lt’s a tradition stretching back more than 3,000 years, a secret passed from master to disciple across the ages. Now Chinese acrobatics is battling for attention against an emerging global entertainment culture. On the west side of Shanghai, 89 students and a visionary Leader are keeping the faith.

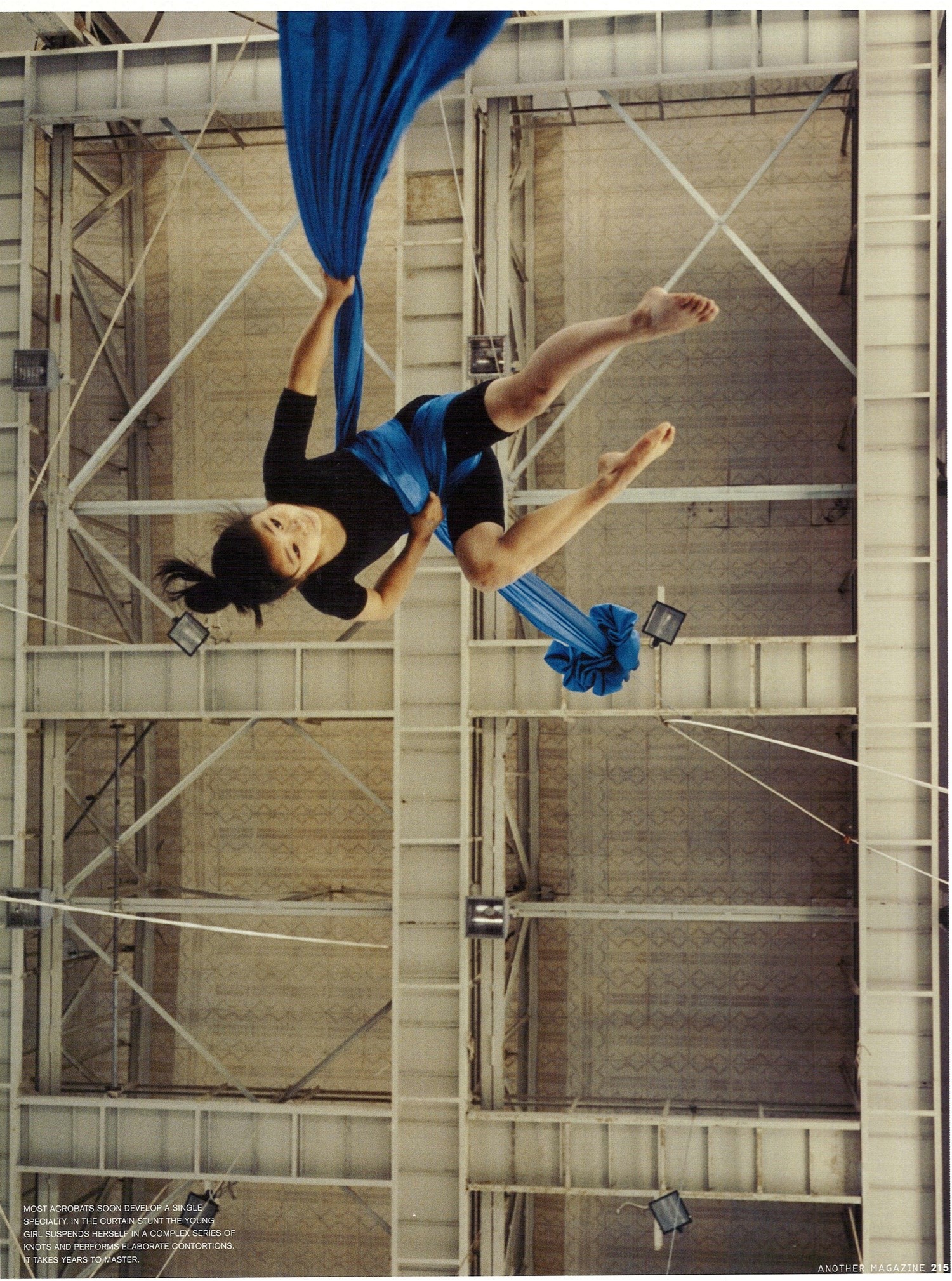

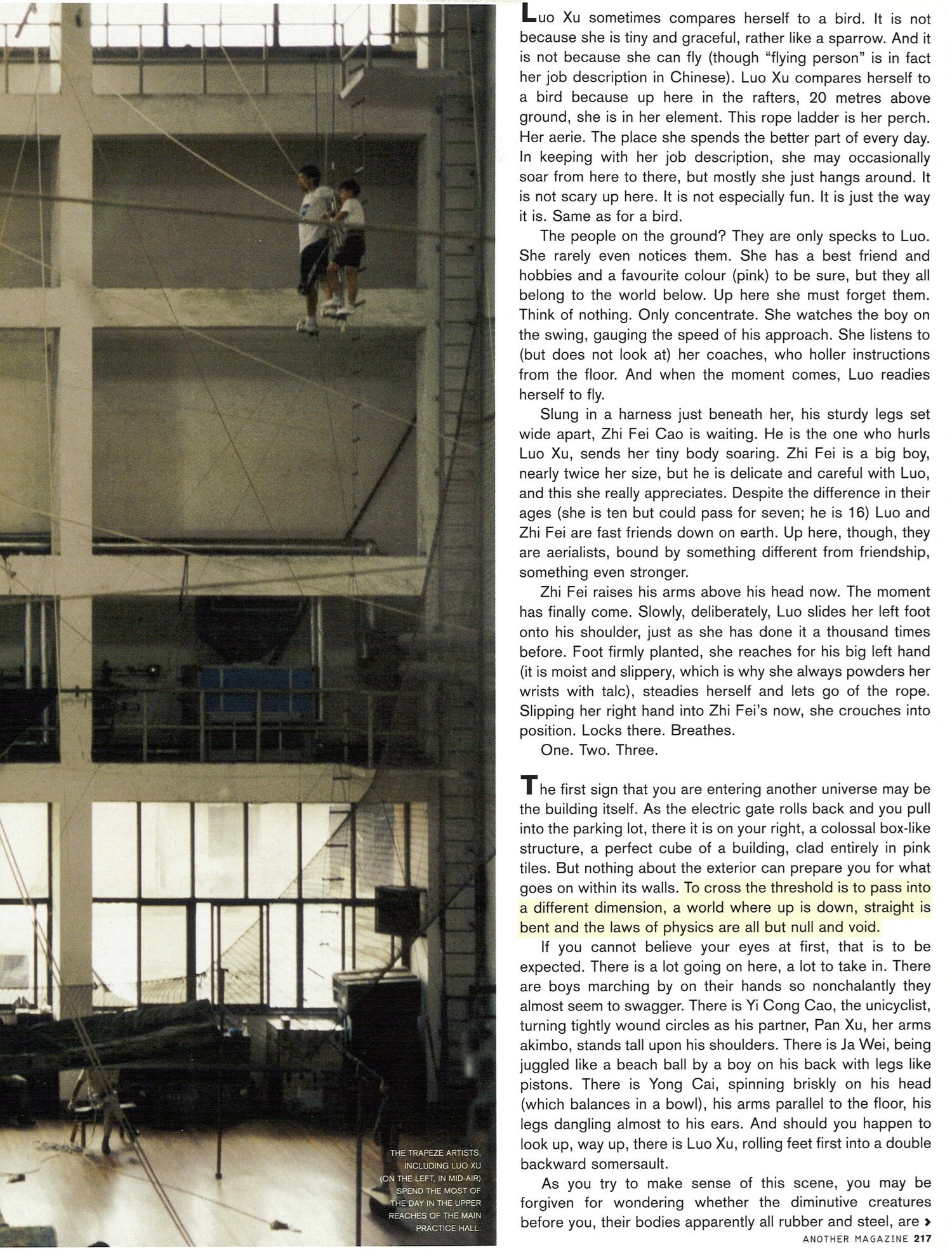

Luo Xu sometimes compares herself to a bird. lt is not because she is tiny and graceful, rather like a sparrow. And it is not because she can fly (though “flying person” is in fact her job description in Chinese). Luo Xu compares herself to a bird because up here in the rafters, 20 metres above ground, she is in her element. This rope ladder is her perch. Her aerie. The place she spends the better part of every day. In keeping with her job description, she may occasionally soar from here to there, but mostly she just hangs around. lt is not scary up here. lt is not especially fun. lt is just the way it is. Same as for a bird.

