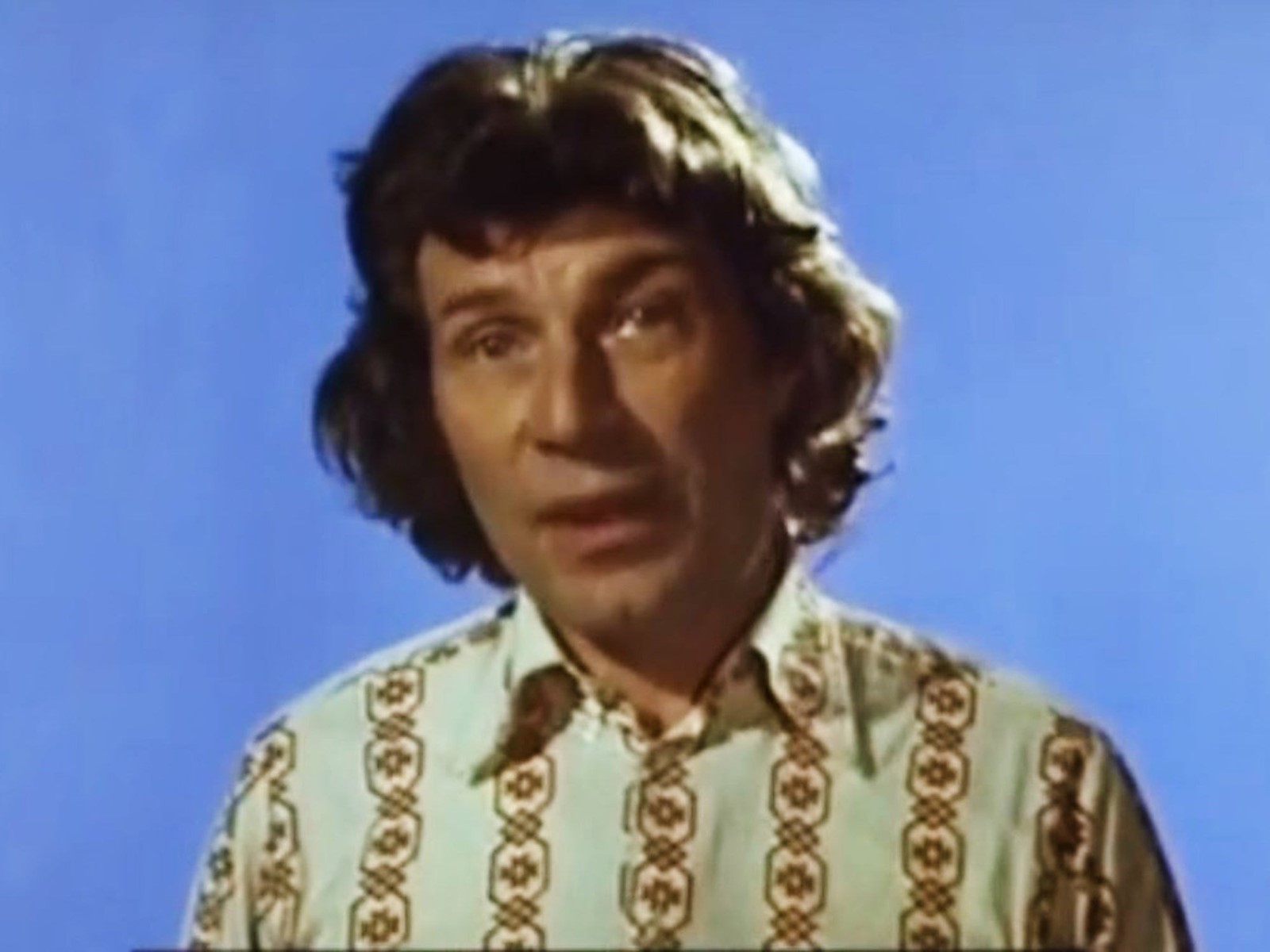

John Berger and I share a birthday. He is the person with whom I am most guilty about being a slack correspondent. His insistence on pen and paper and resistance to e-ways lands us slap back in the land of my hieroglyphically illegible handwriting and slows up dialogue into heel dragging gaps of months at a time ... I met John first in 1988 when we made a film – Play Me Something – together in the Hebrides. He is one of the straight up straight down wisest men I know and I love him through and through. His contribution to our understanding of the spiritual and political significance of artists and artists’ work cannot be overstated: he is a storyteller, a humanist and a revolutionary to his toes – Tilda Swinton

