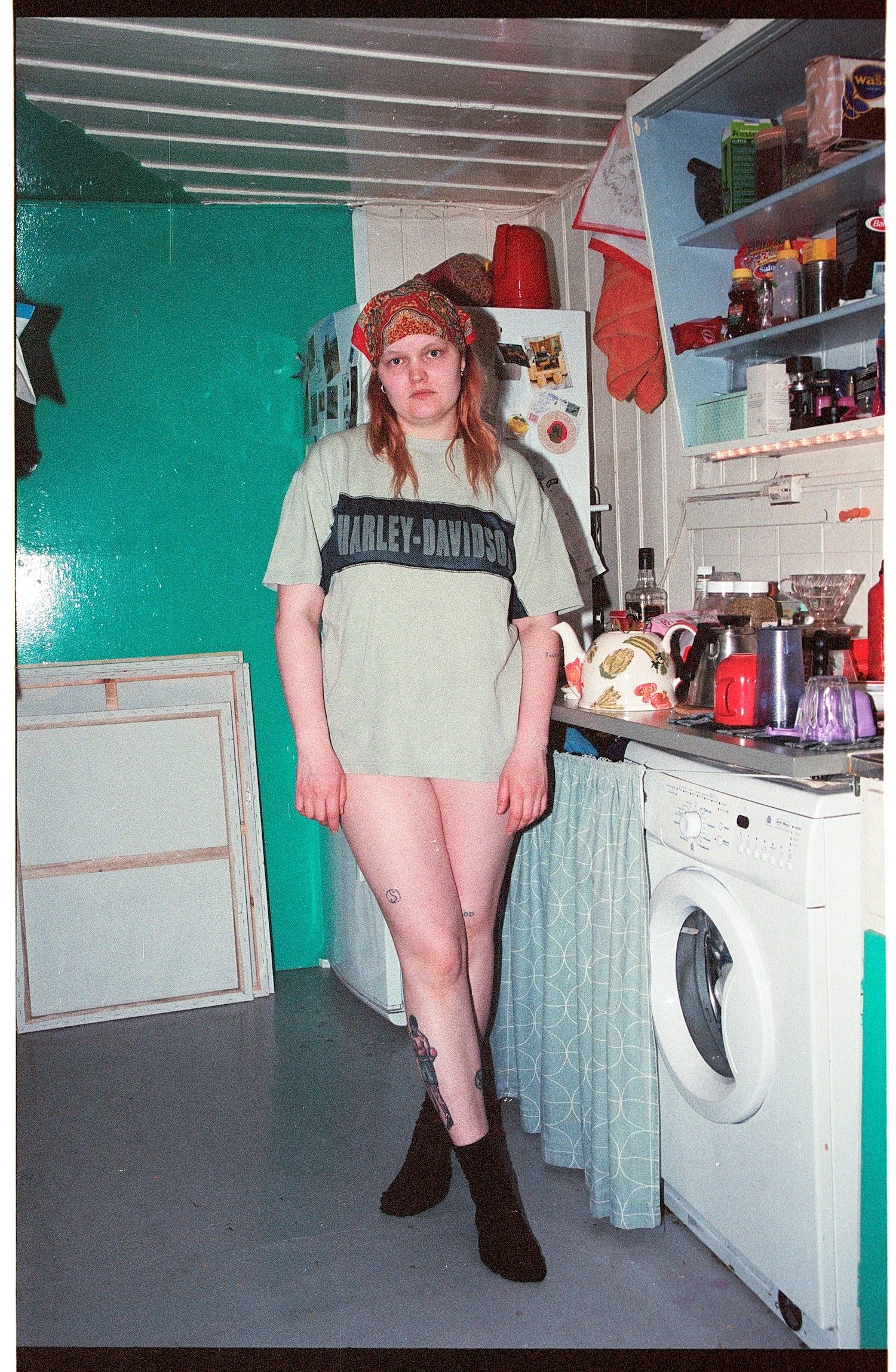

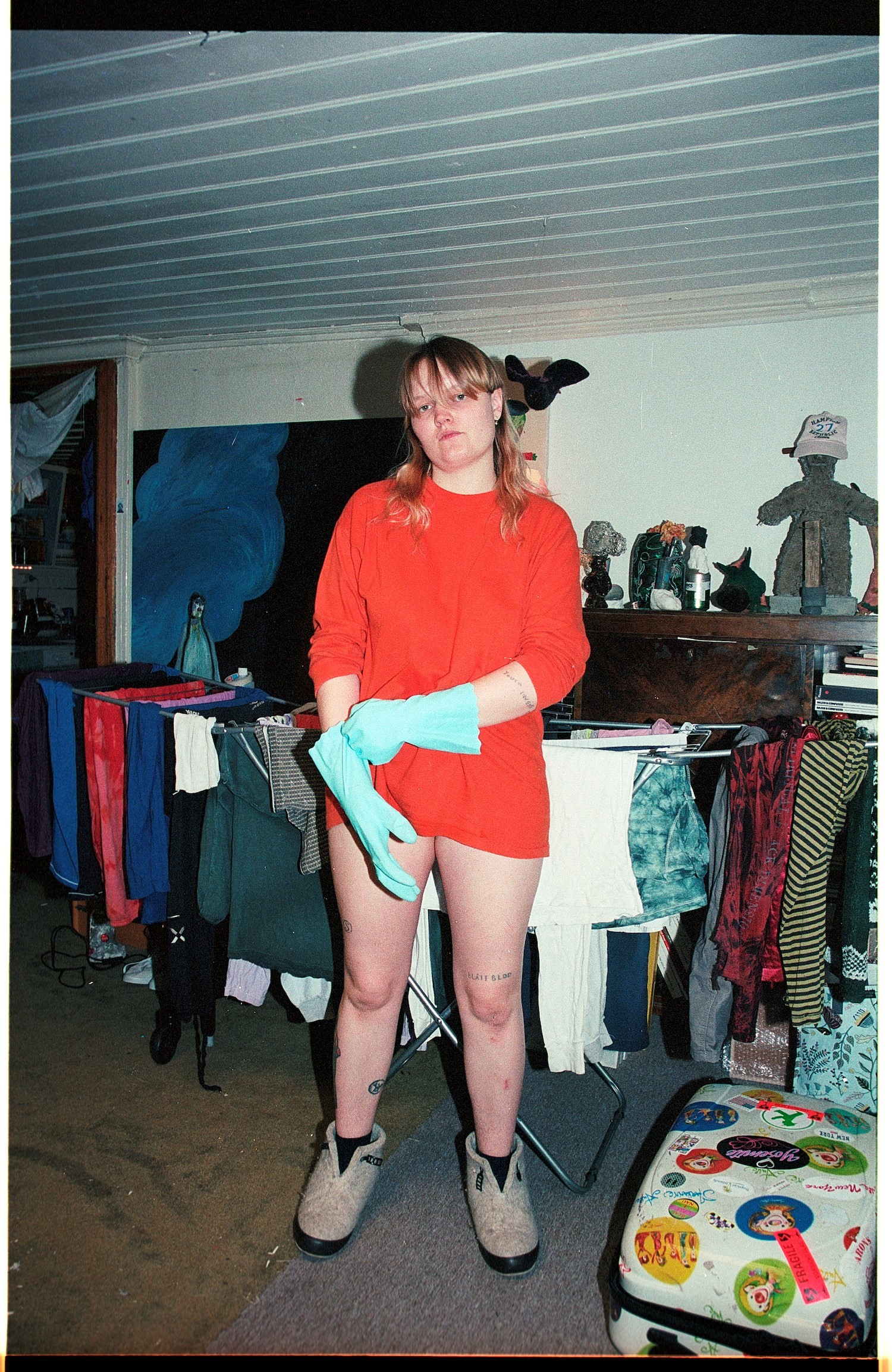

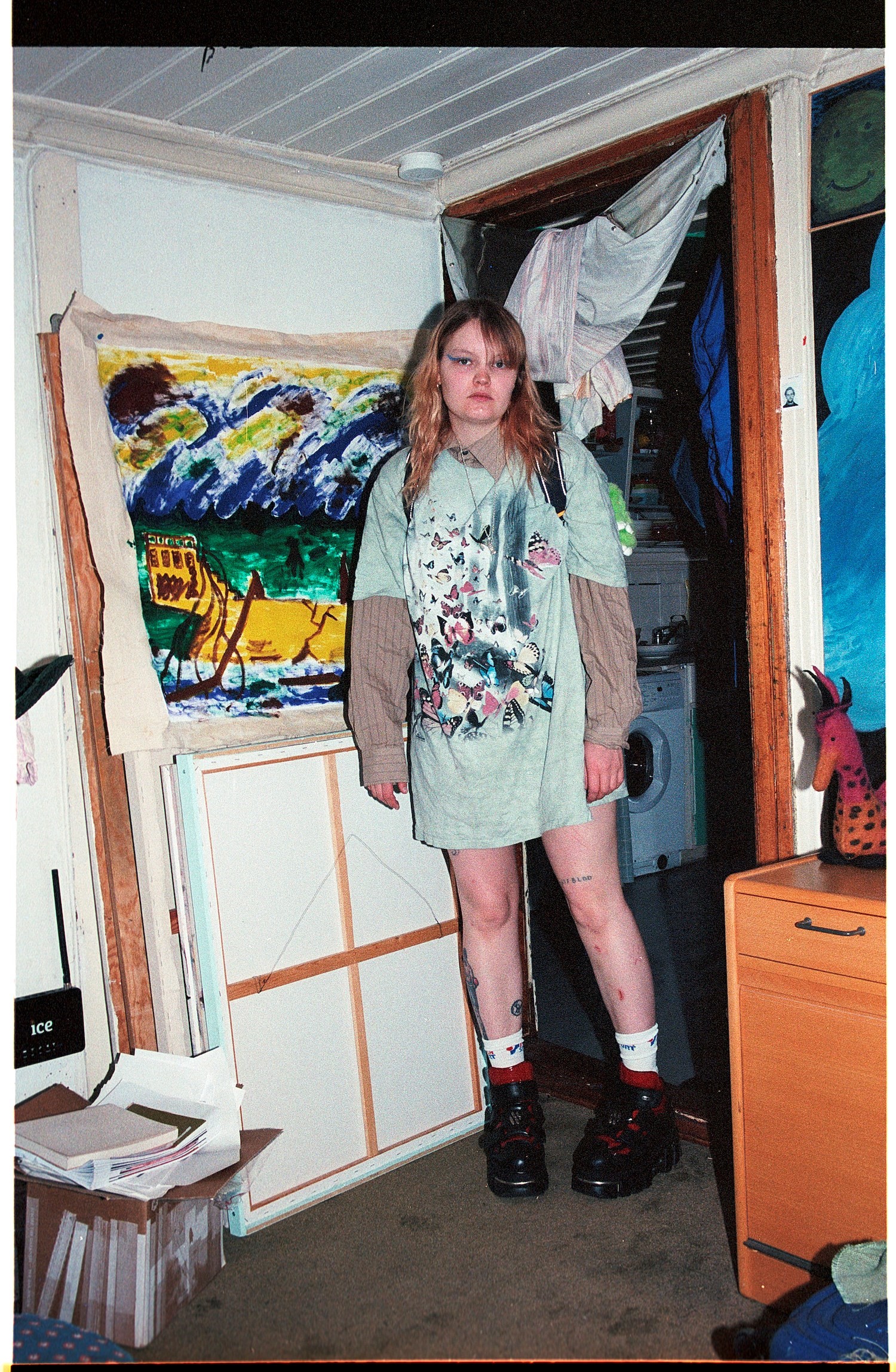

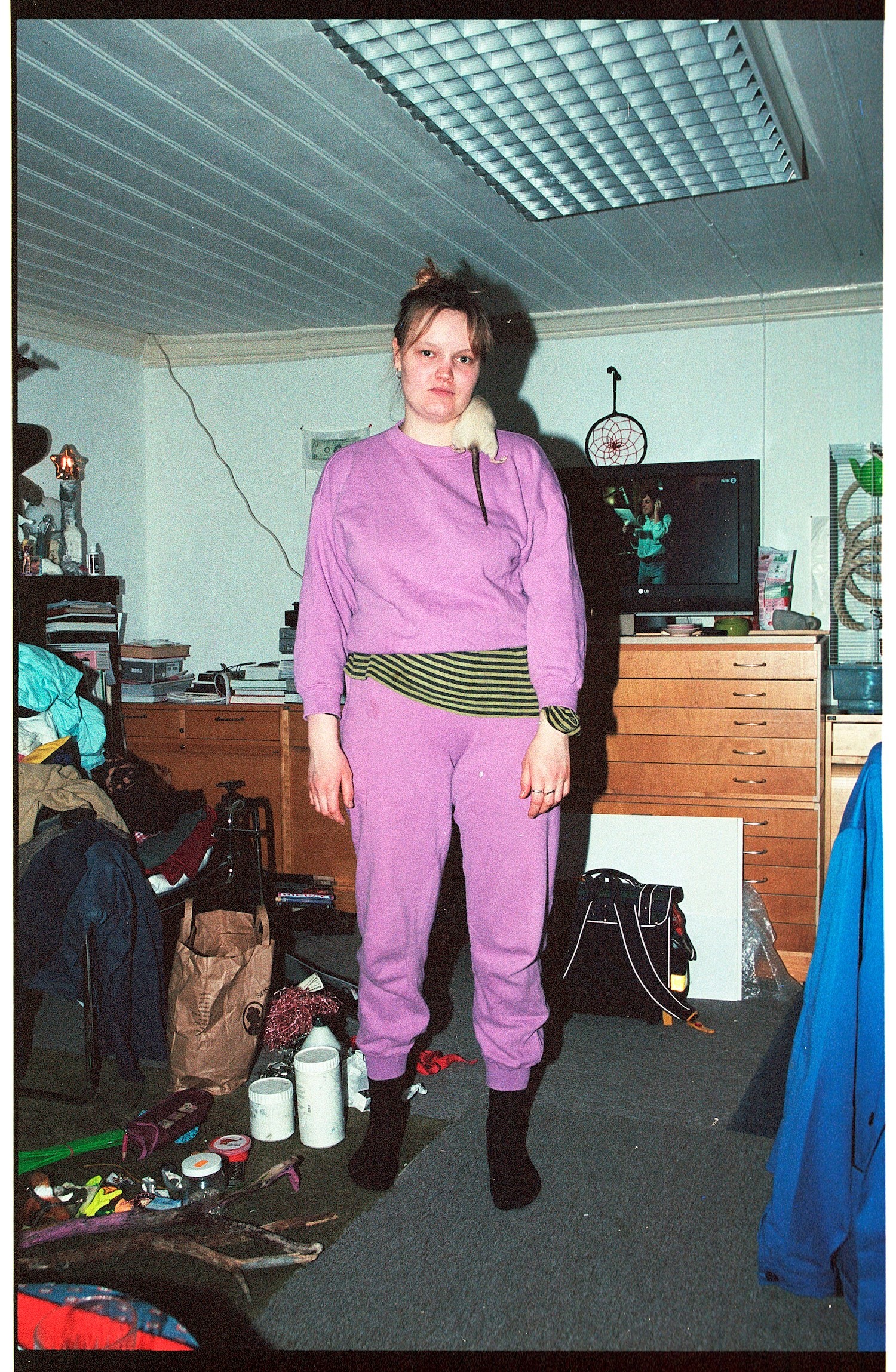

Maria Pasenau’s first photo book, Whit Kind Regards Pasenau, is a diary-like compilation of pictures the Oslo-based image-maker captured of her and her friends’ lives. Pasenau self-published the book in 2018, the photos a document of her early twenties in a new city. Day to Day is Pasenau’s newest series, and focuses entirely on herself: the artist decided to take a self-portrait every day for a year, from October 11, 2018 until the same day in 2019. Wherever she was – mostly in her apartment in Oslo, but sometimes in London or Berlin – and with the help of alarm reminders on her phone, Pasenau would capture herself, no matter her mood.