The people on the ground? They are only specks to Luo. She rarely even notices them. She has a best friend and hobbies and a favourite colour (pink) to be sure, but they all belong to the world below. Up here she must forget them. Think of nothing. Only concentrate. She watches the boy on the swing, gauging the speed of his approach. She listens to (but does not look at) her coaches, who holler instructions from the floor. And when the moment comes, Luo readies herself to fly.

Slung in a harness just beneath her, his sturdy legs set wide apart, Zhi Fei Cao is waiting. He is the one who hurls Luo Xu, sends her tiny body soaring. Zhi Fei is a big boy, nearly twice her size, but he is delicate and careful with Luo, and this she really appreciates. Despite the difference in their ages (she is ten but could pass for seven; he is 16) Luo and Zhi Fei are fast friends down on earth. Up here, though, they are aerialists, bound by something different from friendship, something even stronger.

Zhi Fei raises his arms above his head now. The moment has finally come. Slowly, deliberately, Luo slides her left foot onto his shoulder, just as she has done it a thousand times before. Foot firmly planted, she reaches for his big left hand (it is moist and slippery, which is why she always powders her wrists with talc), steadies herself and lets go of the rope. Slipping her right hand into Zhi Fei’s now, she crouches into position. Locks there. Breathes.

One. Two. Three.

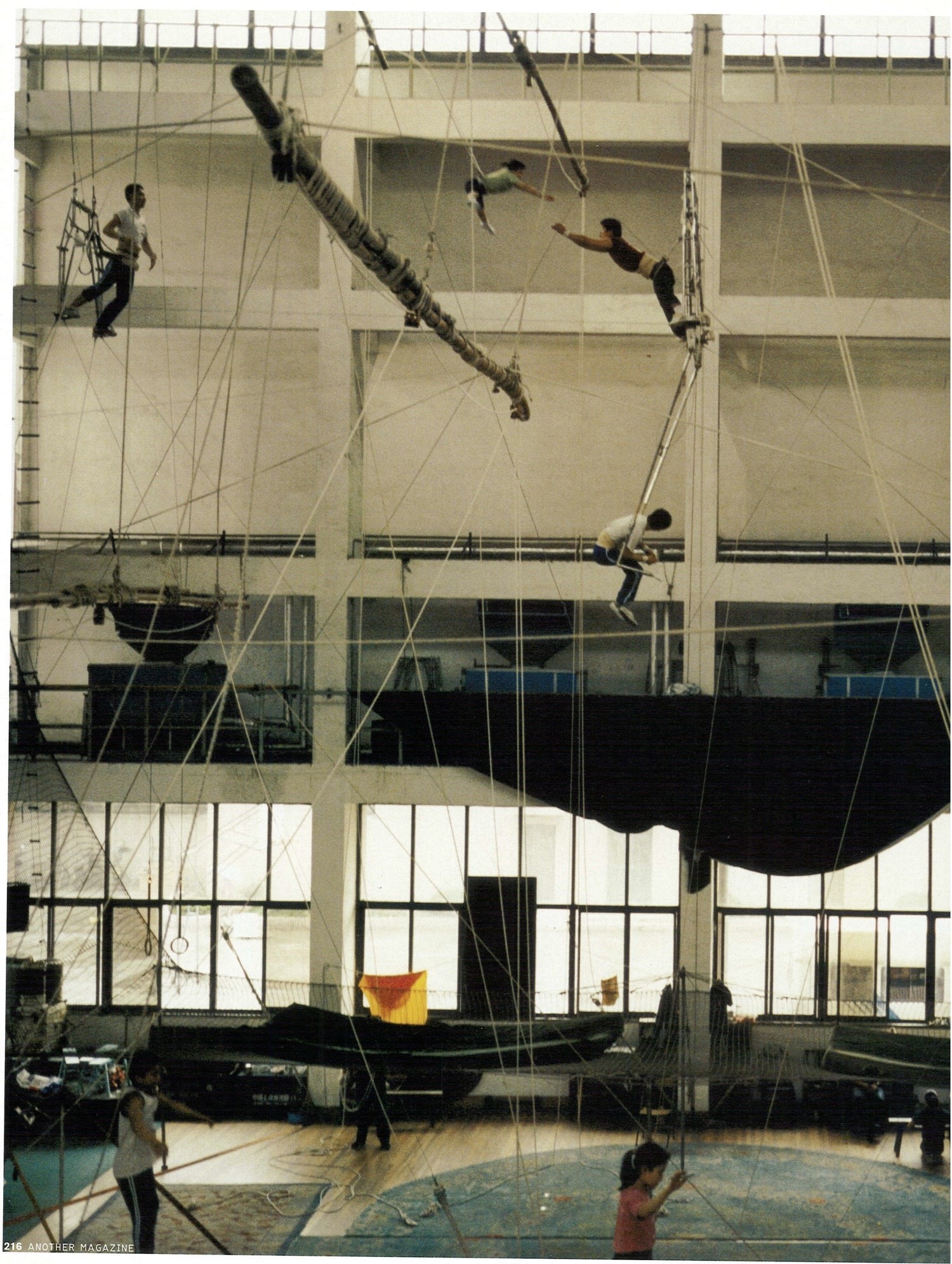

The first sign that you are entering another universe may be the building itself. As the electric gate rolls back and you pull into the parking lot, there it is on your right, a colossal box-like structure, a perfect cube of a building, clad entirely in pink tiles. But nothing about the exterior can prepare you for what goes on within its walls. To cross the threshold is to pass into a different dimension, a world where up is down, straight is bent and the laws of physics are all but null and void.

