As her first retrospective book and exhibition launch, Brazilian photographer Mona Kuhn tells Miss Rosen about her distinctive approach to the nude

As a young girl coming of age in 1980s Brazil, Mona Kuhn discovered the power of photography when she received a Kodak Pocket Instamatic camera for her 12th birthday. “Photography is a modern, fast-paced medium and in a way that is what I like because I have a very restless side to me – but at the same time it scares me,” Kuhn tells AnOther in advance of the April 6 publication of Mona Kuhn: Works (Thames & Hudson), her first retrospective monograph chronicling a quarter century of work, selections from which are now on view at Edwynn Houk Gallery in New York and opening online March 11 at Flowers Gallery in London.

Since she was a teenager, Kuhn had been drawn to figurative work, particularly that of painters including Gustav Klimt, Oskar Kokoschka, and Egon Schiele. After meeting Braziian artist Mário Cravo Neto, who used figurative photography to investigate the Afro Brazilian heritage and mysticism in Bahia, Kuhn embarked on her first study of the human form.

“I always wanted to go against how fast-paced the medium is, and work with nudes as a way of stopping time,” Kuhn reveals. “I was interested in the nude because it wasn’t limited by fashion; it was open-ended. It was not an easy thing because nudes have been done a lot, maybe in ways I do not think are best. At the time I was in college, in the early 90s, Helmut Newton and Herb Ritts were iconic, but it was not how I wanted it to be.”

Rather than follow the prevailing trend, Kuhn carved her own path, moving to San Francisco in 1993 at the height of the Bay Area Figurative Movement. Drawn to the idea of naturism, seeing the body in harmony with nature rather than an object of “show and tell”, Kuhn strove to create nudes that pushed past the documentary side of photography and entered into a more imaginative realm.

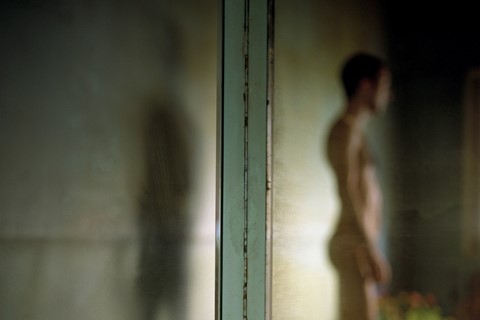

“I had to go away from the sharp representation that was happening in order to be a lot more emotional and inquisitive,” Kuhn says. “I wanted to bring the vocabulary of arts and continue the discourse of the figurative in photography. In a painting, it’s not as blunt. You can smear, hide, and reveal things, so I did that with the focus. My point is to show a connection, a moment in time. Maybe the selective focus can question if this moment really existed or not.”

For Kuhn, the connection is forged long before the photograph is made, as her subjects are friends and collaborators she has known for years, even decades. “We talk about the world, our families, relationships, college, whatever it is – we talk about everything. Eventually they look at me, and I look at them. Then there is a pause and they ask, ‘So what are you working on lately?’” Kuhn says with a laugh.

From their encounter, seeds are planted and ideas begin to take shape within the fertile recesses of the artist’s unconscious mind. Never one to rush, Kuhn enjoys the process of thinking, considering, and allowing things to ripen before she moves forward. “I don’t just go and click. I could photograph 300 people in one day, but none of those would have any meaning besides just being naked,” Kuhn says.

“When I’m working I like to be by myself and alone,” she continues. “I’m married and I have a son but when I am photographing I like the solitude for myself. I have space to reconnect myself with my inner voice. I close my eyes and let that conversation with the friend sink a little bit and think about how we can transfer into a moment in photography. Sometimes those metaphors come slowly; they bloom over time.”

These metaphors weave into an exquisite tapestry, one whose threads can be traced throughout Mona Kuhn: Works, which includes works from the series Evidence, Native, Venezia, Bordeaux Series, Private, Bushes and Succulents, and She Disappeared into Complete Silence, which she describes as her most fulfilling work to date.

Made between 2014-2019 with family friend Jacintha in a glass house on the edge of Joshua Tree National Park, She Disappeared into Complete Silence takes its name from Louise Bourgeois’ first monograph as it explores the female nude liberated by the ethereal glory of the “Golden Hour” of the desert.

“My best work starts when they forget they are naked. We entered a parallel reality, something that is lifted from the everyday, a quiet moment that is floating there. It takes time to escape your thoughts,” Kuhn says.

“We spent the whole day hanging out talking, reading, listening to music that would allow your thoughts to wander in space. At times I would say, ‘What you are doing is beautiful. Just stay there and I will bring the camera.’ I would be observing what we were doing and allow things to happen naturally.”

Mona Kuhn: Works is published by Thames & Hudson on 11 March. An exhibition of the same name is on view at Edwynn Houk Gallery in New York through 17 April and online at Flowers Gallery in London.