Legendary image-maker Joel Meyerowitz shares his advice for aspiring photographers, as his new book How I Make Photographs is published

When Joel Meyerowitz met Robert Frank on the set of a photo shoot one day in 1962, he had an epiphany that changed his life forever. Meyerowitz, then 24 and working as art director at a New York advertising agency, positioned himself behind the Swiss photographer and began to discern Frank’s unique and exquisite ability to capture fragmentary images of beauty as they appeared.

“I kept hearing the click [of his Leica] and seeing the frozen moment as it dissolved into the continuation of reality,” Meyerowitz tells AnOther from his home in Italy. “After a while I began to see those frozen moments happened every time he clicked so he must have been anticipating the richness of the moment in a very ordinary situation.”

After finishing the job, Meyerowitz stepped onto the street and discovered a world full of mesmerising happenings he wanted to capture for himself. He walked 30 blocks back to the office then promptly quit his job. Meyerowitz had no photography training, not even a camera of his own, but he knew exactly what he had to do to make his way in the world.

From that single leap of faith, an extraordinary career was born, one that has made Meyerowitz into one of the most celebrated street photographers of our time. This month Meyerowitz releases How I Make Photographs, an intimate volume filled with warmth, wit and wisdom gleaned from his extraordinary career in photography. Here, Meyerowtiz shares five tips for those who seek to record magical scenes of everyday life as it unfolds before our very eyes.

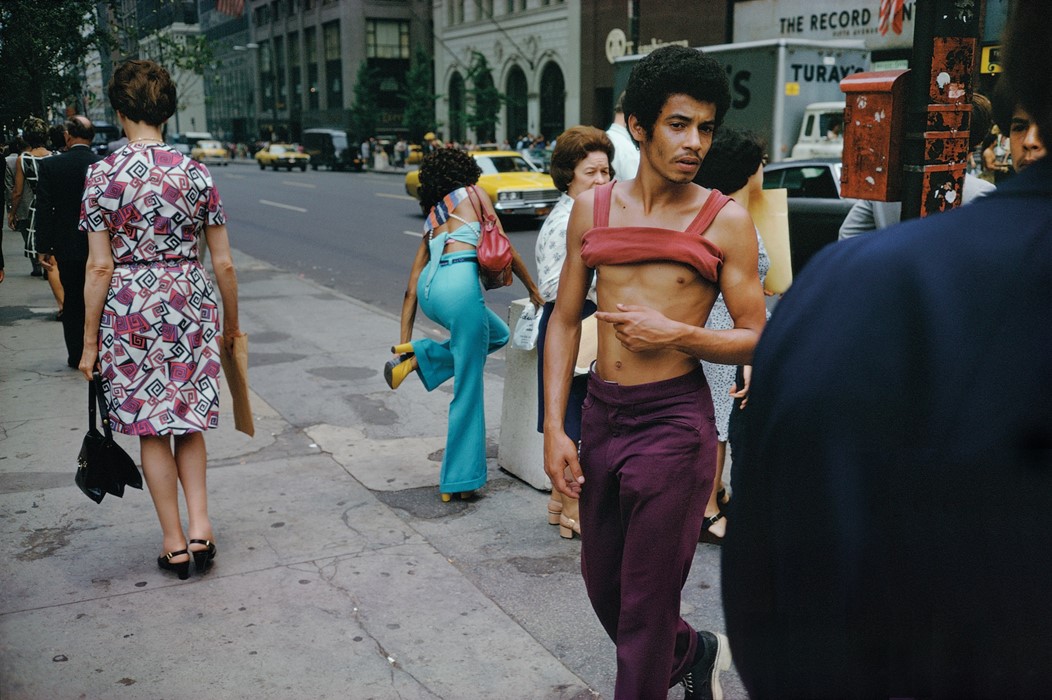

1. Discover your identity as an artist

“After the shoot with Robert Frank was over, I went out onto the street. It was full of these happenings everywhere I turned. They were the most ordinary things – somebody carrying their laundry in two sacks or someone pushing the baby carriage – all these little passings that happen to us all the time that we barely take note of. Suddenly each and every one of them seemed to me to be a heart-stopping moment. I thought, ‘if I had a camera – that’s it for me’. If I learned to capture these things that I might find out more about who I am, therefore my identity.”