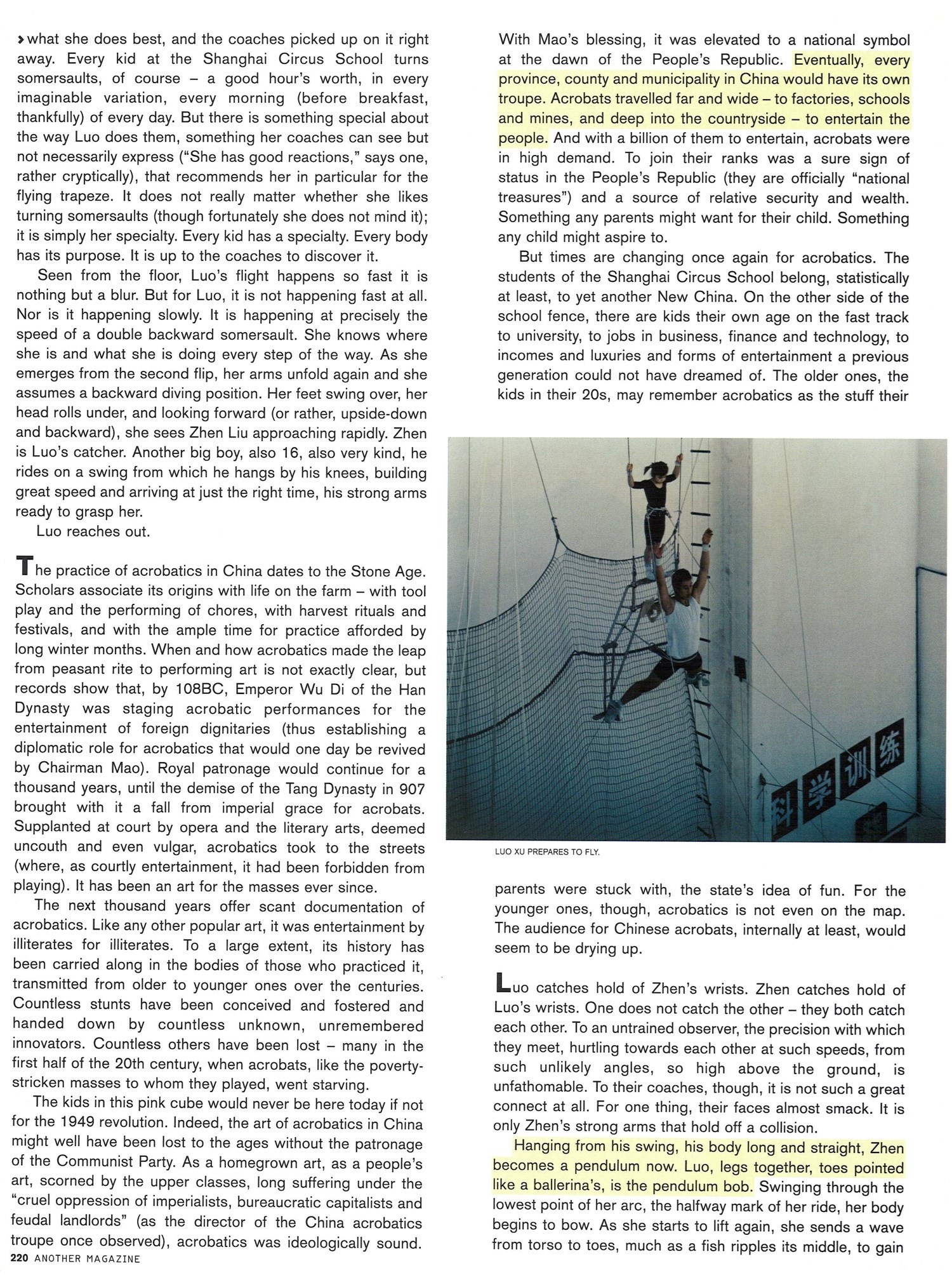

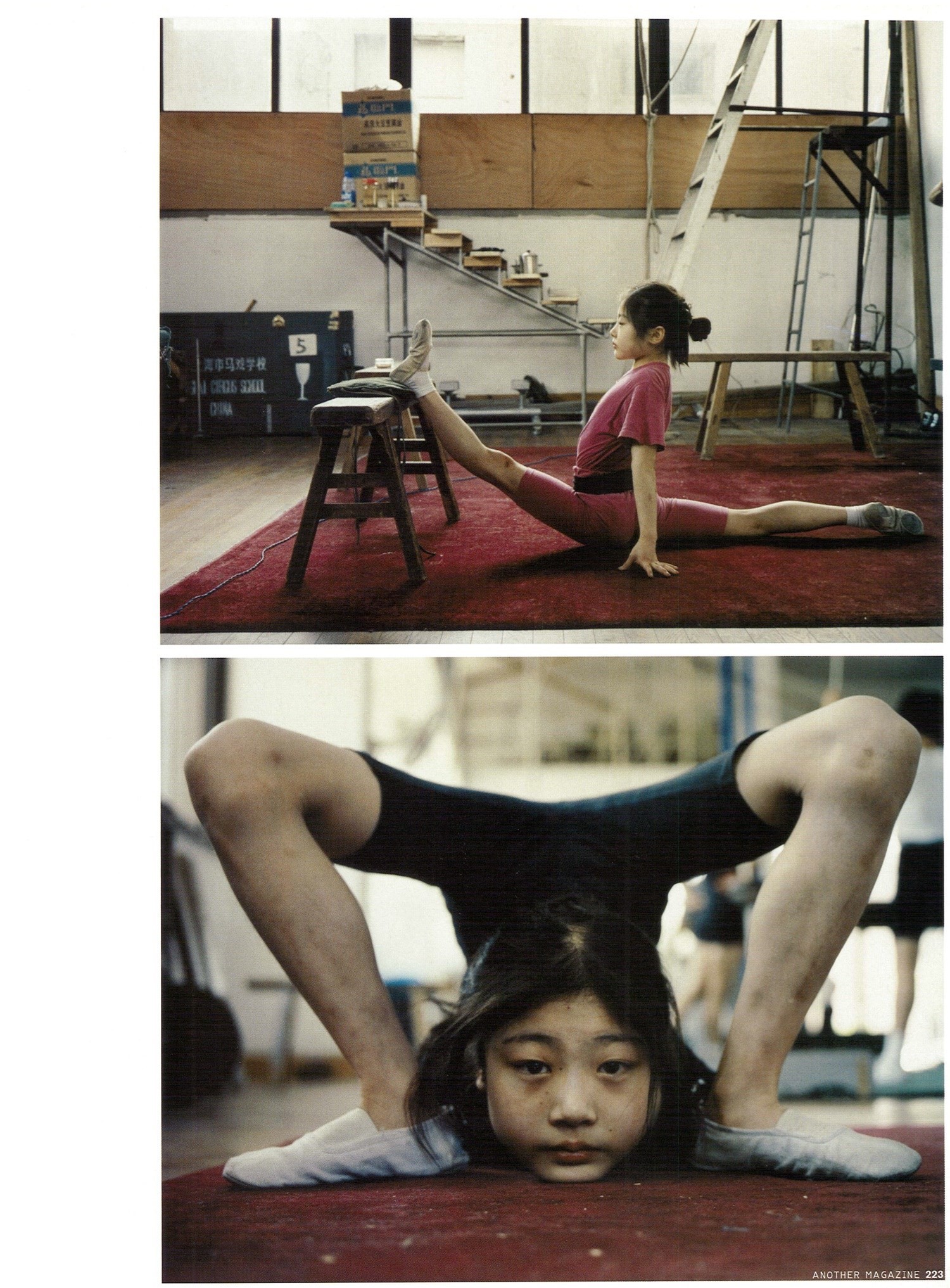

If you cannot believe your eyes at first, that is to be expected. There is a lot going on here, a lot to take in. There are boys marching by on their hands so nonchalantly they almost seem to swagger. There is Yi Cong Cao, the unicyclist, turning tightly wound circles as his partner, Pan Xu, her arms akimbo, stands tall upon his shoulders. There is Ja Wei, being juggled like a beach ball by a boy on his back with legs like pistons. There is Yong Cai, spinning briskly on his head (which balances in a bowl), his arms parallel to the floor, his legs dangling almost to his ears. And should you happen to look up, way up, there is Luo Xu, rolling feet first into a double backward somersault.

As you try to make sense of this scene, you may be forgiven for wondering whether the diminutive creatures before you, their bodies apparently all rubber and steel, are human beings at all. In their strength and daring, they seem almost superhuman; in their serene refusal of pain, almost automatons. But rest assured, though you may have to spend some time with them to see it for yourself, these are very real people indeed. If they happen to make the seemingly impossible seem easy, it is not magic, it is their art.

For these are the students of the Shanghai Circus School, 89 of them in all. They are the recipients of a tradition that stretches back, unbroken, more than three millennia. The skills they are gradually acquiring, and the methods by which these are imparted, belong to the secret code of Chinese acrobatics, never written down, carefully guarded through the ages and passed along from masters to chosen apprentices all the way down to this very day, to this very pink building on the west side of Shanghai.