We see Pasenau in varying outfits, settings and states of emotion throughout the 365 images, which are now on show at Antonia Marsh’s subterranean gallery Soft Opening in an exhibition curated by Dazed’s editor-in-chief Isabella Burley. 365 Days of Pasenau shows the year-long project on a screen, the images changing every two seconds, alongside a sculpture by the artist, filling a section of Soft Opening’s storefront vitrine space in Piccadilly Circus tube station. Here, as 365 Days of Pasenau opens, we speak to Pasenau and Burley about the uniquely intimate series.

Belle Hutton: How did the series first come about?

Maria Pasenau: I just wondered what would come out of it. I was very curious and I also wondered how much I would change in a year, and it was also the year where I had a big exhibition and a lot of things happening.

Isabella Burley: I think it’s capturing that very fleeting moment in your early twenties where you have that freedom to experiment with clothing as [a means of] self-expression; there’s so much freedom to it. Later on – not necessarily as you get older – but if you’re then making work, you just want to be in practical functional clothing.

MP: I have destroyed so much clothing in my studio – glued and stained, and my boyfriend gets mad like ‘you need working clothes!’ You have to have time to do it too.

BH: How much time did you put into each photograph – or are they very much snapshots?

MP: They’re snapshots. In some of them, if I’m naked that’s because it’s at the end of the day. The series is very framed, from the beginning – it’s more science-y, like a social project or an experiment. It’s also not about me, it’s about time.

IB: It’s patterns and things in our behaviour that you’re being confronted with which I think is such an interesting thing. Your emotional state varies, if you just had a fight with your boyfriend and you had puffy eyes, or if you’re happy or if you’re like ‘fuck you’ or whatever, it’s nice to see all of that.

BH: How long have you known each other?

IB: It was actually October 11, 2018 that we met, the day you started the project. Our mutual friend Elise By Olsen had a dinner in London, and Antonia [Marsh] was there too. Maria had copies of Whit Kind Regrets, her first book and it was this insane hardback 30-page thing that she’d self-published – it was all done through crowdfunding. And to have the balls to do such an insanely big monograph I thought was incredible.

MP: Yeah it had just come out. I raised around £10,000 because I had already started the printing process – I was like what the fuck am I doing! It went well though.

IB: So Antonia and I got copies of the book that night. I’ve only just realised that the first night we all met was the first day that the project started, which is really nice. Antonia mentioned the project to me, and we thought we’d do something later this year but a space opened up so we literally put the show together within three weeks.

BH: And is this your first time curating?

IB: Yeah. It’s nice because I’ve known Antonia for so many years and I’m a big fan of the Soft Opening space in Piccadilly, I walk past it every day. Obviously I’m such a big fan of Maria’s work too and what was exciting about this is that it is so specific, an entire year of work. How do you deal with an entire year of work in such a small space that is also such a public setting? Over one million people must walk past the space every single month and I’m so curious about how people interact with it. With the screen, the works appear chronologically from day one through to day 365 and then go backwards. The works aren’t dated, so a viewer can walk past and they have no idea what the context of it is. The sculpture came about from a Skype that we all did together. Clothing is such a big part of this series and I think to have something physically represented is important.

MP: Yeah it fitted very nicely. Also if the screen dies or something, if the electricity goes off, then we have the sculpture there!

BH: When you started it, did you have any idea of wanting to present it this way?

MP: No, I wanted it to be a book. It would be nice to show all of the pictures at once on walls, but that’s very expensive so I’ll do that when I get older. I also really want to make another year when I’m older so I’ll have this year and another year.

