A look back at some of the foremost artists of the Black Power Movement in the USA, dating from 1963 to 1983, and how their work has galvanised a generation that followed in their footsteps

In July 2017, Tate Modern staged the exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power. Curated by Zoe Whitley, who is currently director of London’s Chisenhale Gallery, and Mark Godfrey, Soul of a Nation looked back to 1963, and how over 60 artists in America responded to the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power movement which followed. Today, protests continue in cities around the world – the biggest since those that took place in the 1960s – in response to the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a white police officer in Minneapolis. The struggle for racial equality continues, and the artists and artworks featured in the 2017 exhibition are as relevant as ever.

The peak of the Black Power Movement in the US roughly dates from 1965 to 1985; Soul of a Nation largely covered this period, extending a few years either side. The raised fist is a symbol that is widely known and associated with Black Power today; in 1968, the prolific artist Elizabeth Catlett produced a large mahogany fist in a sculpture entitled Black Unity, with two faces carved into the back of the hand. “I have always wanted my art to service my people – to reflect us, to relate to us, to stimulate us, to make us aware of our potential,” Catlett once said. Her work, in sculpture, woodcuts and linocuts, continually addressed feminism and civil rights (this particular intersection interested her peers Betye Saar and Kay Brown too). Figurative paintings by Catlett’s former husband, Charles White, also depicted the realities of being a black American in the 20th century. “I have no use for artists who try to divorce themselves from the struggle,” White once said.

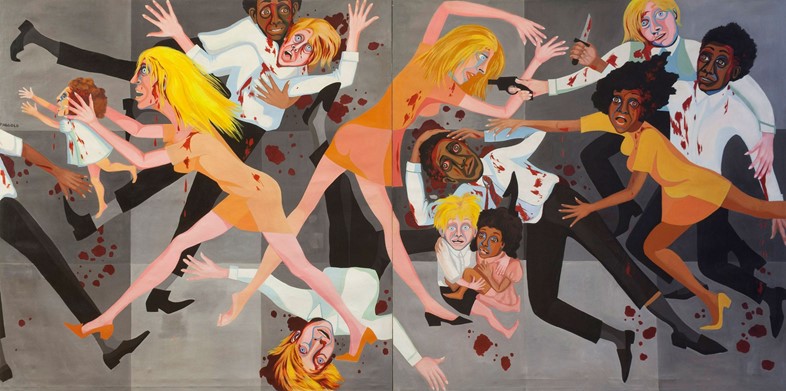

In painting, the work of Faith Ringgold and Barkley L Hendricks also proved pioneering in the late 1960s. According to Ringgold, who grew up in Harlem near Langston Hughes and cites writers James Baldwin and Amiri Baraka as inspirations, “it was the 1960s and I could not act like everything was OK. I couldn’t paint landscapes in the 1960s – there was too much going on.” In a searing work from her American People Series, Die, Ringgold depicts a violent race riot, populated with black and white men, women and children alike. The artist confronted the unrest that was occurring during this time across America, and in another piece from the series, The Flag Is Bleeding, figures are seen between the stars and stripes of the country’s flag, which are dripping with blood. Benny Andrews’ 1969 painting Did the Bear Sit Under the Tree? similarly incorporates American iconography to highlight inequalities.

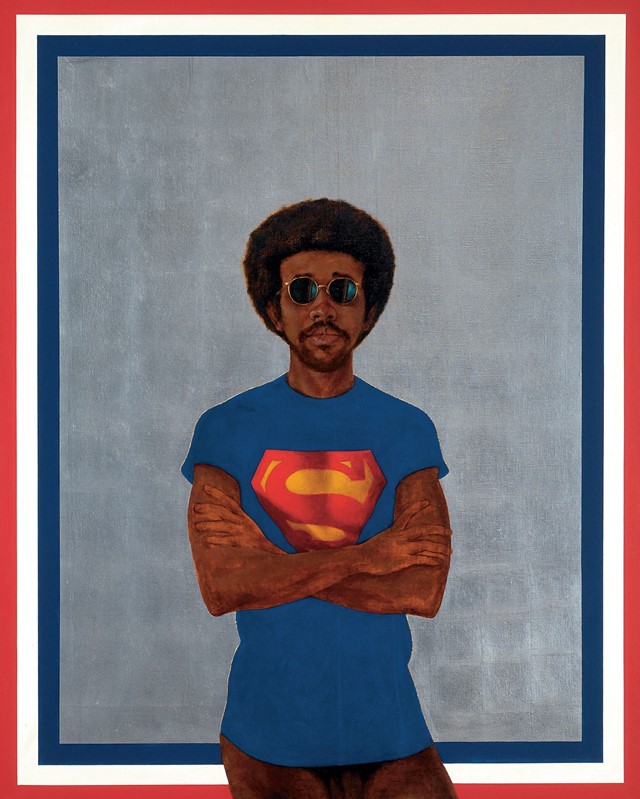

While some artists did not set out to make overtly political work, by carving out space for themselves as artists and subjects their pieces became galvanising. Hendricks’ chosen genre was portraiture: painting himself, his friends, family and peers in his life-size portraits, the artist was addressing the lack of black subjects in celebrated art history. “My paintings were about people that were part of my life,” he said in 2016. “If they were political, it’s because they were a reflection of the culture we were drowning in.” Hendricks was part of a generation not used to seeing themselves represented in art, his exalting portraits attempted to rectify this for those to come.