Founded in 1989, the Shanghai Circus School was the first, and is far and away the greatest acrobatics school in China. They may be only human, their small bodies subject to the same laws of gravity as yours and mine, but the kids in this building are the rarest of physical specimens. Their coaches have crisscrossed China to find them, stopping in at dance and gymnastics schools and physical education programs in most provinces of the land. Each one has been painstakingly selected from thousands of hopefuls. Each one has been measured, examined, observed and put through his or her paces many times.

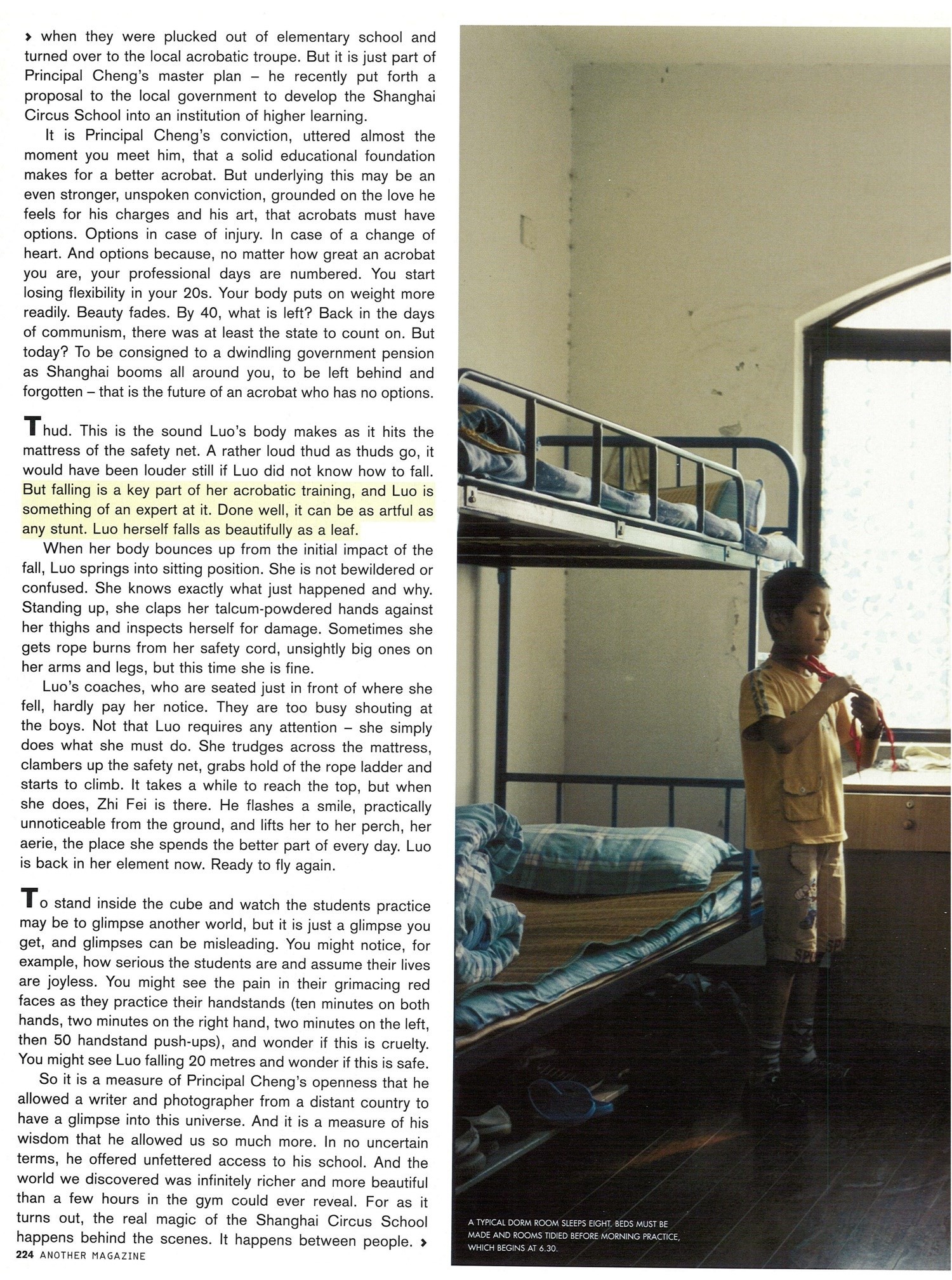

As with all child prodigies, the kids in this pink cube have made gigantic sacrifices for their art. Many of them are still too young to understand what they are giving up, and what they may expect in return. For seven full years of their young lives (assuming they are not weeded out before), starting as early as six, the students of the Shanghai Circus School will spend their days almost totally confined to their urban campus – a small plot of land, much of it asphalt, with a patch of grass and three pink-tiled buildings. They will seldom see their families. They will lose touch with friends and the whole wide world outside. They will do it for their art.

Before you start feeling sorry for them, though, it might help to see things from their point of view. Wen Juan Dai, 18, first started dreaming of being an acrobat when she saw it on TV. She was overcome, she says, by its beauty. When the coaches came recruiting at her school in Anhui Province, she could hardly believe her luck. Ya Min Hu, 16, who is from the Shanghai area, pushed and pushed his parents to bring him here, so he could have a try out ; today he is turning quadruple forward somersaults in mid-air. And then there are the new recruits: Chi Ling Wei, 15, and her twin sister Chi Miao came all the way from distant Guang-Xi to join the school. Today marks the end of their first full week. Do they miss home? “Very much.” Do they have any doubts about their decision to come here? “No. Our dream is to perform.”

Flung to the highest reaches of the gymnasium, Luo Xu rolls feet first into a double backward somersault. Like clockwork she goes through her motions, folding arms over chest, arching her back like a seal and generally transforming herself into a sophisticated projectile, a sort of boomerang shot vertically.

What does a little girl feel at a moment like this? According to Luo, not very much. Her stomach is not churning. She does not feel dizzy. She is not afraid. And there is nothing on her mind. She is just turning somersaults. That is her thing, what she does best, and the coaches picked up on it right away. Every kid at the Shanghai Circus School turns somersaults, of course – a good hour’s worth, in every imaginable variation, every morning (before breakfast, thankfully) of every day. But there is something special about the way Luo does them, something her coaches can see but not necessarily express (“She has good reactions,” says one, rather cryptically), that recommends her in particular for the flying trapeze. It does not really matter whether she likes turning somersaults (though fortunately she does not mind it); it is simply her specialty. Every kid has a specialty. Every body has its purpose. It is up to the coaches to discover it.

Seen from the floor, Luo’s flight happens so fast it is nothing but a blur. But for Luo, it is not happening fast at all. Nor is it happening slowly. It is happening at precisely the speed of a double backward somersault. She knows where she is and what she is doing every step of the way. As she emerges from the second flip, her arms unfold again and she assumes a backward diving position. Her feet swing over, her head rolls under, and looking forward (or rather, upside-down and backward), she sees Zhen Liu approaching rapidly. Zhen is Luo’s catcher. Another big boy, also 16, also very kind, he rides on a swing from which he hangs by his knees, building great speed and arriving at just the right time, his strong arms ready to grasp her.

Luo reaches out.

