aplomb, Warhol would photograph everything from street signs to table settings at the end of a meal.

“There is a quote in which Warhol mentions enjoying photographing leftovers and discarded things because everyone understood that they were unwanted,” Shainman says. “This speaks to the nature of his later photographs. They went beyond the facade and captured a more intimate and holistic reality.”

In 1977, his Swiss Dealer Thomas Ammann presented Warhol with a 35 millimetre Minox camera, which he would use to create 130,000 photographs. By the time of Warhol’s death, only 17 per cent of those images had been printed. The 193 pictures now on view, rarely – if ever – seen before, offer an insight into Warhol’s deepest instinct: the ever-present eye, always searching for pure Pop energy.

Andy Warhol Photography: 1967–1987 is on view at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York until February 15, 2020.