Alongside artists like White, Charles Alston and Romare Bearden, Hendricks depicted black life. Alston and Bearden were founding members, alongside Norman Lewis and Hale Woodruff, of the collective Spiral in 1963. The group of 15 artists met weekly for two years, and their core focus was how art could and should respond to, and depict, the struggle for civil rights in America. Collectives proved powerful forces during the Black Power Movement: in Chicago, AfriCOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists) was founded by Jeff Donaldson, Wadsworth Jarrell, Jae Jarrell, Barbara Jones-Hogu, and Gerald Williams, whose work spanned fashion and art. “Theirs is activist work not just because of its political content, or because its Pop energy makes you want to get up and dance, but also because it’s so clearly designed, with its polish and flair, to infiltrate mainstream institutional space,” wrote Holland Cotter in The New York Times in 2018.

Elsewhere, the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition was formed in 1969 in response to an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art entitled Harlem On My Mind, which traced the artistic history of the New York neighbourhood back to 1900 but did not include any black artists. The BECC protested against the exhibition, and worked for greater representation in the art world. Many predominant creatives came from Harlem, and drew on life there for their work; in 1955, photographer Roy DeCarava and writer Langston Hughes collaborated on the celebrated book The Sweet Flypaper of Life, a poem of words and photographs telling everyday stories of living in Harlem. Many artists during this time would exhibit their work among black communities and create public art, seeking new audiences to galvanise with their work by showing how art could be akin to activism. “The ghetto itself is the gallery,” said artist and culture minister of the Black Panther Party Emory Douglas.

“There’s a double meaning we’re playing with here. For people interested in abstract artists you might think of Cy Twombly or Robert Rauschenberg but we’re showing how African American artists like William T. Williams and Sam Gilliam were important to that movement too,” Whitley told AnOther as Soul of a Nation opened in London (it was staged in New York in 2018), speaking of how the exhibition also featured black artists whose work and impact have been overlooked in the canon of 20th-century art. Williams’ late 1960s and 1970s work was key to American Abstractionism, yet his is not a household name. The artist, who is based in New York, made colourful, free-flowing, shape-filled pieces during this time, and became the inaugural artist-in-residence at Studio Museum in Harlem, a programme which he also proposed to the gallery and still runs successfully to this day.

It was this generation of revolutionary artists, among many others, who paved the way for today’s creatives to make work just as pioneering and pertinent. For photographers like Carrie Mae Weems: in turn, Weems’ seminal 1989–90 photographs The Kitchen Table Series has proved hugely influential for the image-makers who have come after her, who centre black communities and stories in their images. Think Deana Lawson, Tyler Mitchell, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Liz Johnson Artur and more. In the realm of painting, Kerry James Marshall was taught by Charles White. Marshall has described the influence of the Black Power Movement on his practice, and uses his paintings to address ideas around race and subsequent social justice issues. “Under Charles White’s influence I always knew that I wanted to make work that was about something: history, culture, politics, social issues,” he said. “It was just a matter of mastering the skills to actually do it.”

Contemporary performance artist and sculptor Nick Cave has described the direct influence of Steve, a 1976 portrait by Barkley Hendricks, on his artistic career: “It was really epic to see this urban black male existing in this space, owning it, projecting upward. I think a lot about my work in that same way.” There are echoes of Hendricks’ heroes in the uplifting portraiture of Kehinde Wiley, the first black artist, alongside Amy Sherald, to paint an official portrait (of former president Barack Obama; Sherald painted Michelle) for the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. Look as well to the spellbinding water-based portraits of Calida Garcia Rawles and the lyrical, complex worlds of Toyin Ojih Odutola. Here in the UK, British painter and writer Lynette Yiadom-Boakye presents similarly rich worlds and figures – her first major survey, Fly in League with the Night was due to open at Tate Britain in May of this year.

The fact that black communities have suffered – and continue to suffer – violence at the hands of white oppressors does not go unchecked by the artists of today, or those who came before. Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death is a 2016 film by the contemporary video artist and cinematographer Arthur Jafa. The film explores blackness as a creative force and an object of white brutality through layers of found footage – sometimes celebratory, sometimes harmful – of civil rights marches, police violence, NBA sports, twerking, speeches, music and more, oscillating between the everyday and the extraordinary in its searing seven minutes. And this travels beyond art: the fashion designer Mowalola Ogunlesi famously painted bleeding bullet holes onto a series of garments for S/S20, describing that the motif “screams my lived experience as a black person”. “We are time after time seen as a walking target,” she said in response to criticism of the designs. In these works, and in countless others, is the power of art to uplift, showcase, describe and demonstrate the black experience – sometimes in uncomfortable but entirely necessary, vital ways.

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power was at Tate Modern, London, from July 12 – October 22, 2017, and at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, from September 14, 2018 – February 2, 2019. The exhibition opens at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, from June 27 – August 30, 2020.

See also: an ongoing list of ways to join the anti-racist fight; and practical things you can do to fight racism in the UK.