2. Trust your instincts

“I never second guess myself. If an impulse comes up for me, a flicker of something in front of me that draws my attention to it, the camera is already rising in my hand to my eye to make a photograph of it because I don’t care about wasting film. I don’t want to lose the moment. I never hesitate because every hesitation is the loss of something emblematic of a recognition. I feel like anytime someone raises the camera and pauses on ‘should I or shouldn’t I?’ they are in the dilemma – and that’s a life dilemma.”

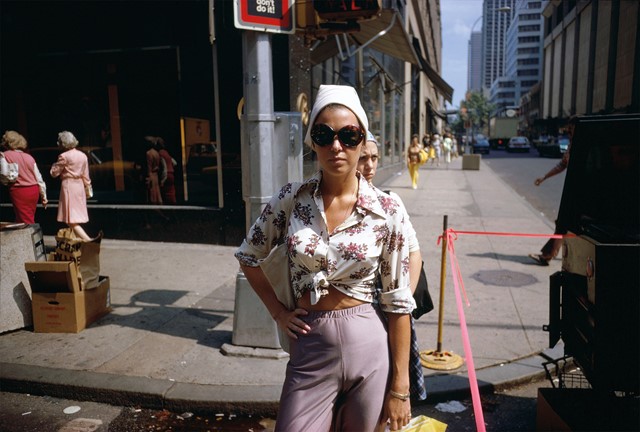

3. Give yourself to the moment

“I knew that I had to spend myself freely. If the nuance of something touches me but not knowing why, I reach for it and I’ll analyse it later. In the moment I want to be as alive and connected and fluid as possible. These are essential states of being for anyone who is trying to understand who they are. We have two choices: to be lost and always in search of something or to feel like you are in possession of some understanding of your inner potential. I’m all for integration. I want to know through these images more about myself.”

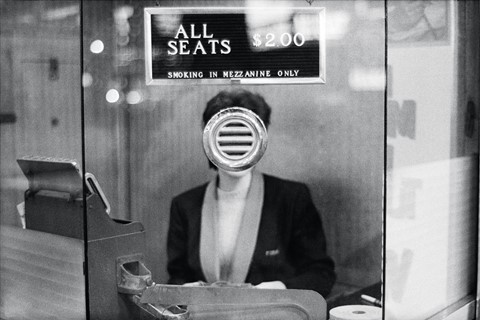

4. Become invisible

“When I started I was shy and didn’t know how to handle myself on the street. How do you get close to people? How do you make yourself invisible? In 1963, I was at the St. Patrick’s Day Parade with Tony Ray-Jones, and we saw Henri Cartier-Bresson working the street. He was like a ballet dancer, twisting and turning; people weren’t really seeing him and he was right in their faces. That gave us a sense of how elegant it could be. As I began to do it more and more, I developed of body gestures that allowed me to be in the moment but not altering the reality of the space.”

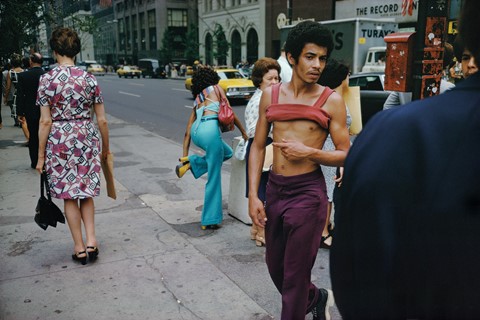

5. Become fluent in body language

“It’s a little like semiotics: it’s reading the signals and signs. If you’re looking at crowds, you read their projected inner thoughts through their physicality. You begin anticipate what they are going to do next, which makes you even faster when action happens they way you thought – your camera is now up and ready. By doing that you feel your capacities enlarged and have more possession of the space you are working in. It’s not something you think about beforehand, it’s something you grow into like language itself. We absorb the language and employ it in lyrical, dramatic, poignant ways to become capable of expressing ourselves.”

Joel Meyerowitz: How I Make Photographs is published by Laurence King.