The seminal artist Louise Bourgeois would turn to drawing as a means of therapy – in times like these, perhaps her complex and colourful works can offer us some relief too

Living through a pandemic, and all the unfamiliar changes and challenges it incurs, makes for anxious times. When the late artist Louise Bourgeois felt a wave of worry, she would draw. “I know that when I finish a drawing, my anxiety level decreases,” she once said. “When I draw it means that something bothers me, but I don’t know what it is. So it is the treatment of anxiety.” In these uncertain times, art institutions the world over have had to close in order to slow the spread of coronavirus, and therefore find alternative ways of presenting art in a suddenly much more virtual reality. For its inaugural online exhibition, international gallery Hauser & Wirth presents Louise Bourgeois: Drawings 1947 – 2007 – which feels a pertinent choice, given the relief the artist herself sought out in creating the works.

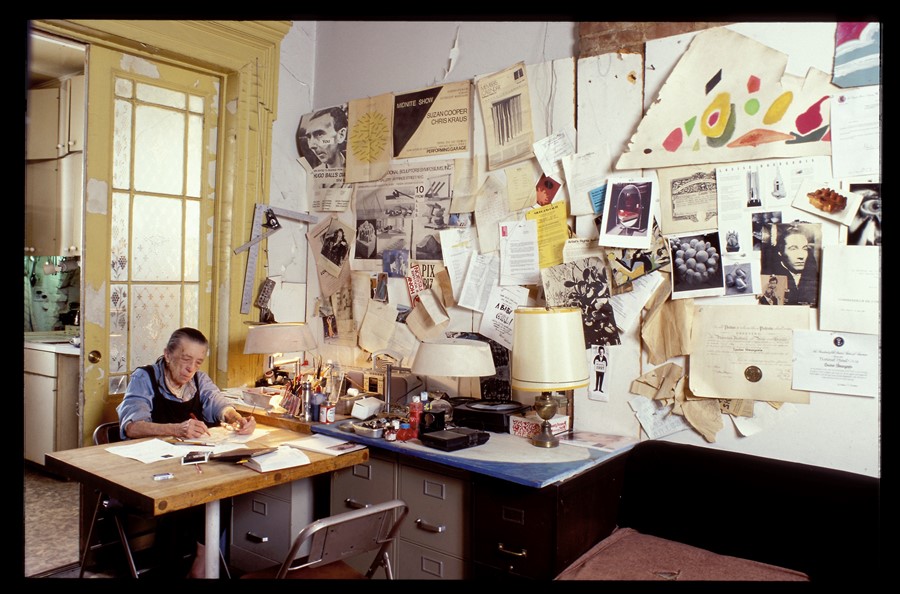

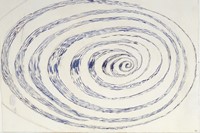

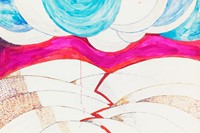

Famed for her spidery sculptures, fabric prints and etchings, Bourgeois began drawing at a young age by helping her parents in their tapestry restoration studio outside of Paris. Spiders and spirals recur throughout Bourgeois’ drawings – she likened her beloved mother, who died when the artist was in her early twenties, to a spider – and her pieces move from abstract to realistic, rendered in ink, watercolour and pencil. Bourgeois herself said of these variations: “The realistic drawings are a way of pinning down an idea. I don’t want to lose it. With the abstract drawings, when I’m feeling loose, I can slip into the unconscious.”

The drawings in the Hauser & Wirth exhibition span decades, and were chosen by Jerry Gorovoy, a former studio assistant and friend of Bourgeois’ who is now president of the Easton Foundation, set up in the late artist’s name. Over the course of her life, Bourgeois consistently turned to art as a means of therapy; she would use her creativity to work through intense emotions – both positive and negative. “Like a sufferer of Tourette’s syndrome, she always felt that she had to confess everything, which could be uncomfortable for others, and once called herself the woman without secrets,” Gorovoy wrote following her death in 2010. “In her art she was utterly fearless and in real life she said she was the mouse behind the radiator.” Bourgeois described art as “a guarantee of sanity”.

The therapeutic nature of Bourgeois’ art is also somehow universal, extending beyond her own relationship with the work and resonating with viewers in a unique way. “The first time I saw her work it felt so personal,” the designer Simone Rocha told AnOther last year; Rocha’s Autumn/Winter 2019 collection was inspired by Bourgeois, and featured spiderweb prints and embroideries. “I just felt like my feelings were down on a page ... It was like my teenage diaries, but in a more beautiful form, obviously.” The drawings were diaristic for Bourgeois, too; a place for her to temper anxieties, work through childhood memories, and express emotions. “I have kept a diary as long as I can remember, and drawings are really another kind of diary,” she said.

Bourgeois’ complex and colourful drawings – a constant throughout her life, though not as widely seen as famed series like Cells or her gargantuan Maman sculpture – were a significant part of her artistic practice, but also served a purpose. She created art relentlessly until her death at the age of 98, seemingly as a way to stay sane. In times like these, a pause to look at Bourgeois’ compelling drawings might help us to do the same.

The online exhibition Louise Bourgeois: Drawings 1947 – 2007 runs from March 25, 2020.