The practice of acrobatics in China dates to the Stone Age. Scholars associate its origins with life on the farm – with tool play and the performing of chores, with harvest rituals and festivals, and with the ample time for practice afforded by long winter months. When and how acrobatics made the leap from peasant rite to performing art is not exactly clear, but records show that, by 1OBBC, Emperor Wu Di of the Han Dynasty was staging acrobatic performances for the entertainment of foreign dignitaries (thus establishing a diplomatic role for acrobatics that would one day be revived by Chairman Mao). Royal patronage would continue for a thousand years, until the demise of the Tang Dynasty in 907 brought with it a fall from imperial grace for acrobats. Supplanted at court by opera and the literary arts, deemed uncouth and even vulgar, acrobatics took to the streets (where, as courtly entertainment, it had been forbidden from playing). It has been an art for the masses ever since.

The next thousand years offer scant documentation of acrobatics. Like any other popular art, it was entertainment by illiterates for illiterates. To a large extent, its history has been carried along in the bodies of those who practiced it, transmitted from older to younger ones over the centuries. Countless stunts have been conceived and fostered and handed down by countless unknown, unremembered innovators. Countless others have been lost – many in the first half of the 20th century, when acrobats, like the poverty-stricken masses to whom they played, went starving.

The kids in this pink cube would never be here today if not for the 1949 revolution. Indeed, the art of acrobatics in China might well have been lost to the ages without the patronage of the Communist Party. As a homegrown art, as a people’s art, scorned by the upper classes, long suffering under the “cruel oppression of imperialists, bureaucratic capitalists and feudal landlords” (as the director of the China acrobatics troupe once observed), acrobatics was ideologically sound. With Mao’s blessing, it was elevated to a national symbol at the dawn of the People’s Republic. Eventually, every province, county and municipality in China would have its own troupe. Acrobats travelled far and wide – to factories, schools and mines, and deep into the countryside – to entertain the people. And with a billion of them to entertain, acrobats were in high demand. To join their ranks was a sure sign of status in the People’s Republic (they are officially “national treasures”) and a source of relative security and wealth. Something any parents might want for their child. Something any child might aspire to.

But times are changing once again for acrobatics. The students of the Shanghai Circus School belong, statistically at least, to yet another New China. On the other side of the school fence, there are kids their own age on the fast track to university, to jobs in business, finance and technology, to incomes and luxuries and forms of entertainment a previous generation could not have dreamed of. The older ones, the kids in their 20s, may remember acrobatics as the stuff their parents were stuck with, the state’s idea of fun. For the younger ones, though, acrobatics is not even on the map. The audience for Chinese acrobats, internally at least, would seem to be drying up.

Luo catches hold of Zhen’s wrists. Zhen catches hold of Luo’s wrists. One does not catch the other – they both catch each other. To an untrained observer, the precision with which they meet, hurtling towards each other at such speeds, from such unlikely angles, so high above the ground, is unfathomable. To their coaches, though, it is not such a great connect at all. For one thing, their faces almost smack. It is only Zhen’s strong arms that hold off a collision.

Hanging from his swing, his body long and straight, Zhen becomes a pendulum now. Luo, legs together, toes pointed like a ballerina’s, is the pendulum bob. Swinging through the lowest point of her arc, the halfway mark of her ride, her body begins to bow. As she starts to lift again, she sends a wave from torso to toes, much as a fish ripples its middle, to gain in speed. At about the moment she is parallel with the floor, Zhen releases her.

Luo’s feet keep rising as she flies. Her back bows further. Her head swings under. Her arms fold over her chest. She becomes the projectile again, the vertical boomerang, shooting almost to the ceiling of the hall. One backward somersault – no fear, no fun, no thoughts. Two backward somersaults – no fear, no fun, no thoughts. Then out come her arms again, and there is Yao Ting Li. Yet another big boy, he is poised on his perch, his strong arms waiting to catch her.

Luo reaches out.

The basic salary of an acrobat with the Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe, one of the most prestigious troupes in China and the one to which most graduates of the Shanghai Circus School are channelled, is around $200 a month. That is not a bad income in the provinces, but in Shanghai it will not get you far. There are some performers who make twice as much money or more (a handful of superstars earn over a thousand a month), and there are some who get picked up by the Cirque du Soleil and other well-paying international acts, but the vast majority of acrobats can expect to earn middle to low wages for the whole of their careers, which tend to be rather short anyway. And if demand for acrobats in China continues to dwindle, the students in the pink cube will be worse off, not better, than the professionals today – that is just the way it is with capitalism.

