Like all great comings-of-age, Deanna Templeton’s What She Said ends with the credits, and the rest of her life. In the final pages of her new photography book with MACK, she meets a boy, Ed.

January 20th 1988

Red Hot Chili Peppers at the Palomino

Well Ann picked me up at 9am, when we got there the lines were really long. We never got into see them. There was a small riot, they played 1/2 a song. Jason and his friend Ed, were so funny. I have a growing crush on Ed, he has pretty eyes.

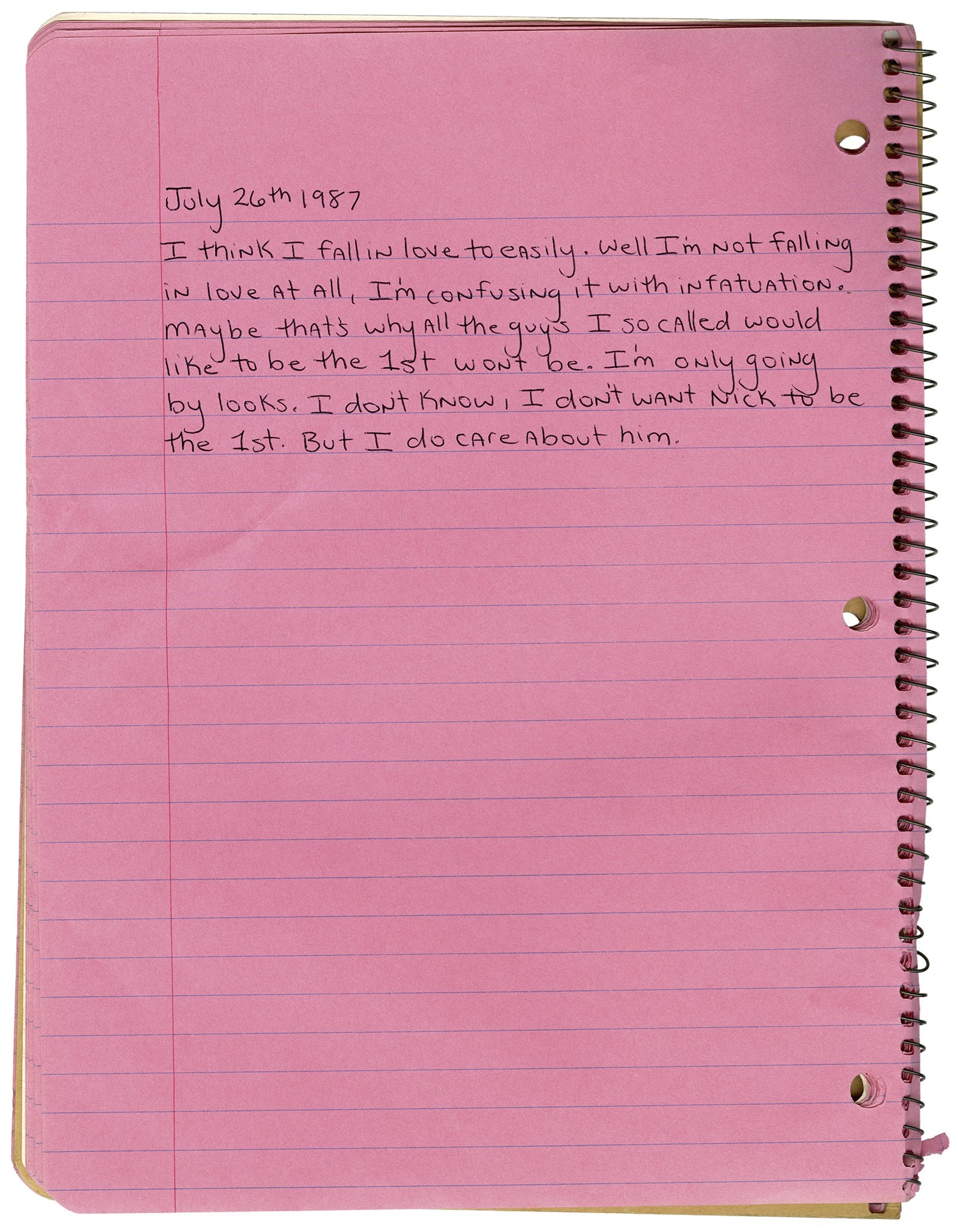

Later, he’ll become her husband, also a photographer, and professional skateboarder. The book itself combines a series of Templeton's actual diary entries and saved concert flyers spanning her own teenage years in the 80s, alongside photographs of various girls she has shot on the street over the past 20 years. But as much as these original, pink-papered journal entries detail failed nights out, fleeting romances, dodgy encounters and familial fights that bring to mind the American films of the decade they were written in, it’s also a uniquely close-up portrait of the photographer as an individual; a teenage girl who thinks she’s not loved by anyone, when clearly she is.

