Originally taken 20 years ago, Justine Kurland’s captivating series Girl Pictures is now published by Aperture. Here, as part of our #CultureIsNotCancelled campaign, she explains the series in her own words

This article is published as part of our #CultureIsNotCancelled campaign:

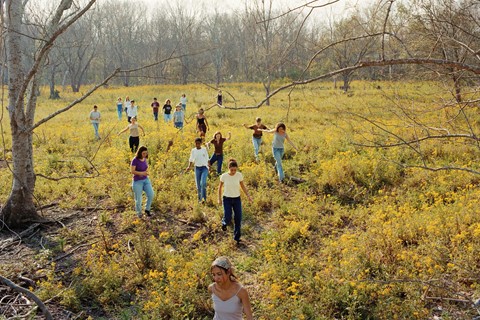

Justine Kurland admits to having “terrible timing” when it comes to publishing photography books. “The first book I made with Aperture, Highway Kind, was released the day Trump was elected, and now Girl Pictures comes out in the middle of Covid-19,” she writes to AnOther over email as her latest book is published. The photographs in Girl Pictures were taken 20 years ago, and depict unruly teenagers in the equally wild landscapes of America. Kurland staged her “standing army” of teenage runaways as independent, unapologetic and fearless. “My runaways built forts in idyllic forests and lived communally in a perpetual state of youthful bliss,” the New York-based photographer writes in Girl Pictures, this new Aperture edition of which includes previously unpublished images from the series. “I wanted to make the communion between girls visible, foregrounding their experiences as primary and irrefutable.” A short story by Rebecca Bengal entitled The Jeremys is published in Girl Pictures, and encapsulates this longing for rebellion.

The magnetic anarchy of girl bands like The Runaways inspired Kurland and her defiant teenagers. “The music gave voice to rage, but maybe it was their haircuts and clothing, and their badass rebellion – I wanted to be them more than I wanted to listen to them,” she says. The extensive travelling that Kurland undertook for Girl Pictures preempted a long-held interest in being on the road; her 2016 book Highway Kind was her own take on the storied and much mythologised road trip in photography, looking at “the cracked, oiled, and stained underbelly of cars, and considering them as a fact in the landscape as well as the support of my trips”. For over ten years, Kurland lived and travelled the USA in a van with her son, embarking on road trip adventures and taking photographs along the way.

The freedom depicted in Girl Pictures – both of the girls and of Kurland, driving across the country behind the scenes – easily invites feelings of nostalgia, especially during times of stay at home orders and lockdowns. “And yet,” Kurland says, “it might be more important to think about these pictures now than ever, as a bright spot in a lot of dread and unknowing. Maybe these pictures can suggest new possibilities for the future. Maybe when we pick up the pieces we can form a community built on harmonious ways of living with each other and in nature.” Here, she shares the story behind Girl Pictures, and what it’s like to revisit the series two decades on.

“Being a teenager means you haven’t yet fully signed on, politically, culturally or economically. If you simply refuse to grow up and toe the line – why would you want to, anyway? – you can create a world for yourself, one that’s bearable to live in. I built on and corrected some of the tropes surrounding the representation of teenagers; these pictures were not solicitous renditions of hypersexualised children. Instead I drew from artists such as Mary Ellen Mark’s pictures of Tiny, Jim Goldberg’s Raised by Wolves, and Susan Meisalas’ Prince Street Girls and films such as Agnes Varda’s Vagabond and Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock. But really the girls were surrogates for myself. Behind the camera, I was also somehow in front of it – a girl among other girls. The photographs testified to my relationship to them and their relationships to each other. I wanted to build lines of communication through which the girls could support each other.

“I intentionally used cars, highways, and truck stops in my photographs. In Making Happy and Ship Wrecked, a broken-down car serves as an alternate home for the girls; in Hitchhikers and Truck Stop, the girls might be looking for rides; in Pink Tree, a girl hovers between two modes of travel, the river and the highway. At a certain point I began taking extended road trips so that my process of making the photographs corresponded to the same adventure I asked the girls to enact. This began a two-decade-long commitment to road trip photography.

“It’s wild because many of the girls are mothers now – I’m still in touch with several of them. At first I only photographed girls I knew, but once I began taking longer trips, I had no choice but to cruise through towns trolling for girls. Looking back it seems very creepy and predatory. Many girls said no, but the ones who agreed were the ones who shared my vision of a girl utopia. They would introduce me to their friends, show me places in the woods where they hung out, and collaborate in the narratives we staged.

“There were two girls in Texas who told me they were going to ‘get up out of there’ as soon as they could. I remember they carried a sickly kitten around all day. I picked Alicia up on a street in New York City and she introduced me to her friend Rebecca, who had an OCD tick of walking so her knees kicked up, like a show pony. I met Gaea when she was 13 at a commune in Virginia; she crossed the river in front of her house on a rope, Tarzan style, wearing a feather boa and chunky high-heeled boots. Now she’s about to have her first baby. But I think about Lily the most; she died ten years after I met her and, when I see her in my pictures, my heart skips a beat.

“Revisiting the Girl Pictures now – in terms of our current political situation, with a President that brags about grabbing women by the pussy and the rollback of human rights and environmental protection – it seems especially important and relevant to think about alternative societal models. I pictured the girls as a standing army united in solidarity, outside the margins of home or institution, working together to build a community that foregrounded their experience as primary and irrefutable. These photographs were a call to action, then as now.”

Girl Pictures by Justine Kurland is available for pre-order now, published by Aperture.