A sumptuous new book pays tribute to the artist, who became one of Japan’s leading erotic visionaries in the 1960s and 70s

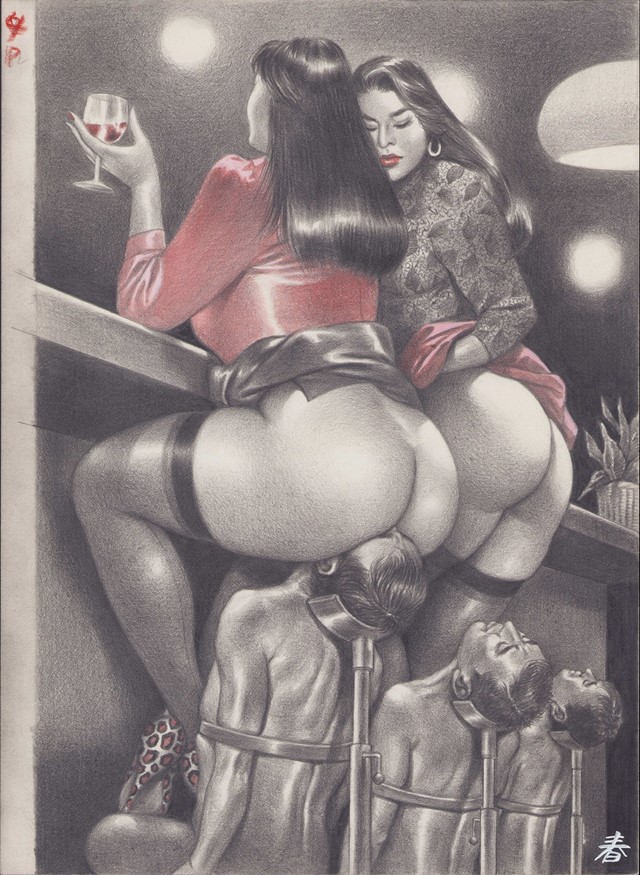

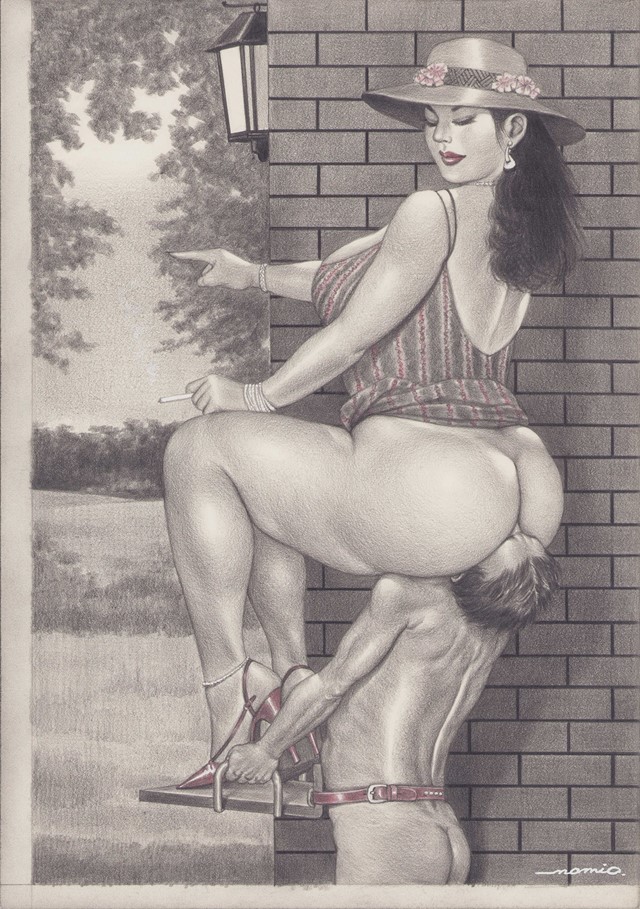

On 24 April 2020, Japanese artist Namio Harukawa died at the age of 72, leaving behind an extraordinary body of work that explored his love of female domination. Obsessed with scenes of erotic asphyxiation, wherein voluptuous women revel in the pleasures of facesitting and transform diminutive men into human furniture, Harukawa established himself as one of Japan’s best known fetish artists in the 1960s and 70s.

Working under a pseudonym formed from an anagram of “Naomi”, the heroine in Tanizaki Jun’ichirō’s novel Chijin no ai / A Fool’s Love, and the surname of film actress Masumi Harukawa, the artist got his start in high school. There, he contributed drawings to Kitan Club, a leading post-war pulp magazine best known for publishing sadomasochistic artwork and prose. But it wasn’t until the 2000s that his work became recognised by everyone, from Japanese avant-garde luminaries Shuji Terayama and Onoroku Dan to Madonna.

“The popularity of Harukawa’s work can be seen in the context of the rise of feminism, fat liberation and the body positivity movement. Although Harukawa’s work can be compared to Robert Crumb, there is no other artist that depicts big girls having fun like that,” says academic, curator and editor Pernilla Ellens, who wrote the introduction to Namio Harukawa (Baron), the sumptuous new book that brings together some of the artist’s most iconic works.

Within the long-standing tradition of Japanese erotica and BDSM, Harukawa’s work stands out, in large part due to his celebration of buttocks. In a world full of ’skinny Minnies,’ Harukawa pays tribute to women of Rubenesque form, depicting them as figures of beauty, desire, glamour and joy. “He really loved the big gals and I think he wanted them to love themselves,” Ellens says. “That’s why his work is so inspirational, as fat women in our fatphobic society who are still marginalised and seen as unattractive, in Harakuwa’s work the subjects take centre stage in all their glory.”

At a time when the Brazilian butt lift has become the fastest-growing cosmetic procedure in the world, the female posterior has been restored to its rightful place of veneration. But bootie worship is nothing new: for as long as people have made art, they have thrown ass – in dance, music, drawings, paintings, and sculpture dating back to the Venus of Willendorf (24,000-22,000 BC) and Venus Lespugue (25,000 BC).

“The buttocks represent the primitive image of femininity, sexuality, fertility and lust,” Ellens says. “In the 21st century, we saw a rise of the butt as the focal point in today’s cultural imagery, through song lyrics, music videos, photography, magazine covers, articles, TV, pornography, social networks, fitness culture and plastic surgery. The popularity of the butt has to do with the power of the image. The digital revolution, and especially the launch of Instagram in 2010, enlarged the power and influence of these images as they’re now distributed worldwide.”

With the idealisation of the ample rump, it is no surprise the internet rediscovered and embraced Harukawa’s work, sharing it on popular sites including Tumblr, Reddit, Pinterest and FetLife, the largest online social media site for the fetish and BDSM community. But Harukawa did more than embrace the butt – he transformed it into a symbol of dominance.

“Harukawa was committed to the regime of ’absolute Ganmen Kijo Shugi (facesitting principle)’. He portrays the male subjects as small, insignificant, sometimes faceless and emasculated, and always used for the pleasure of the female subjects. They are being objectified, but not sexualised. This is a complete role reversal in our modern patriarchal society,” Ellens says.

“What we can learn from the work of Harukawa, is that it’s more than OK to be a sub between the sheets if you are a man. The man who trusts his partner enough to submit his entire being to her will, bonds on a level that goes beyond the bedroom. Female domination is more than sexual. It is also social, emotional and spiritual. Art can help liberate one from stifling standards, because it opens up the conversation and gets people thinking about their desires.”

Namio Harukawa, published by Baron, is out now.