Photographers Sunil Gupta and Nick Sethi use the camera as a compass on their journey through life, using it to create connections that allow them to explore the complex intersections of identity, family, race, migration, and sexuality in the East and the West. Transforming photography as a tool of liberation, their vivid portrait and documentary work fuses the personal and political into a mesmerising mélange of places and faces.

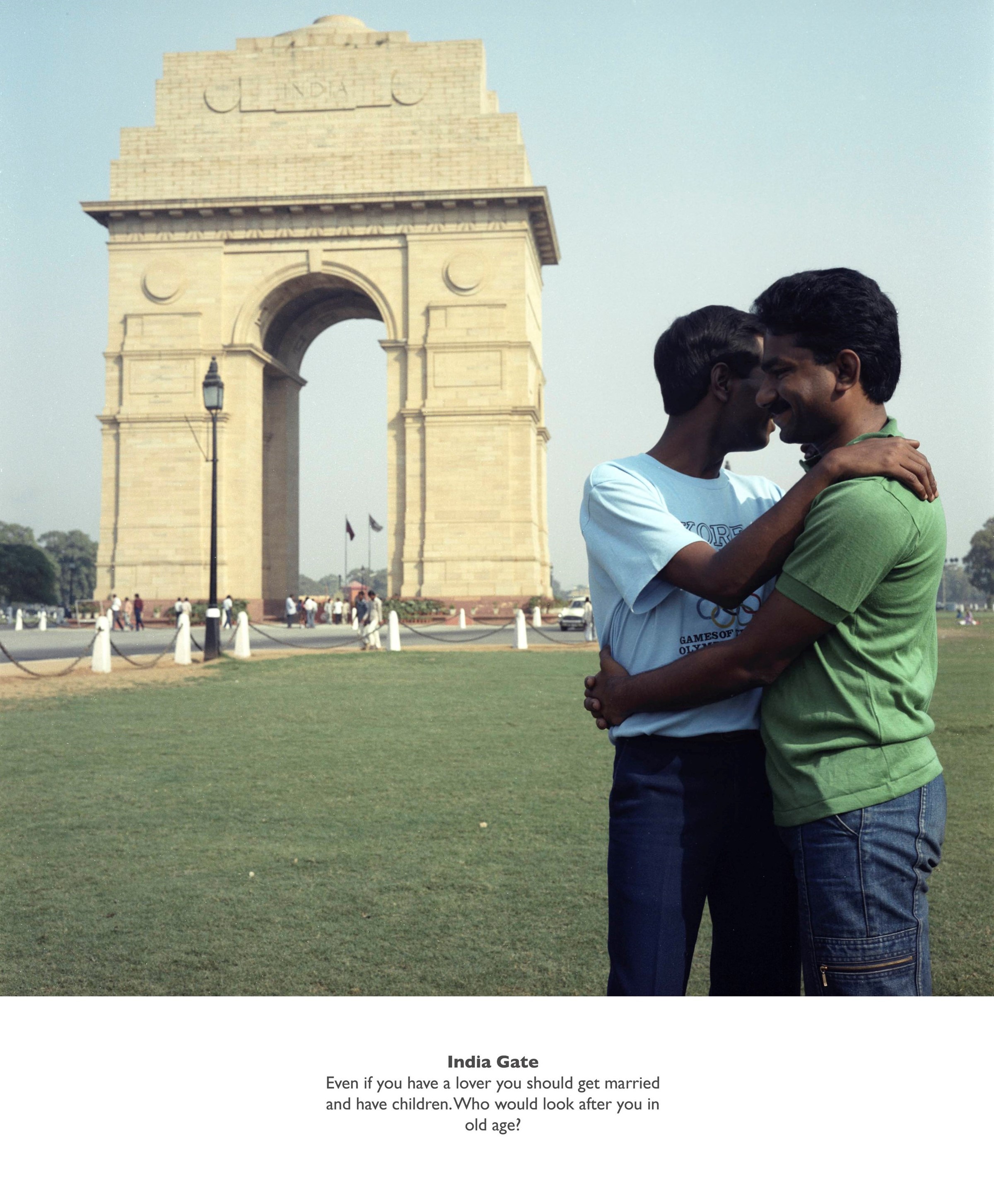

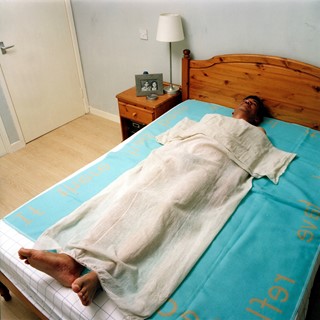

With the October 9 opening of From Here to Eternity. Sunil Gupta. A Retrospective and the publication of Lovers: Ten Years On (Stanley/Barker) coming on the heels of the landmark exhibition and catalogue Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography, Gupta’s work is being widely celebrated in his adopted home of London, nearly 40 years after the Delhi-born, Montreal-raised artist emigrated to the UK. Gupta’s retrospective will showcase works from 16 series over the past 45 years that reveal how he has used photography as a form of activism to address his experiences as a gay Indian man living with HIV, while also exploring ethical questions of documentation and representation that helped bring abut the formation of Autograph – the Association of Black Photographers, an organisation devoted to fighting discrimination in the UK.

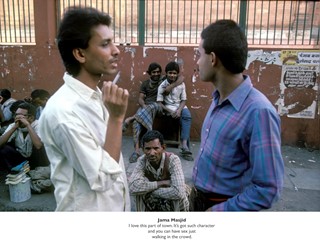

Sethi, a first-generation Indian-American, who is currently based in New York, also uses photography to connect and explore the space where empathy creates understanding beyond the spoken word. In 2018, he released Khichdi (Kitchari), his first major monograph that comprises a ten-year documentation of the changing face of India, to much acclaim. One of photography’s most exciting new voices, he has since undertaken commissions for Another Man, Dazed, Louis Vuitton and more.

Here, Gupta and Sethi discuss navigating the complexities of coming of age in adopted cultures, the role photography can play in examining social structures and communities, and the restorative power of returning to the motherland.

Sunil Gupta: I came to Canada as a teenager. It was a fantasy to step off the plane into this very pristine world. The only thing was my being Indian was completely useless baggage; no one was interested in it. There were hardly any other Indians in downtown Montreal; the few here were all in the suburbs. There were none in my high school. I didn’t have anybody and I realised that everything I knew was completely irrelevant in this place. It wasn’t until I found my sexual activity, which I had been practising for several years in India, happened here and it had a name. By the time I was 17, I discovered a new identity being gay. I joined a gay student society involved in activism and became the photographer for the newsletter we produced. I even had an audience and it was fun. But India – nobody wanted to know or had any interest in it back then except maybe some hippies, but that was about it.

