“They capture the full arc of my experience of HIV and Aids,” says New York-based artist Eric Rhein of the photographs published in his new book, Lifelines

There is an invisible subject in Eric Rhein’s recently-published book, Lifelines, which dedicated to the photographs the artist made between 1989 and 2012, and that is late uncle, the LGBTQ activist, Lige Clarke. When Rhein visited him and his partner, Jack, in New York as a child, little did he know that he’d later also call East Village home, as a student at School of Visual Arts. “While my uncle was murdered in 1975, when I was 14, his influence continued through my discovery of books that he wrote with his partner,” Rhein tells AnOther. He found these books in his mother’s cedar chest at home in Kentucky, which “provided me with an early education and expansive insight into what it might be like live as a liberated gay man”.

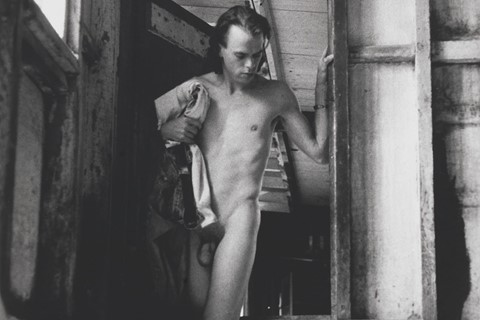

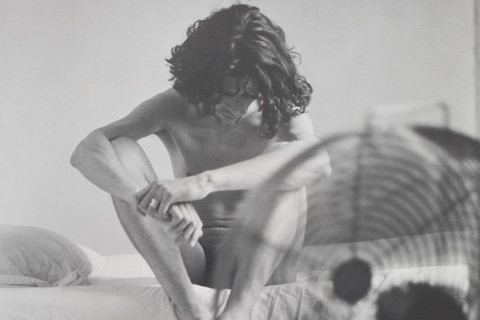

Published by Institute 193, Lifelines is both a catalogue and a visual memoir that chronicles the lives of friends, comrades, lovers, and peers according to Rhein, who today balances bent-wire and collaged sculptures with black and white photographs shot with a 35mm film and “illuminated within sun-drenched interiors”. Elated and desiring, these images depict young men wrapped in bedsheets, as well as in each others’ arms – which feels somewhat remote from the realities of the gay life in the US during the late 20th century. “They capture the full arc of my experience of HIV and Aids – from the time I was first diagnosed – to a ‘return to life’ via the 1996 availability of the protease inhibitors,” explains the artist.

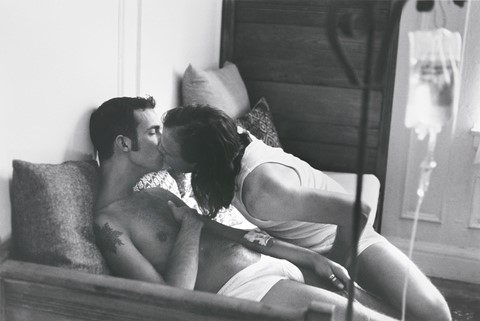

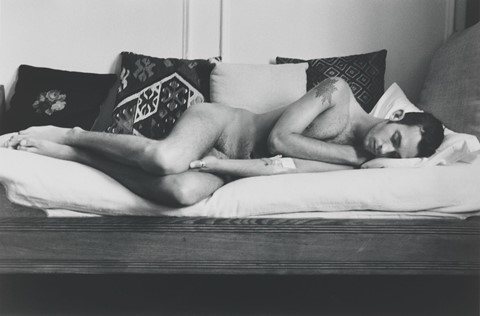

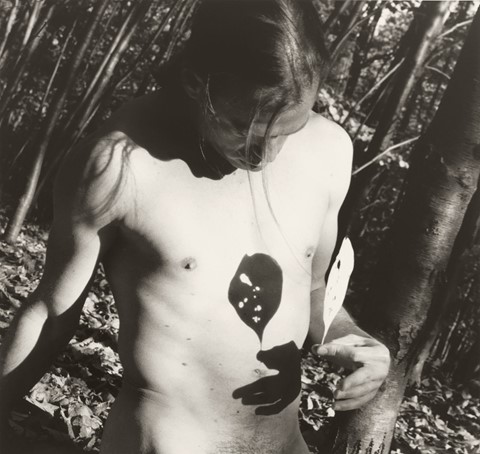

Lush nature or serene interiors provide the backdrop for the nudes’ mellow gestures, reminiscent of those from the classical European painting. In Wave and Daydreaming (both 1991), a joyful man plays with his mischievous dog who seems as conscious about the camera as the human. William – Silhouette (1992) pairs a man’s body with his spectral reflection over a beach throw in Martha’s Vineyard, with the textural sand contrasting the sky’s absorbing endlessness. Veil 1 and Veil 2 (both 1994) capture a theatrical moment, Rhein and another man encapsulated by a mosquito net draped over their bed like a haunting ghost. The artist considers his relationship with his lens an “instinctual aesthetic response to my subject,” and says, “these images come out of the lived experiences of myself and my relationships.” They are the crops of idyllic days spent between heartbreak and tenderness, as well as contemplation and bliss.

Amid the pictures’ vivacity rest traces of living with HIV and Aids. The monograph’s seminal picture, Lifeline (Self portrait with Ken Davis), 1996 shows Rhein helping his lover with an injection, while a tube snakes from his arm through an IV bag. Rather than a hospital bed, they lounge over a wooden ottoman rich with patterned pillows. Their clinical act is defied by a biblical juxtaposition, serenely composed yet alarming with its intense reality. Rhein took his first auto-portrait in 1992, unaware of starting “a multi-decade project to document my (and my friends and lovers’) personal arcs through the Aids crisis.” After surviving a plague with a camera in his hand, the artist considers the book format a “wholeness” of moments that have thus far slipped through a crisis.