It began like this. About ten years ago, Nella was in Moscow, staying with some old Russian friends. One day she passed a junk shop. Maybe it considered itself an antique shop. People at that time in Moscow were selling whatever they could find in their cupboards because wages and pensions had collapsed. One could buy family silver on street corners. For Nella, secondhand shops in any city in the world are as irresistible as dictionaries. She goes in to turn the pages. Often she finds a new word. This time she found a painting. Oil on canvas. A small still life of some red chrysanthemums.

She bought it. Signed and dated: Kleber, 1922. It cost less than a song. Far less. Back in Paris she didn’t know where to hang it. It looked right nowhere. Here and there little flakes of paint – the size of salt grains – had fallen off, and you could see the white of the canvas. When in doubt Nella waits for the doubt to disappear. It usually does.

She put the canvas in a black plastic sack in the garage alongside other packages of clothes, books and nondescript objects forgotten by those passing through. Before hiding it away she showed it to me, and I thought: flowers in a nineteenth century interior, a hundred-year-old dream of a new future, almost the same as the past, could only be Russian. The chrysanthemums were lying on a narrow ledge. Behind them stood an empty glazed vase. Were they about to be arranged in this pot? Or had they been taken out, a little too early, to be thrown out? Either way, better to leave it in the garage.

Time passed. One year the garage got flooded. Nella took the painting out of its sack and propped it up in various corners of the lived-in rooms. More paint had flaked off, leaving more spots of white canvas. The damage was by now far more arresting than the image.

“I can’t bring myself to throw it away,” Nella said last week. I found myself replying: “I’ll try to repair it. It can’t be restored properly, it’s too far gone and I don’t have the skill. I can just colour the white spots.”

So I started. Mixing the colours on a white saucer. For many years I hadn’t used oil paint. When drawing I use inks or acrylic. No other colours mix like oil colours. You search touch by touch for a timbre on the saucer and then you discover whether or not, when applied to the canvas, the colour matches the “voice” you were searching for.

There were hundreds of white flaked-off spots to cover. Blackish crimsons for the flowers in shadow. Guitar browns for the wood of the drawer under the ledge. Shellfish greys for the walls in the corner where the ledge was. An indescribable magenta pink for the petals in the light. Everything suggested the room was small, with probably, in 1922, many people living in it.

I lost count of time as I covered white spot after white spot. With this loss of a sense of time, my sense of identity slackened. Touch by touch, tone by tone, I was approaching a systematic vision which belonged to a pair of eyes which until then were not mine. These eyes were in another place.

I was observing flowers thrown on a ledge in the corner of a small room in the afternoon light of a late September day in the year 1922. The Civil War was over. It was nevertheless a year of widespread famine. Nearly all the white spots are covered.

I went to look at the painting several times during the night. Or rather to look at the corner in the small room. I couldn’t leave them like that. Neither the flowers on the ledge nor the painting. You could still see where the white spots had been. Pockmarked. I had to return them in better condition to that late September afternoon, before the dreaded cold of winter arrived – when there would be little to burn for keeping warm.

I needed to paint more freely. Yet I could not treat the painting as mine; it was Kleber’s. More thoroughly his than I could have previously imagined. If I wasn’t free, the light wouldn’t come back.

The next day early in the morning I continued. Sitting with the canvas on my knees and the saucer on the table beside me. There are some lines in a poem by Akhmatova on the theme of mourning, which refer to a chrysanthemum crushed by a boot on a sidewalk. These lines were written twenty years later. The crimson chrysanthemums in this still life are still innocent.

Now I paint freely, inspired by the longing of what is there on the canvas. I discover how, in the corner of a small room, the light – falling on two peeling walls and half a dozen thrown-down flowers – is a kind of promise from a distant unimaginable future.

The job is done. I feel elated. There it is, a painting by Kleber, 1922. A moment has, for a moment, been saved. This moment occurred before I was born. Where is it now? Is it possible to send promises backwards?

This story originally featured in the Autumn/Winter 2004 issue of AnOther Magazine.