As the Barbican’s blockbuster exhibition Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography opens, a look at how some of the female image-makers in the show approach the multifaceted male experience in their work

In a series of rooms set over two floors in the Barbican Centre, new exhibition Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography showcases the work of nearly 60 image-makers who address the complexities and contradictions of what it means to be masculine. The mammoth show features work dating back to the 1960s until the present day – totalling almost 300 pieces – by photographers who eschew or subvert traditional notions of masculinity. At a time when the actions of men are scrutinised and we are well-versed in what might constitute hegemonic, toxic, or fragile masculinity, Liberation Through Photography explores the varied nuances of the male experience, beyond stereotypes, and how they have played out in artistic imagery over the decades.

Among the many historical and contemporary male image-makers who tackle masculinity in their work – from Robert Mapplethorpe, Hal Fischer and Peter Hujar to Sam Contis, Jeremy Deller and Sunil Gupta, to name a few – there are a number of female photographers featured in the exhibition. These women address, interpret and subvert codes of masculinity, and the gender stereotypes that it often invokes, in myriad ways.

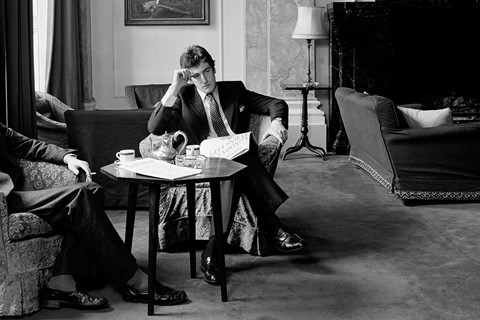

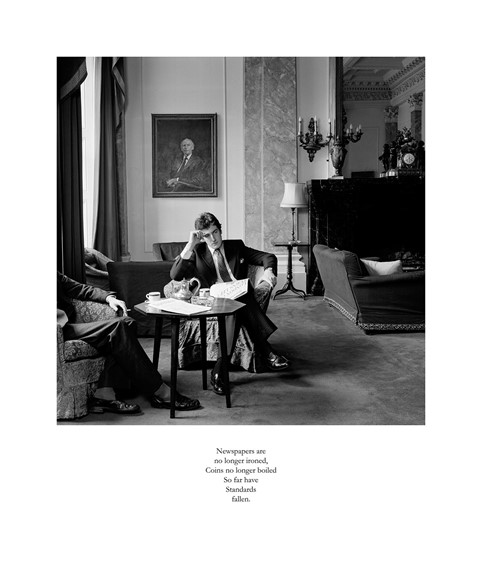

Artist Karen Knorr’s series Gentlemen documents the men of the patriarchy in 1980s London. The series comprises portraits and interiors taken inside men-only private clubs throughout the city, captioned with text formed from speeches and news bulletins – “Men are interested in power. Women are more interested in service”, reads one. Exposing how hegemonic masculinity is closely tied to whiteness, wealth and privilege, Knorr satirises this powerful niche of British society. A sculpture by Clare Strand is on show in the same section of the exhibition as Gentlemen, a towering stack of 68 copies of Men Only magazine; both women’s work confronts the viewer with an exclusive, yet universally accepted, form of masculinity. The equally revered ‘macho’ man is explored by Aneta Bartos, who appears – somewhat unsettlingly – alongside her bodybuilder father in the series Family Portrait.

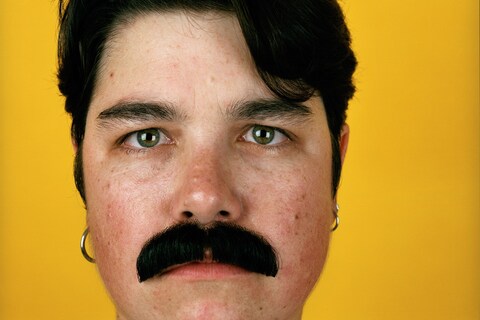

The 1970s-coined term ‘male gaze’ describes the depiction of women in the arts from a male point of view. A number of artists in Masculinities work to subvert the male gaze, by directly addressing how women are objectified, in turn objectifying men, or questioning gender stereotypes. Feminist artists like Ana Mendieta – whose series of photographs depicting the artist as she glues facial hair from a man’s beard to her own face covers a wall of the exhibition – incorporated the body into physical, performance-like work in order to question what makes something masculine.

