Next month, Rizzoli publish Making It Up As We Go Along – a must-have visual archive celebrating the 20-year visual history of Dazed & Confused magazine, edited by Jefferson Hack and Jo-Ann Furniss. Here, Mark Sanders, original art editor of Dazed

Next month, Rizzoli publish Making It Up As We Go Along – a must-have visual archive celebrating the 20-year visual history of Dazed & Confused magazine, edited by Jefferson Hack and Jo-Ann Furniss. Unsurprisingly, it’s a veritable smorgasbord of stimuli featuring iconic, game-changing work from some of the world’s greatest photographers, stylists and artists. John-Paul Pryor is one of the additional editors who worked on the forthcoming publication, sourcing interviews with some of the in-house movers and shakers that defined the early years of the magazine, and some of those contributors whose specially commissioned works helped to push the form forward in unique and boundary-defying ways. The person responsible for the groundbreaking art commissions that in no small part came to define the magazine was the original arts editor Mark Sanders, who reframed the contemporary art interview with special projects that would witness The Chapman Brothers re-sit their GCSEs, the wanton construction of an entirely mythical self-mutilating artist named Bruce Louden (who would garner attention from the world press), the journalistic results of week-long drinking binges with Damien Hirst and Angus Fairhurst, an exhibiiton of Astrid Proll's photos of the Baader Meinhoff Complex at the now decommissioned Dazed Gallery, and much more besides. Sanders was looking at some of these now renowned artists before anyone else, and he intuitively leaned towards the more Dionysian members of the YBA movement. Here, the curator and co-director of All Visual Arts discusses with Pryor the early days of the magazine.

When did you first become aware of Dazed & Confused?

The first one I ever saw was issue five – Death Of A Cover Star – with the silver cover. I was making a living fly-postering at the time. (Laughs) I mean, I had done a MA in Art History at UCL - I knew I was pretty much unemployable! Jefferson and Rankin had just set up the club High And Dry in Leicester Square, and I actually first met them to fly-poster for their club.

What was the mission plan right at the beginning?

