As an exhibition of Gordon Parks’ enduring works opens at Alison Jacques Gallery, a selection of the image-maker’s most enduring words on how photography can affect change

Gordon Parks was a prolific photographer, filmmaker, writer, poet, painter and composer. During his extensive career, he was a pioneer: in the 1950s he became the first black photographer on staff at Life magazine, where he would work for over 20 years; in 1969 with the release of The Learning Tree, Parks became the first black director to helm a Hollywood studio film (he also produced it, wrote the screenplay – an adaptation of his semi-autobiographical novel of the same name – and composed the film’s score); and his 1971 film Shaft is credited as the first blaxploitation movie. Over the course of his life, Parks wrote four autobiographies, among novels and poetry collections, the last of which was published in 2005, the year before he died at the age of 93.

Parks’ photography spanned documentary, fashion (for the pages of Vogue) and portraiture, with his photo stories for Life magazine becoming some of his most enduring. While at the magazine, he would direct his lens towards subjects like racial segregation and poverty – both of which he had experienced – knowing that they might make for difficult, but vital, stories. Recent years have seen publications and exhibitions honing in on Parks’ years as a self-taught photographer in the 1940s (The New Tide: Early Work 1940–1950) and his series of photographs for Life on crime in the United States (The Atmosphere of Crime, 1957).

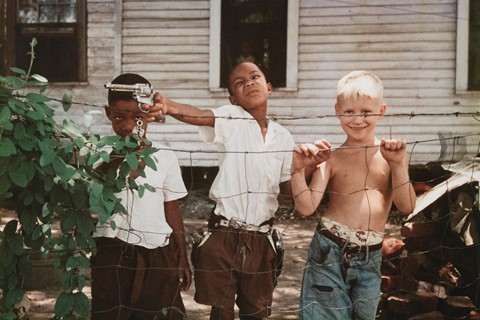

An exhibition opening today at Alison Jacques Gallery is entitled Gordon Parks: Part One, and showcases photographs from two of his stories for Life magazine: Segregation in the South (1956) and Black Muslims (1963). (Part Two will open later this year, focusing on Parks’ photographs of Muhammad Ali.) The former was photographed in Alabama, where Parks spent time with three families and captured their everyday lives amid the wider context of the burgeoning civil rights movement in America. For the latter, Parks spent months with core members of the Nation of Islam – Malcolm X, Elijah Muhammad, Ethel Sharrieff – as well as the group’s wider community. Parks wrote the accompanying article for Black Muslims, in which he reckoned with the movement on a personal and public level.

The report saw Parks reflect on his own life and career. “In fulfilling my professional and artistic ambitions in the White Man’s world, I had had to become completely involved in it,” Parks wrote. “At the beginning of my career I missed the soft, easy laughter of Harlem and the security of black friends around me … Many times I wondered whether my achievement was worth the loneliness I experienced, but now I realise the price was small. This same experience has taught me that there is nothing ignoble about a black man climbing from the troubled darkness on a white man’s ladder, providing he doesn’t forsake the others who, subsequently, must escape that same darkness.” Parks’ legacy continues today: through the Gordon Parks Foundation, fellowships are awarded to young black artists to create work in his same spirit of representation and social justice, and 2020’s fellows are Tyler Mitchell and Nina Chanel Abney. As Gordon Parks: Part One opens in London, a selection of Parks’ quotes on the power of photography.

- “Pictures I’ve made that have become the most important pictures, were pictures that I wished I never had to take – of people who were impoverished, people in need – and I suppose that I pointed my camera mostly at people who needed someone to say something for them. They couldn’t speak for themselves.”

- “The world must see the tragedy of poverty as it is, and feel all its drama. Everyone must face the problems of humanity. My way of facing these issues is through photography. It is important because it can show, without needing words, everything that is wrong and can be improved.”

- “I’d become sort of involved in things that were happening to people. No matter what colour they be, whether they be Indians, or Negroes, the poor white person or anyone who was I thought more or less getting a bad shake. I thought I had the instinct toward championing the cause.”

- “I suffered first as a child from discrimination, poverty ... So I think it was a natural follow from that that I should use my camera to speak for people who are unable to speak for themselves.”

- “I feel it is the heart, not the eye, that should determine the content of the photograph. What the eye sees is its own. What the heart can perceive is a very different matter.”

- “I picked up a camera because it was my choice of weapons against what I hated most about the universe: racism, intolerance, poverty. I could have just as easily picked up a knife or a gun, like many of my childhood friends did ... most of whom were murdered or put in prison ... but I chose not to go that way. I felt that I could somehow subdue these evils by doing something beautiful that people recognise me by, and thus make a whole different life for myself, which has proved to be so.”

- “I must attempt to transcend the limitations of my own experience by sharing, as deeply as possible, the problems of those I photograph.”

- “You have a 45mm automatic pistol on your lap, and I have a 35mm camera on my lap, and my weapon is just as powerful as yours.”

- “I don’t know that I was any better equipped. I probably ... in some instances I was, more than probably the white photographers because of an emotional something that probably I was closer to or akin to which has certainly been in my favour since. Some of those Negro stories that I’ve done for Life and Standard Oil and other places have dealt with poverty, dealt with the emotional aspect of everyday living, because my own life was packed, early life, was packed with so much of it.”

- “What the camera had to do was expose the evils of racism, the evils of poverty, the discrimination and the bigotry, by showing the people who suffered most under it.”

Gordon Parks: Part One is at Alison Jacques Gallery from July 1 – August 1, 2020. Part Two will be open from September 1 – October 1, 2020.