For Templeton, the experience of publishing this book does feel a little like having your padlocked teenage diary discovered by prying eyes. “I don’t mean to sound guarded but it feels a little weird knowing other eyes have seen it and read it,” she says over Skype from her LA home (the book’s entire layout is pinned on a board behind her, because she doesn’t quite feel ready to take it down). “I know it’s the whole point! I’m excited, but as I say, it’s scary. Every time I talk to someone I get nervous, like OK, breathe, breathe ... it’s OK!”

From the 1990s right up until the present day and its Covid restrictions, Templeton has shot photographs of the youth cultures gathering on the street around her local haunts – in the parks, public spaces and punk shows of Huntington Beach, where she lives – as well as abroad in Europe, Australia and Russia. But it’s only fairly recently that she thought of her portraits of girls as their own body of work, and one that could speak with the evidence of her own girlhood in a fruitful way. “I started noticing that a lot of the photographs reminded me either of myself when I was their age, or how I wish I could have been,” she says, admitting that she’s very slow at taking pictures. “It takes a lot for me to press the shutter. I really need to connect somehow. Especially when I’m taking portraits of young women, I run up to them, I get really excited. I didn’t realise till years later that [they] remind me of myself, but with more confidence and more attitude.”

When I ask whether she was taking any photos at the age she wrote the diaries, Templeton admits that her journey to connecting with a camera took a longer and more perilous route than that. “I ran away from home for one night. It was basically just to support a girlfriend who was running away from her really terrible situation with her family, so she wouldn’t be alone. It was a horrible night – I came back. To my parents, I had just run away. My mum bought me a camera, almost [as] a coming home present: like, ‘don’t leave again!’ Things were never talked about, just these different ways of reacting. So I did receive a camera, a camera that was just too much responsibility for a 15-year-old, like a Canon T90. As you can read, I was waaay all over the place.”

“I started noticing that a lot of the photographs reminded me either of myself when I was their age, or how I wish I could have been” – Deanna Templeton