In turn, Laurie Anderson’s arresting 1973 series Fully Automated Nikon (Object/Objection/Objectivity) was a response to being on the receiving end of mundane male behaviours and micro-aggressions. Anderson photographed men who cat-called her, and annotated the images with both what they said to her and how they responded to being objectified themselves (mostly, and unsurprisingly, not well). Annette Messager and Tracey Moffatt also take the power of objectification into their own hands: in Moffatt’s film Heaven (1997) she documents surfers as they return from the beach and change clothes by their cars; Messager’s singular form of street photography zooms in on the crotches of men who pass by her camera.

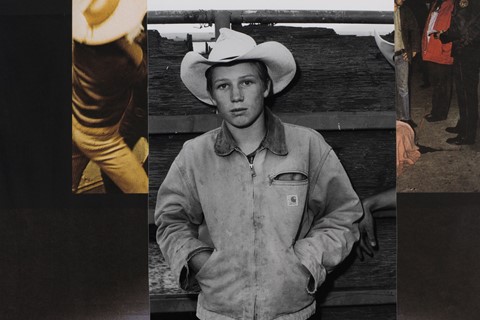

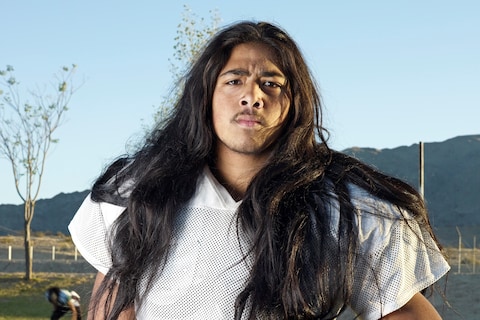

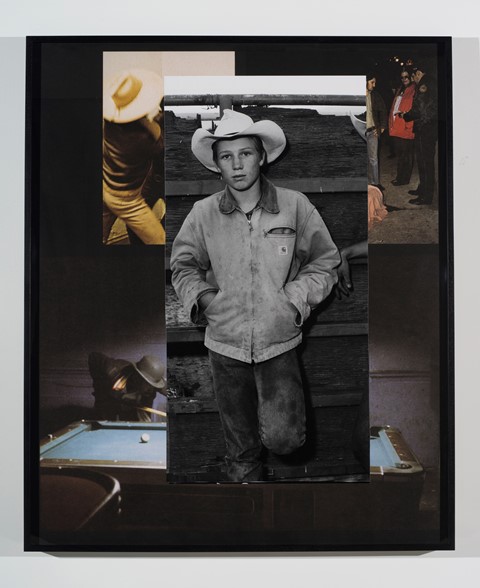

For a selection of the female artists whose work features in Masculinities, their photographic output does not interrogate masculinity from an explicitly female perspective, but rather reinterprets established male codes by honing in on typically male groups, relationships and subcultures, or elevating aspects of masculinity that are not always mainstream. A section of the exhibition dedicated to the black male experience showcases striking portraits by Deana Lawson and Liz Johnson Artur. It’s here, and in the photography of Collier Schorr and Catherine Opie – in Schorr’s series Americans, scenes of violence or pictures of African Americans are overlaid with portraits of adolescent cowboys – that the gender of the image-maker does not feel as pertinent as, for example, their perspective as queer or a person of colour. “I’ve never had ‘permission’ or been associated with a collective or a movement,” Schorr said in an interview in Aperture magazine in 2017. “The politics of the work left people uncertain of my identity. Was I a gay male? If I had been a gay male, I think there would have been more support for the work, because there is a tradition of gay men making work about male beauty.”

The strength of Masculinities is in how extensively it explores the multifaceted and ever-evolving male experience, from rigid and traditional gender views to freewheeling celebrations of alternative masculinity. Seeing masculinity from the perspective of women – whether as a timely criticism or an astute observation – forms a small but mighty part of the unmissable exhibition.

Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography is at the Barbican, London, from February 20 – May 17, 2020.