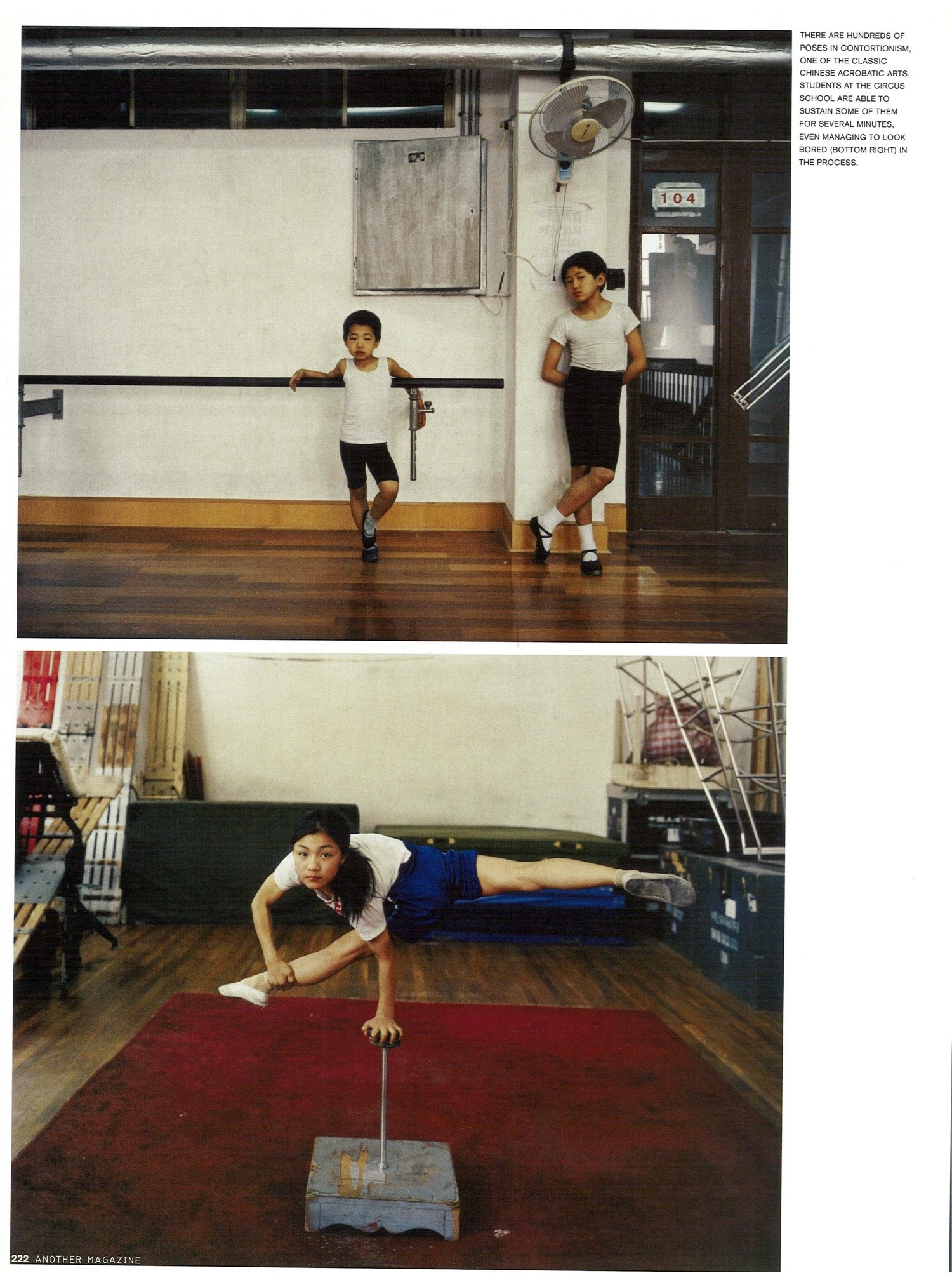

None of this is much on the minds of the students in the cube, however. They are rather absorbed in their balancing and contorting and their double backward somersaults. Fortunately for them, though, there is someone to think about their futures and that of their vocation. There is Principal Cheng. Ringmaster, literally and figuratively, of the circus that surrounds him, he is standing in the middle of the gymnasium just now, talking on his mobile phone. A burly man of 53, Principal Cheng knows a lot about acrobatics – he began his trapeze career at eight – but he has also learned a thing or two about the world. In 1984, as China began tentatively opening its doors, Hai Bao Cheng was the first acrobat to be sent to compete in a foreign competition (the prestigious Monte Carlo Acrobatic Festival, from which he returned with top prize). Later, he spent a year travelling the United States (all 50 of them, he notes) with the Ling-Ling Circus. When his illustrious career finally concluded (he was in his mid-40s, rather late for an acrobat), he was a natural to lead the Shanghai Circus School. As it happens, he is leading it into the future.

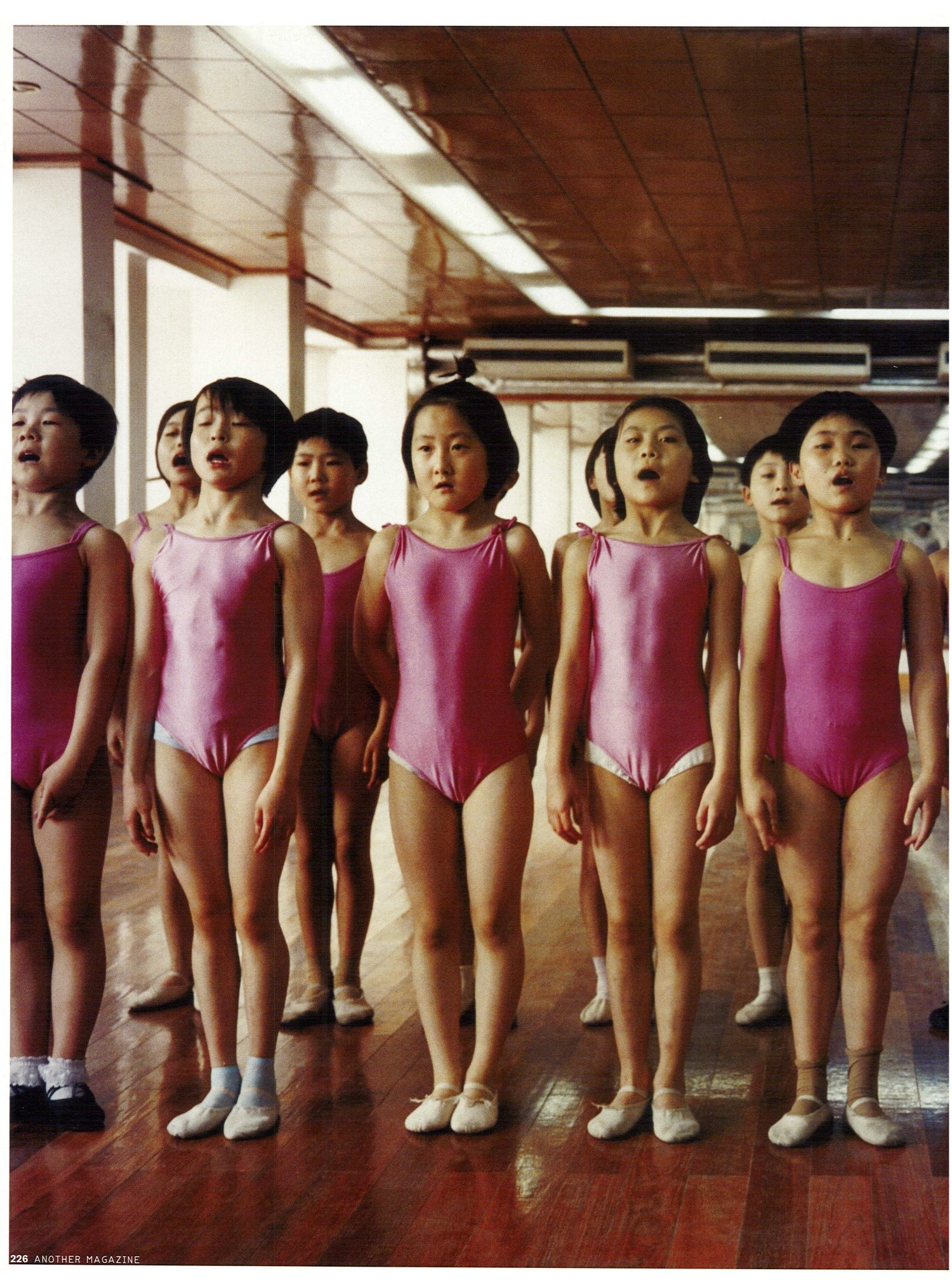

lt is hard to overstate the revolutionary nature of Principal Cheng’s programme. Acrobatic results are his mandate, and he is delivering them (he has sent his own students to Monte Carlo for the past five years, and every year they have won top prize). What is revolutionary is the way he delivers them not by turning his charges in to acrobatic robots but by giving them an education. The Shanghai Circus School is a certified middle school; completion of its seven-year programme results in a basic academic degree. After a full day of training (about eight hours, with a few short breaks), students shower, put on school clothes and sit down in classrooms for three to four hours of lessons (maths, sciences, Chinese, English, computers and more) with certified middle school teachers. This is a vast improvement over the education young acrobats received in Principal Cheng’s own day, when they were plucked out of elementary school and turned over to the local acrobatic troupe. But it is just part of Principal Cheng’s master plan – he recently put forth a proposal to the local government to develop the Shanghai Circus School into an institution of higher learning.

lt is Principal Cheng’s conviction, uttered almost the moment you meet him, that a solid educational foundation makes for a better acrobat. But underlying this may be an even stronger, unspoken conviction, grounded on the love he feels for his charges and his art, that acrobats must have options. Options in case of injury. In case of a change of heart. And options because, no matter how great an acrobat you are, your professional days are numbered. You start losing flexibility in your 20s. Your body puts on weight more readily. Beauty fades. By 40, what is left? Back in the days of communism, there was at least the state to count on. But today? To be consigned to a dwindling government pension as Shanghai booms all around you, to be left behind and forgotten – that is the future of an acrobat who has no options.

Thud. This is the sound Luo’s body makes as it hits the mattress of the safety net. A rather loud thud as thuds go, it would have been louder still if Luo did not know how to fall. But falling is a key part of her acrobatic training, and Luo is something of an expert at it. Done well, it can be as artful as any stunt. Luo herself falls as beautifully as a leaf.

When her body bounces up from the initial impact of the fall, Luo springs into sitting position. She is not bewildered or confused. She knows exactly what just happened and why. Standing up, she claps her talcum-powdered hands against her thighs and inspects herself for damage. Sometimes she gets rope burns from her safety cord, unsightly big ones on her arms and legs, but this time she is fine.

Luo’s coaches, who are seated just in front of where she fell, hardly pay her notice. They are too busy shouting at the boys. Not that Luo requires any attention – she simply does what she must do. She trudges across the mattress, clambers up the safety net, grabs hold of the rope ladder and starts to climb. lt takes a while to reach the top, but when she does, Zhi Fei is there. He flashes a smile, practically unnoticeable from the ground, and lifts her to her perch, her aerie, the place she spends the better part of every day. Luo is back in her element now. Ready to fly again.