Nick Sethi: Look how much it has changed now: the amount that people in New York and London are trying to incorporate spirituality and yoga into their lives and going back to the roots and Indian culture. I’ve recently begun to relate to my photography as a spiritual practice. I’ve seen you say photography is a healing process. That resonated with me. I was born in the US but I grew up with my parents and grandparents who were all born in India so those kinds of sentiments of Indianness have always been present in my life. My grandparents would tell me: “Do this, it will heal you.”

“I’ve recently begun to relate to my photography as a spiritual practice. I’ve seen you say photography is a healing process. That resonated with me” – Nick Sethi

SG: It sounds like you had extended family around you. I didn’t. I just had my parents. It wasn’t easy to find people of Indian origin and then to find gay ones was next to impossible. I was primarily driven by a gay politics. I was anti-family when I was 20; all the problems – psychological, political – the Indian thing made it worse emphasis on marriage, property, having a son to pass on property. It was capitalism writ large and Gay Liberation was saying: “Forget that, that’s what we need to overthrow: the patriarchy.” I got anti all that but it didn’t make me popular with other Indians at the time [laughs]. I didn’t go back to India until after I came to London. It was 1980. I was 24 and a full-time photo student. People I knew from childhood put me in touch with activists who were doing radical social work in the countryside. I spent six months in a village where I looked at the issues: Why are they so poor? How is it embedded in the structure of the place?

NS: It’s what the world is doing with racism now, not looking at it on a one-to-one level but looking at it on a systematic level.

SG: I was trying to educate myself. My life in India until I left was quite privileged. I was English-speaking, middle class, went to a private school. I was very protected. I went to find out what had been hidden from me. Here was a feudal social structure in action: the village I was in had 37 caste divisions. They were very extreme. You couldn’t cross the boundaries.

NS: It’s almost like a metaphor for the world at large.