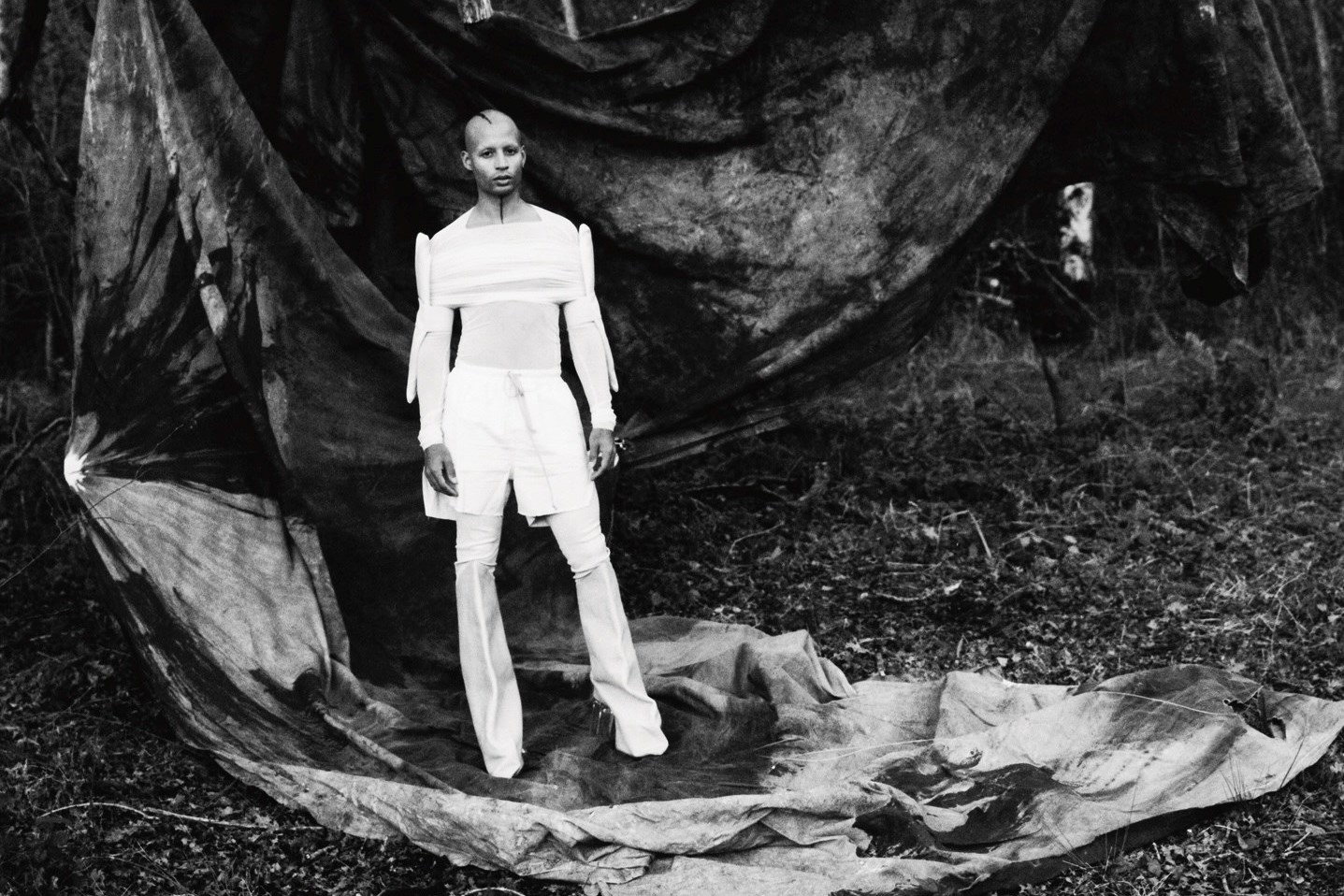

The big word being bandied around between Jefferson and I in the beginning was ‘collaboration’. One thing that we didn’t do – and that we sometimes received criticism for – is we never set ourselves up as judge and jury. Our art editorial stopped with us deciding who we wanted to work with, and when we did work with them it was about bringing them into the family and giving them complete open access. We wanted the magazine to be proactive, as opposed to being a passive observer of culture.

British culture was exploding at that time, wasn’t it?

The lucky thing that we had going for the magazine was that everything was in London. It would have been very difficult to get the magazine off the ground anywhere else. It was all on our doorstep and that made life easy editorially, for a magazine that didn't have any money.

There is a sense of breaking down the way in which art had been reported upon before – a lot of the interviews you did were quite irreverent at times. The relationship with The Chapmans seems particularly significant…

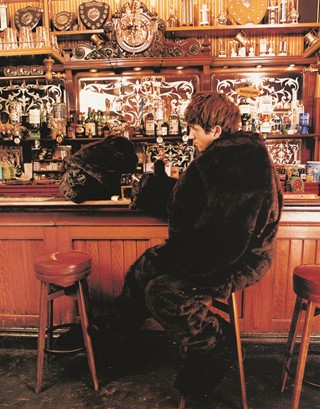

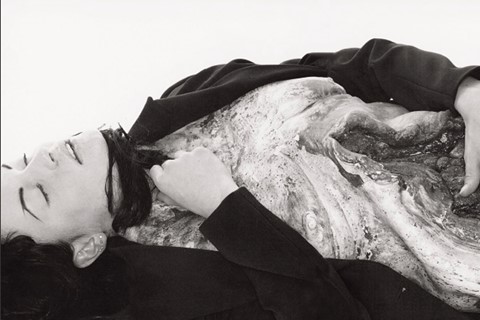

I think I gave The Chapmans one of their first pieces of press. What we decided to do was say, 'Let's get involved and let's include the artists in our playpen'. So, we would bring The Chapmans in and say, ‘Here, take eight pages, and do what you want.' Of course, there were interviews with them in Frieze, but it was very much 'art speak'. What we wanted was make contemporary art accessible. We were people trying to be creative on our own terms, and we gravitated towards artists that were doing the same thing. I am immensely proud that we featured Paul McCarthy in Dazed & Confused in 1996. He is now a huge artist all over the world. When we met him, he was just being rediscovered – because he had been an artist since the late 60s. We were very early on with that, extremely early.

There seemed to be a situationist aesthetic at work in the collaborations – a sense of playing with culture…

It was similar in that it was a way of loosening things up. All those Situationist guys used to write about how they would take a map of Paris and walk around Amsterdam with it, because that opens you up to new ideas. These interview techniques were exactly like that. It was a big statement for us. We were saying: "The magazine is not just ours, it’s yours as well." I love Barbara Kruger’s piece, where she took images from Dazed and then put her text over the top. It was just perfect. Then there’s Jake and Dinos re-sitting their GCSE exams… These kinds of art projects were very important because that’s what turned the magazine into a platform for experimentation. Making up an artist called Bruce Louden is a perfect example of that. We figured if a magazine has the power to give promotion or make people famous, then why can’t we just make-up someone to be famous – it doesn't matter if he doesn't exist. That article sold all over the world. We had to stop when someone phoned me from a British newspaper and asked whether he was real. I said, 'No comment!'

There was definitely a sense of the magazine being in cahoots with the artists…

It’s the difference between being a paid journalist and having the pleasure of not being one. Dazed originally started as a fanzine, and the wonderful was that it was one of the best calling cards you can ever imagine. You could wake up in your bed-sit in Ladbroke Grove and think to yourself: "Who do I want speak to today?" It gave us this incredible access.

What do you think was the catalyst for it?

We were living in the last years of a Tory government. People forget that, but for our generation it was a big deal. Things were changing and popular culture was almost fragmenting around us. We were trying to understand that and we took it back to just doing it ourselves. We realised that culture wasn’t this ‘thing’ that we have to accept and consume, which is effectively what happens with TV and most magazines now. Culture is something that’s made by people, and you can make it yourself. That’s what we tried to do with Dazed & Confused.