To stand inside the cube and watch the students practice may be to glimpse another world, but it is just a glimpse you get, and glimpses can be misleading. You might notice, for example, how serious the students are and assume their lives are joyless. You might see the pain in their grimacing red faces as they practice their handstands (ten minutes on both hands, two minutes on the right hand, two minutes on the left, then 50 handstand push-ups), and wonder if this is cruelty. You might see Luo falling 20 metres and wonder if this is safe.

So it is a measure of Principal Cheng’s openness that he allowed a writer and photographer from a distant country to have a glimpse into this universe. And it is a measure of his wisdom that he allowed us so much more. In no uncertain terms, he offered unfettered access to his school. And the world we discovered was infinitely richer and more beautiful than a few hours in the gym could ever reveal. For as it turns out, the real magic of the Shanghai Circus School happens behind the scenes. lt happens between people.

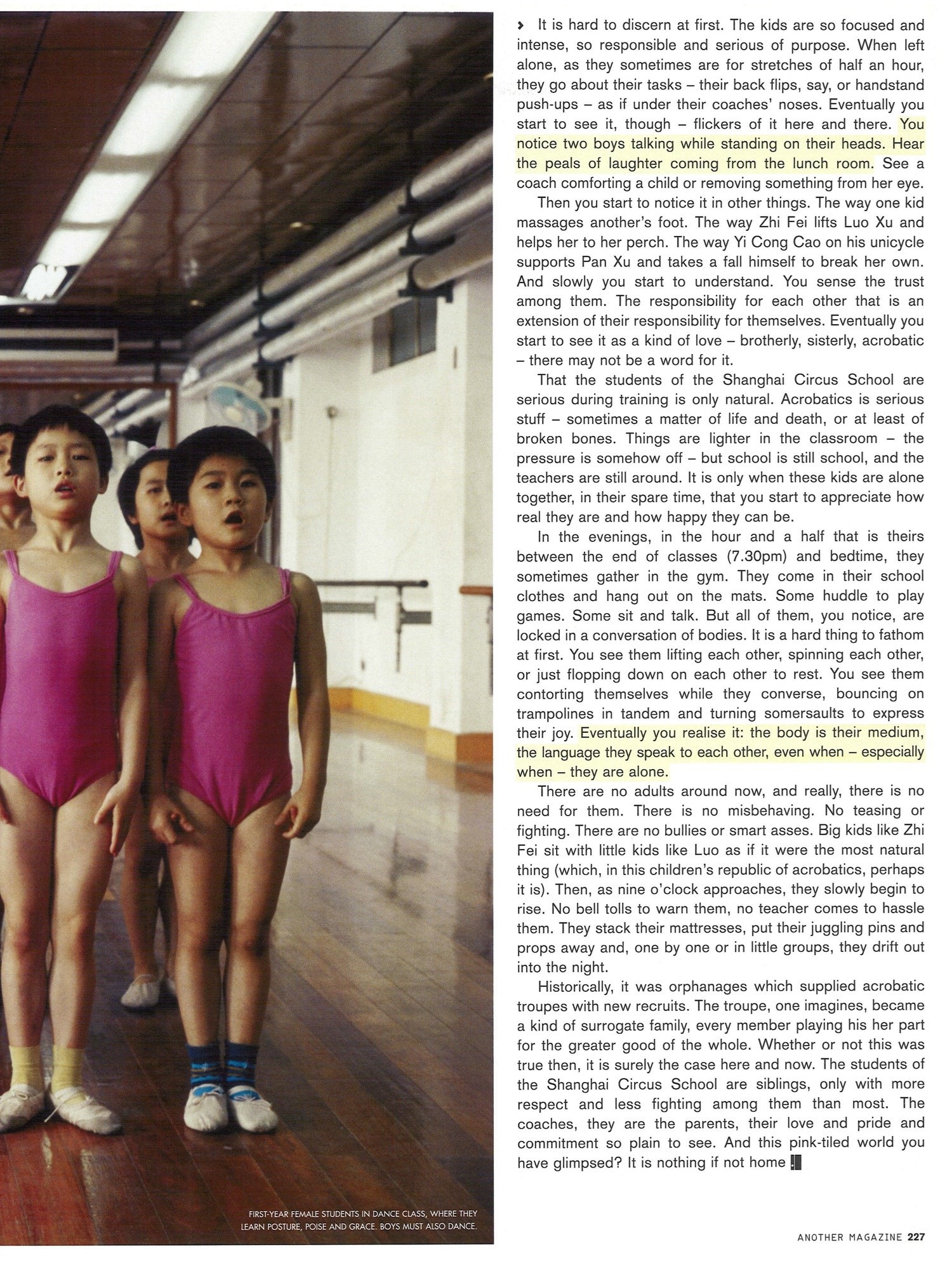

lt is hard to discern at first. The kids are so focused and intense, so responsible and serious of purpose. When left alone, as they sometimes are for stretches of half an hour, they go about their tasks – their back flips, say, or handstand push-ups – as if under their coaches’ noses. Eventually you start to see it, though – flickers of it here and there. You notice two boys talking while standing on their heads. Hear the peals of laughter coming from the lunch room. See a coach comforting a child or removing something from her eye.

Then you start to notice it in other things. The way one kid massages another’s foot. The way Zhi Fei lifts Luo Xu and helps her to her perch. The way Yi Cong Cao on his unicycle supports Pan Xu and takes a fall himself to break her own. And slowly you start to understand. You sense the trust among them. The responsibility for each other that is an extension of their responsibility for themselves. Eventually you start to see it as a kind of love – brotherly, sisterly, acrobatic – there may not be a word for it.