SG: When I got off the plane in London and saw all this extreme wealth, and thought, “This can’t be unconnected. How come these guys are so rich and they are so poor? It’s not natural. Something is wrong here.” After graduating, I got involved in cultural politics and began to question documentary photography: Who’s taking the picture? Who’s buying the picture? Who are the publishers? Who owns the media? Do you want to feed this machine? I didn’t want to do that. I stepped away from doing photojournalism because I couldn’t tell the story I wanted to tell. I became more interested what’s happening in photography in South Asia and India, and began to go back and forth to shoot projects, a bit like what you’re doing from New York. It’s easier to travel now. In the 80s and 90s it was a real drama going to India.

NS: In my experience it was, “In two days ... In two days.” Everything moves very slowly. When I arrive in India, I’m never prepared for it. It’s overload, overstimulating – more is more. The work that I make starts with questions that I have about myself or things that I want to explore. When I get to India, it’s like a going back home even though I wasn’t born there.

SG: Do you have much of the language?

NS: I never spoke Hindi growing up but I’ve heard it my whole life. On the street, you can use the act of photographing as a form of communication. I’ve worked with this family that lives on the street in Delhi for over ten years. We can barely communicate because their dialect is so far from the Hindi that I can understand. But we’ve made tens of thousands of pictures together and I consider them close to me. I go back, give them prints, and we make photo albums. It’s very much a family relationship. That process of being outside, working on the street, picking out moments or things you identify with, and taking them back and sitting with them – your work has elements of that, whether it’s the openness of New York or the shyness of India. I see this figuring out who you are as a person through the experience of others.

“I photograph what’s around me, what’s happening to me, and this central question of, ‘What does it mean to be a gay man of Indian origin?’ That’s what stuck with me most of my life and it’s never really gone away” – Sunil Gupta

SG: I photograph what’s around me, what’s happening to me, and this central question of, “What does it mean to be a gay man of Indian origin?” That’s what stuck with me most of my life and it’s never really gone away.

NS: Has that become any clearer to you or has it become more complicated?

SG: It’s shifted over time and place. I went back to live in India in 2005 for about seven years. India seems to have missed Gay Liberation. Suddenly in the mid-00s, people became queer. In the 00s, they got mobile phones and Grindr. Things have changed dramatically. My generation thought this would never happen. All people in my age group are married with very few exceptions.

NS: A few years ago I was doing work with the Kinnar, the third-gender community, a group of people that are written about in ancient scriptures. They’ve always existed in India but I saw they’ve been forced into begging and sex work. It’s sad because a lot of the clients have to be secret about their sexuality. With the change in technology, it opens you up to people you can identify and connect with. How do you feel as someone who didn’t grow up with Grindr?

SG: I find it a little unnatural in the sense that it’s very menu driven and it’s so endless. The most common response I’ve heard from my younger friends is they are very lonely in a way I never was because I’d just go to my local gay bar. I miss cruising. Maybe it’s my age, the analogue world: you go out, see somebody, feel something, and respond to that. You have this spark. But on the internet there’s no spark.

NS: I like that you are relating to it in photography terms. Analogue means there’s room for experimentation.

SG: Not knowing everything. Not knowing the outcomes, taking a risk.

NS: Even just showing up in a city, wandering around, and seeing what will happen. In Delhi, if I go to Chandni Chowk for the 150th time or Sadar Bazaar, I’m always going to get lost.

“I miss cruising. Maybe it’s my age, the analogue world: you go out, see somebody, feel something, and respond to that. You have this spark. But on the internet there’s no spark” – Sunil Gupta

SG: You can have sex just walking in the crowd, or at least used to be able to. It’s so crowded nobody can see what’s happening underneath.

NS: Have you actually done that?

SG: Yeah, that’s how I grew up when I was a teenager. I just had sex everywhere all the time. That was the one disappointing aspect of moving to Canada where nobody seems to do that kind of thing.

NS: I never thought of that as a possibility.

SG: Really? You haven’t had sex? You haven’t met anybody there?

NS: No. Maybe things have changed.

From Here to Eternity. Sunil Gupta. A Retrospective is at The Photographers’ Gallery October 9, 2020 – January 24, 2021. Lovers: Ten Years On is published by Stanley/Barker.

Sunil Gupta will be in conversation with Reiss Smith on September 25, 2020, on the Claire de Rouen and Stanley/Barker Instagram accounts.