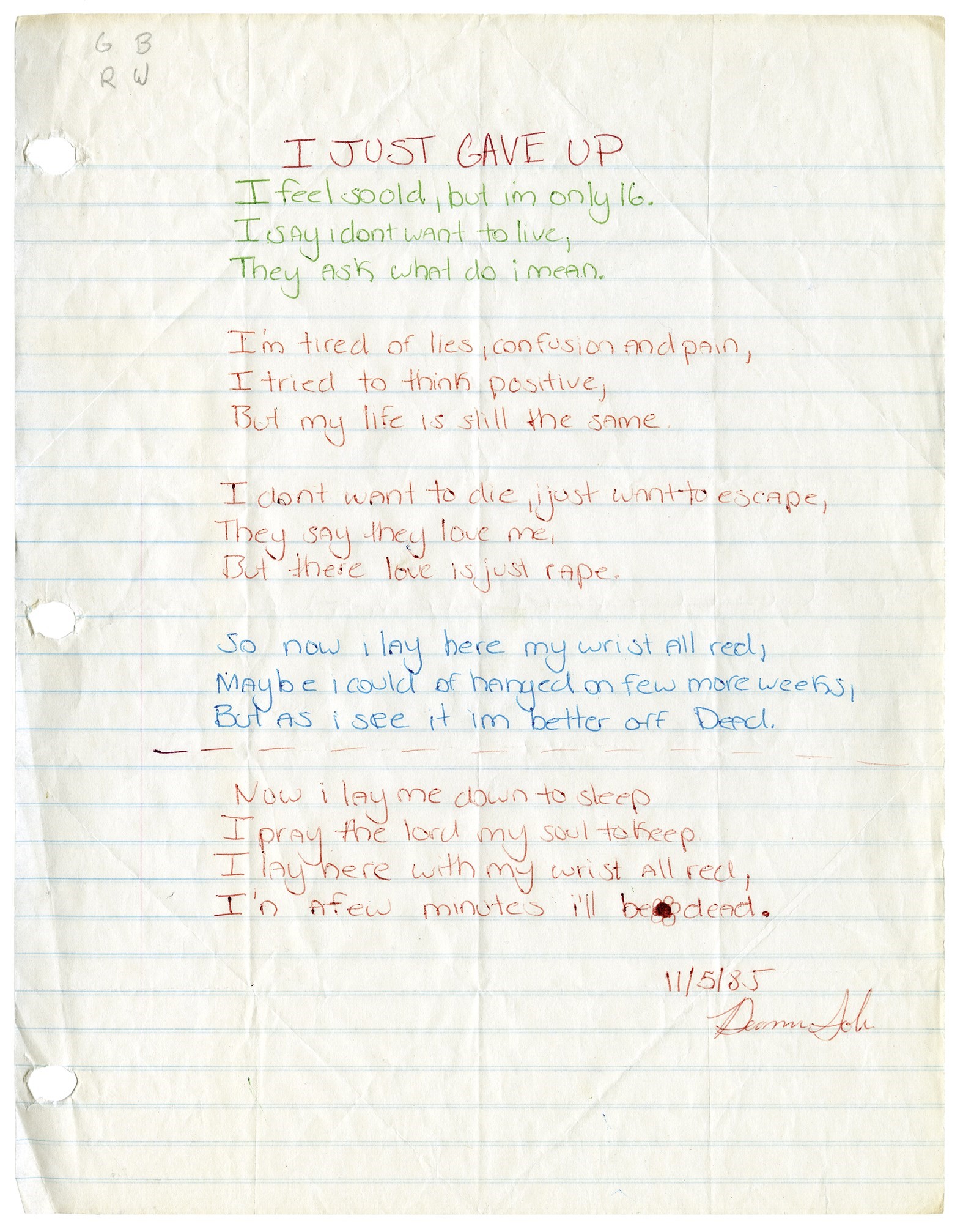

Among the most personal insights of the journal entries are the references to Templeton’s struggle with body-image issues, resulting in periods in which she would starve herself. That these sections are not easy ones to read is testament to the photographer’s genuine intention with her book, and desire to help girls who may come across it. “It is something that just keeps going,” she says sadly of eating disorders among girls. “There’s one girl I follow, who is not in my book. I think she might be a survivor from anorexia, she posts resources from other women. [It means a lot] to see that platform that exists now for boys or girls who have suffered from eating disorders, or [with the #MeToo movement], sexual abuse. That strength and solidarity. Of course, you’re going to see women exploited also on social media – but you have the other side too.”

“If you hang in there long enough you will hopefully get through this,” she continues, with emotion, of the message she wants What She Said to convey. “For me, even the thought of wanting to die [in one diary entry, she writes a suicide note, with funeral instructions]. It breaks my heart to think of people who actually do go through with it and don’t see any other alternative. It breaks my heart to think of people who don’t even have just one person. For me I just needed one person to show they really cared. I just want people to know there’s a light at the end of the tunnel if you just hang on. Re-reading my stuff, what I wish I could have said to myself and what I would want to say to other people is just, give yourself a break, don’t be so hard on yourself. The point of this book was that, basically. Me giving myself a break, finally [laughs].”

“What I would want to say to other people is just, give yourself a break, don’t be so hard on yourself. The point of this book was that, basically. Me giving myself a break, finally” – Deanna Templeton

You’ll immediately recognise many of the girls in the book, who felt, for me, like close relatives of all the girls I used to know, including myself. Girls who write all over themselves in marker pens when they’re bored. Girls who wear hardcore band tees that say “TEEN CUNT” and “SUICIDAL TENDENCIES”, but who are probably really softly-spoken. One girl in a hooded cloak reminded me of my best friend in school wearing one, and pulling it off so well that nobody knew what to say exactly. But something I only noticed on the second or third flick through of the book is that the book opens on a black-and-white self-portrait of Deanna, snotty and crying, and ends with some colour photographs of her taken by others, likely family members and friends. If this were a coming-of-age film, the monochrome to colour transition could mean something, but mainly I think about the way the closing shots show teenage Deanna out in the world, doing things, in the eyes of those who really did love her for who she was – and admired her strength in a way she just couldn’t yet.

Mainly, Templeton seems to take pride in the girls she’s met and taken photographs of – as personal as this project is, it’s also really a celebration of all those strong young women. “In my teenage years I would never have thought about wearing a t-shirt that said ‘TEEN CUNT’ on it. I just love it. I wish I could have got a portrait of that girl without her glasses on, and maybe thrown her on the cover instead of me.”

What She Said by Deanna Templeton is published by MACK.