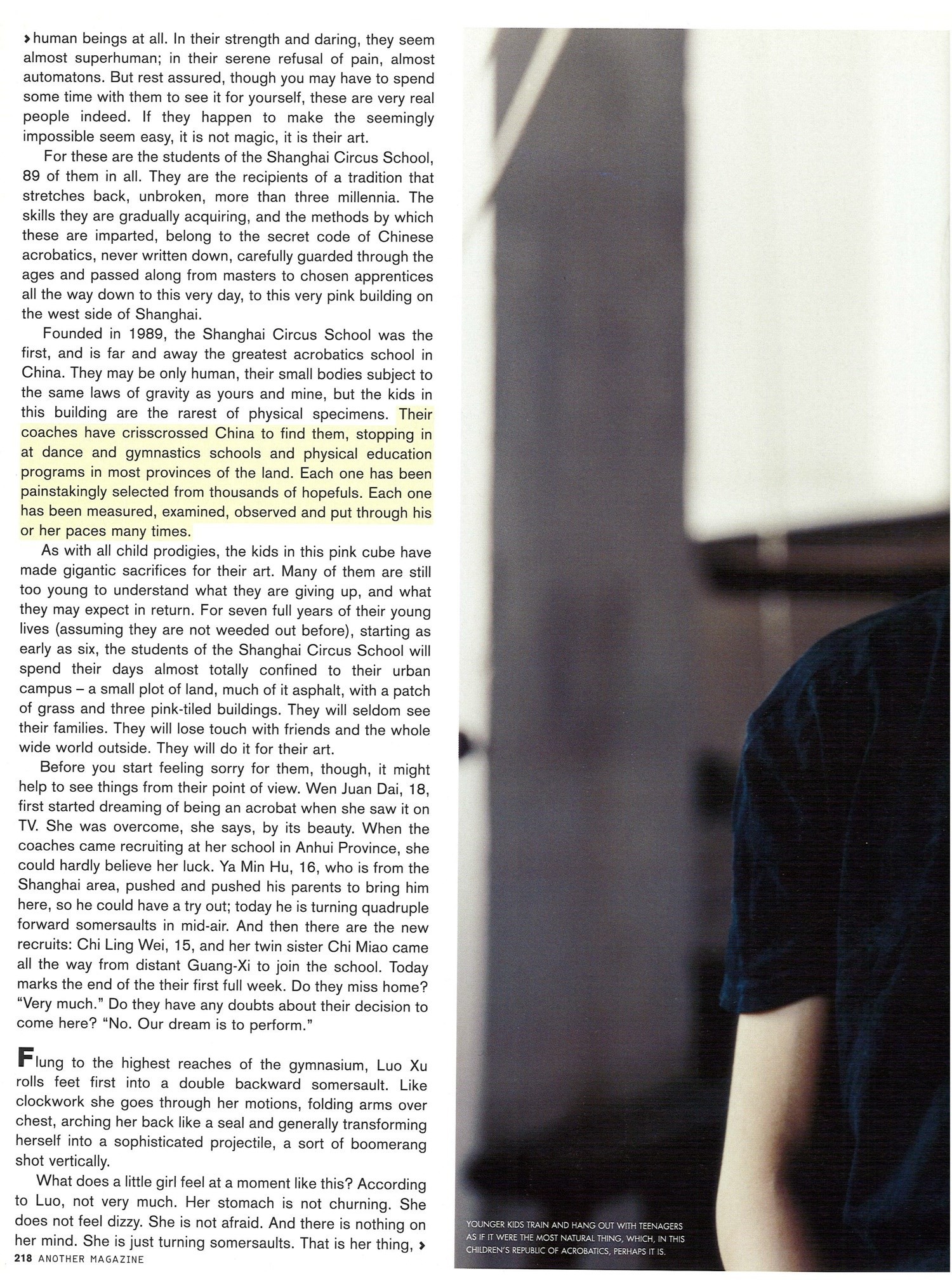

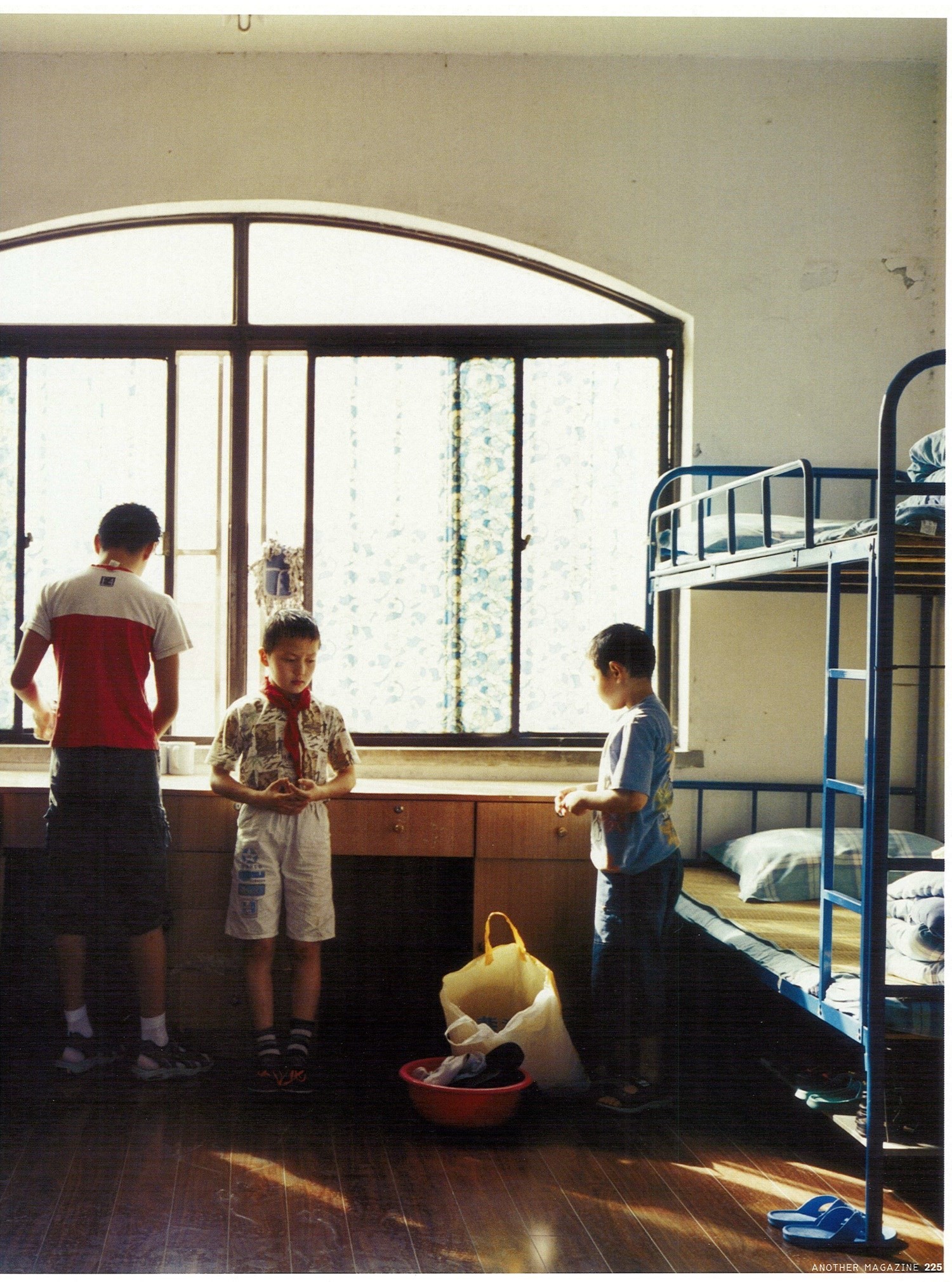

That the students of the Shanghai Circus School are serious during training is only natural. Acrobatics is serious stuff – sometimes a matter of life and death, or at least of broken bones. Things are lighter in the classroom – the pressure is somehow off – but school is still school, and the teachers are still around. lt is only when these kids are alone together, in their spare time, that you start to appreciate how real they are and how happy they can be.

In the evenings, in the hour and a half that is theirs between the end of classes (7.30pm) and bedtime, they sometimes gather in the gym. They come in their school clothes and hang out on the mats. Some huddle to play games. Some sit and talk. But all of them, you notice, are locked in a conversation of bodies. lt is a hard thing to fathom at first. You see them lifting each other, spinning each other, or just flopping down on each other to rest. You see them contorting themselves while they converse, bouncing on trampolines in tandem and turning somersaults to express their joy. Eventually you realise it: the body is their medium, the language they speak to each other, even when – especially when – they are alone.

There are no adults around now, and really, there is no need for them. There is no misbehaving. No teasing or fighting. There are no bullies or smart asses. Big kids like Zhi Fei sit with little kids like Luo as if it were the most natural thing (which, in this children’s republic of acrobatics, perhaps it is). Then, as nine o’clock approaches, they slowly begin to rise. No bell tolls to warn them, no teacher comes to hassle them. They stack their mattresses, put their juggling pins and props away and, one by one or in little groups, they drift out into the night.

Historically, it was orphanages which supplied acrobatic troupes with new recruits. The troupe, one imagines, became a kind of surrogate family, every member playing his her part for the greater good of the whole. Whether or not this was true then, it is surely the case here and now. The students of the Shanghai Circus School are siblings, only with more respect and less fighting among them than most. The coaches, they are the parents, their love and pride and commitment so plain to see. And this pink-tiled world you have glimpsed? It is nothing if not home.

This article originally featured in the Autumn/Winter 2004 issue of AnOther Magazine.

Photographic assistant: Monia Lippi.