DISKO, Miksys’ decade-long series exploring discos in Lithuania, is currently on show in Open Eye Gallery’s The Time We Call Our Own, an exhibition about the power and importance of nightlife

In 2020, nightlife has been threatened like never before. Lockdowns across the world have forced clubs, bars and other venues to shut their doors with no indication of when they might open again. It makes for a poignant time to stage The Time We Call Our Own, a new exhibition at Liverpool’s Open Eye Gallery, curated by Adam Murray, which looks at nightlife, its power and importance. Six photographers feature in the exhibition – Amelia Lonsdale, Andrew Miksys, Oliver Sieber, Dustin Thierry, Mirjam Wirz and Tobias Zielony – and each has explored the subcultures and communities that after-dark socialising can create, often most powerfully for otherwise marginalised people. At a time when this kind of freedom is called into question – whether by a pandemic or politics – nightlife feels more important than ever.

In 1998, Andrew Miksys received a Fulbright grant to photograph in Lithuania for a year, and there he stumbled upon a project that he would continue for the next ten. Returning to the country where his father was born, Miksys – who grew up in Seattle and now lives in Vilnius, Lithuania – travelled around by car and stopped in small towns and villages. DISKO was born after he spotted “some kids carrying beer into a grey Soviet building” one day. “After that night, I ended up spending nearly ten years and many weekends travelling to village discos all over Lithuania,” he says. Making his way around a country in flux – at the time, Lithuania was post-USSR and pre-EU – Miksys found young people “hungry for change and looking for new experiences”. He published the book DISKO in 2013.

“It was a brief moment in time where it felt like something really unique was happening, but the places and people I photographed are gone forever,” he explains. Though he has no plans to return to DISKO, Miksys sees how a generation galvanised by nightlife and subcultures can be a powerful force: having photographed in Belarus, he’s now following the protests happening in the country after the recent rigged presidential election. “In the past ten years, the young people in Belarus definitely changed the nightlife and made it much more alternative – I’m sure the nightlife served as an incubator for new ideas that helped create the protests,” he says. “I encourage everyone to follow what’s going on in Belarus and help support the peaceful protests for democracy and fair elections – @highlightbelarus on Instagram has daily updates on events in English.”

As DISKO is exhibited in The Time We Call Our Own, Miksys tells the story behind the series, and reflects on nightlife’s past, present and future.

“Lithuania had been occupied as part of the Soviet Union since the end of the Second World War and regained its independence in 1991. When my father was a baby, my grandparents had fled Lithuania during the war on a horse and buggy. They eventually ended up in the United States. I came to Lithuania for the first time in the mid-90s to visit my relatives. When I got the Fulbright I bought a VW Golf and set off on road trips all over Lithuania. One day I ended up in a small town and saw some kids carrying beer into a grey Soviet building. I followed them and found the first disco for my DISKO project. It was an amazing room with dark brown wood panelling, vinyl red chairs, a disco ball, and a Lenin head on the wall. I was obsessed with the Lenin head and would pose people in front of it. The disco had the kind of atmosphere where time seems a little off. It’s the present, but it feels like the past, and the future is coming along fast. But for my photography, it felt perfect. Driving home that night I saw disco lights and kids gathering near cultural centres in other villages and small towns. I had no idea there were so many village discos.

“Lithuania in the 1990s had a very ‘anything is possible’ vibe. There was dramatic economic and social change. People were able to travel more freely and see things beyond their small towns and villages. Rural kids in particular were hungry for change and looking for new experiences. They moved to bigger cities or found ways to go abroad. All this was happening before Facebook and other [forms of] social media. The discos were the main places to gather and share new music from other countries and local music that was flourishing in a new democracy. The discos were packed. But when Lithuania joined the European Union in 2004, the disco kids finally had a chance to escape forever. I don’t want to make it sound like village life is terrible, but the border with Europe had been closed for 50 years during the Soviet Union and people wanted to see what other opportunities were out there. After 2005 the crowds at the discos started to go down and now most are closed.

“It’s kinda funny to hear what [the people I met] remember about being photographed. It must have been weird for a foreign guy with long hair to show up at their village disco. At first, I also couldn’t speak any Lithuanian. One girl who now lives in the UK told me I had photographed her on her 16th birthday and she has really fond memories of that night. I also stay in touch with DJ Playboy, a DJ from a small town – he welcomed me right away when I came to his disco. He now works in a hospital across the street from my apartment in Vilnius. Open Eye Gallery had all the artists make a soundtrack for their project and DJ Playboy helped me make mine with his favourite music from the 1990s and 2000s. It was great to get his list, since I can barely remember what was playing when I was photographing.

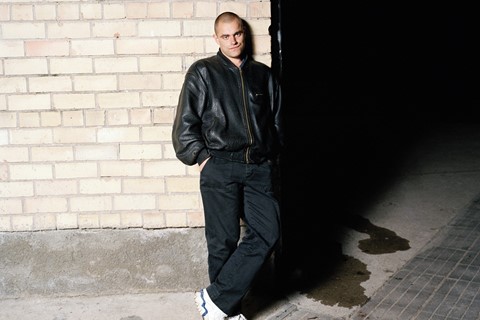

“I like the photograph of the girl wearing a cropped sweater, boots and mini skirt standing against a column with a room full of men in jeans and black leather jackets in the background. I was using a large, studio-style flash, but it didn’t have a modelling light and I couldn’t see what was going on behind her. It wasn’t until later, when I got the film back, that I saw the guys in the background. I like how she looks alone in her thoughts in the foreground with a whole other masculine reality going on behind her. In this disco a few of the guys in leather jackets politely instructed me to drink vodka with them before I started photographing. I understood I wouldn’t be able to photograph unless I sat at their table and did shots. But I like vodka. I passed the test and the guys were super-friendly and helped me photograph.

“I keep having a weird feeling that the kind of nightlife in my photographs is a relic of the past, something that might not return. Will there ever be small spaces filled with large groups of sweaty people, dancing, touching and enjoying close contact again? I feel somehow grateful that I was able to experience that kind of interaction before the world changed. I keep hearing that humans have short memories and everything will return once there is a vaccine. Let’s hope so. But maybe the internet, social media, and apps had a bigger impact on nightlife even before the pandemic? It seems like people were already more insular and connected online than in person.

“Maybe the most important part of the word nightlife is ‘night’? Somehow the dark opens up possibilities for different experiences and interactions. Maybe it’s some ancient human thing and we function differently at night and our senses are more alert. In my DISKO book I wrote about Lithuanian pagans who used to hold their midsummer solstice rituals at night. They would jump over fires while the young people would go into the forest to look for mythical magic fern blossoms. The fern blossoms didn’t really exist but the kids were alone in the forest without adult supervision and had a chance to meet each other at night. Kind of sounds like a disco, right? I like to imagine Lithuanian pagans inventing the first disco and using the full moon and stars as their disco ball.”

The Time We Call Our Own is at Open Eye Gallery, Liverpool until October 23 2020