IB: I love the idea of revisiting this series again when you’re 50 and seeing and comparing, that would be really cool.

MP: For me, it’s a lot about being able to see what was happening when I did it. It’s not about each and every picture being perfect.

BH: It’s so much like a diary – having something like this for a such specific chunk of time is amazing. Have you ever kept a kind of diary in a similar precise, regimented way?

MP: Not like that but I’ve always liked taking pictures every day, my first book was about that. But now I actually take less and less pictures. I work with different [media] and I still like to take pictures, but I don’t want to get bored of photography. If I do other stuff too I think it’s better for me. Also it’s very difficult to get a great picture.

IB: We live in such an oversaturated image culture. This is one of the things that I remember talking to you about when we first met, how you don’t put your work on social media. So many people who are in the bracket of a ‘young artist’ or a ‘young photographer’ get overexposed in such a toxic way that is not sustainable, and I think you’ve always been very conscious to remove yourself from that in some way that is very clever.

MP: I don’t want to be on Instagram and I’m not posting anymore. There’s so much tension and I don’t want to have that in my life. Everything is so fast and I want to start working in the dark room again, I want things to be slower and slower. My Instagram is my Instagram, it’s not my art. It’s so strange just because you’re an artist people think that Instagram is your portfolio. But I couldn’t get the money for the first book without Instagram so...

IB: It’s a weird one. We’re only sending 12 images from the 365 to press, so the only way someone can experience this body of work is by physically going to the space. But then because the images are changing every two seconds, there’s no full way for someone to see the entire project without standing and watching it for 20 minutes.

MP: And even then you don’t see the nudes – it’s censored.

IB: We had to omit four of the images. I love the idea that for someone to fully see the scope of that project, they can’t. They can see 95 per cent of it by coming to Piccadilly but then they haven’t seen the nudes. Like you say, you might print everything and you’ll be able to show the nudes because you’re not showing in a public space, inside one of the biggest stations in London. I remember when I was speaking to you about the works you were saying making this series has been more intimate than some of your earlier nude stuff.

MP: Yeah, when I was sitting and scanning it, you can really analyse how my year has been. I think it’s more personal than even taking a close up of my pussy because that’s just one thing but when it’s your whole life, it’s very intimate.

IB: We all have patterns in our behaviour or things that we do, we’re all quite predictable to some degree. It’s so immensely personal to you but something that is so relatable – that also plays with the public-private thing, that dialogue is happening because of the space.

BH: I think it’s definitely relatable. I bet so many people would love to do something like this.

IB: But we’re in such an image culture of documenting that we do take pictures every day, but not to view that as a whole body of work or to see the patterns of behaviour or your changing emotion or remember what happened on those days.

MP: Actually back in Norway I met an old guy on the bus and we talked about the photos because he was very interested in photography, and he was like ‘Yeah, I’ve done that too! I’ve taken pictures every day from my window’ and I was just like, that’s so nice. He wasn’t going to show it or anything, he was just doing it for himself. I love that.

BH: Do you have a favourite from the series?

MP: I was really excited about the one with just the Buffalo shoes.

IB: Yeah like fully nude. I think that’s my favourite. Also, that was quite near the end of the project so I think you can sense... You know when you’re forced to do something but you’re also the person who decided to force yourself to do it, so by the end you’re just like, fuck this.

MP: I think it’s nice that it’s on the film because I didn’t have the full control of how it was going to be. There’s a series of pictures where one image fades out, it gets abstracted and that’s because I opened the camera when I was drunk.

IB: So there are seven or eight images where it’s completely abstract, like washed out in a really psychedelic way.

MP: And then the last picture is me very drunk downstairs looking like a guilty person. First I was mad at that but then I was like that’s the magic of the film, that’s why I took it. I think that’s so interesting.

365 Days of Pasenau is at Soft Opening, Piccadilly Circus, from January 31 – March 29, 2020.