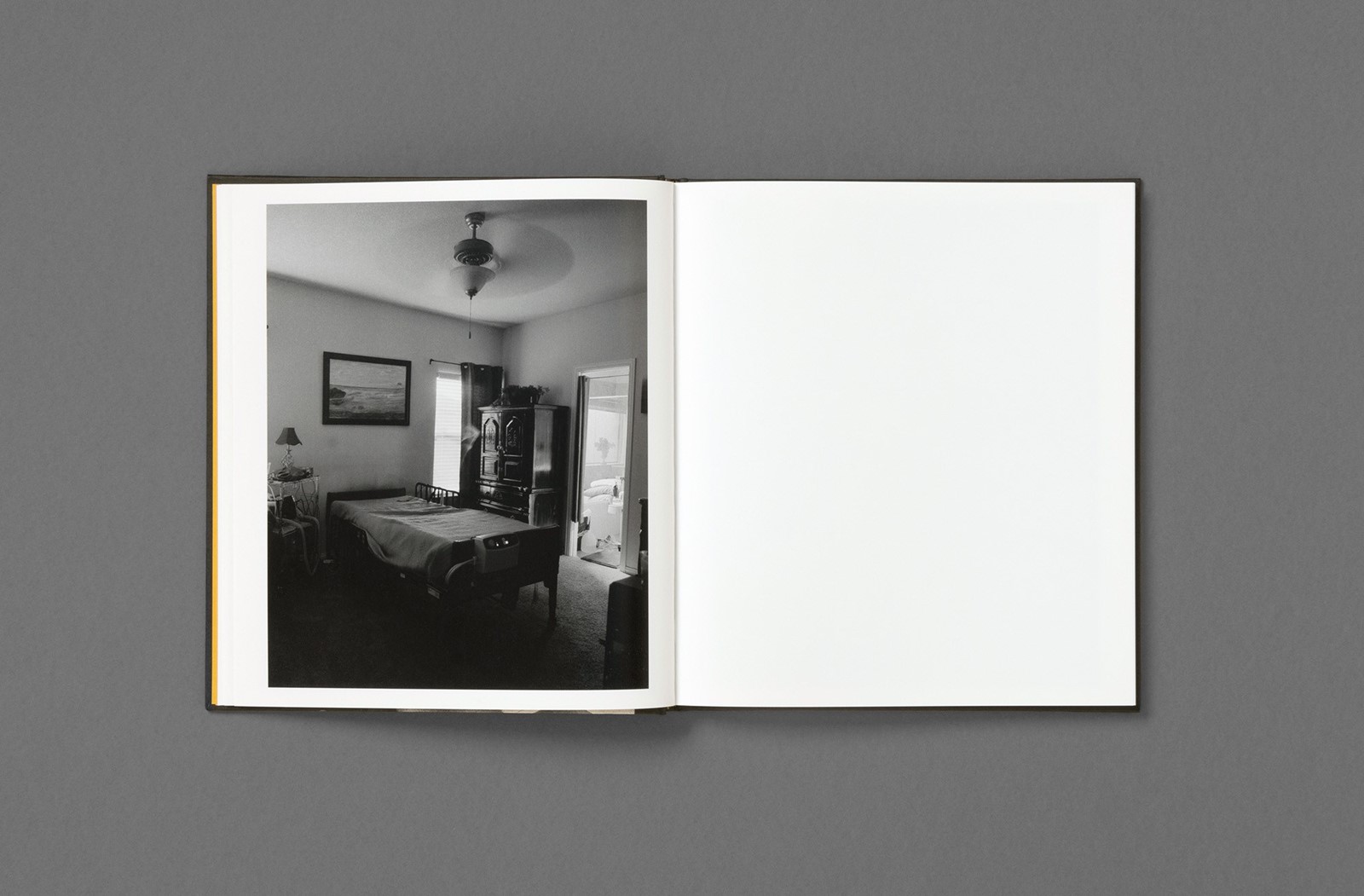

There’s a photograph of a wheat field in Rahim Fortune’s new book, I can't stand to see you cry; the pale stalks bend in the deep night sky, the crop flooded by the harsh light of Fortune’s camera flash. The photo was taken last year in Austin, Texas, on the night Fortune’s father was first hospitalised for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). In two months, Fortune would witness his father’s body fail him, watching as he was taken twice more before passing away.

“The first time he was hospitalised, I made the image of the empty bed,” Fortune says, signalling to a photo of his father’s vacant room, the ceiling fan blurry as it whirrs against the Texas humidity. “That night, my sister went with me, and I made this photograph with flash in the wheat field. That image represents so much to me. It’s like the field of the abyss.”

I can't stand to see you cry is Austin-born, New York-based Fortune’s second book, a culmination of the last five years of “Black love, photography, and history”, that he, and his community, have experienced. “It’s a coming-of-age story in Texas,” he explains.

In March last year, Fortune left his apartment and headed to Austin to celebrate his birthday with his family, unaware of the imminent change looming on the horizon. Suddenly, the US plunged into lockdown, and with stay-at-home orders in place, Fortune remained in Texas. His week-long visit turned to months and would ultimately shape the future lives of him and his loved ones.

His father’s health declined parallel to the country’s own, and the pandemic soon claimed thousands of lives every day. America’s sickness manifested in other ways too. In May, the murder of George Floyd lit a match that blazed a trail across the world, mobilising millions to march in the long fight for racial justice – often at the hands of more police violence. Simultaneously, Fortune’s career continued to rise, placing him on ground zero of history as it was made, with assignments for the New York Times and Rolling Stone.

Fortune first came to photography after buying a Pentax SLR 35mm for 99 cents at the thrift store he worked for in his early 20s. His “breakthrough” was meeting Eli Reed, the first Black photographer on Magnum’s books, at the photo lab he later worked. “I was introduced to that legacy,” he recalls. “That really moved me, and that’s when I started understanding what documentary photography was, and I began my first projects.”

Initially, I can't stand to see you cry formed as a documentation of his father’s illness, but Fortune, with the help of publisher Loose Joints, was able “to get at a deeper psychology” of the moment. While one photo stems back to 2016, much of the work was shot in the past year, even as recent as this year. “It’s like a film noir Western of my life,” he adds.

Here, Fortune speaks in depth about making I can't stand to see you cry, how growing up in the South shaped his vision, why he must be present, and how he’s holding onto hope.

AnOther Magazine: How did growing up in the South shape your vision as a photographer?

Rahim Fortune: A lot of what I’m interested in is representing what I grew up seeing. It was even more particular for me since I grew up in Oklahoma and saw a lot of forces. That, married with my family in Texas, which is a very large Black family, and very much southern. [I was inspired by] the style of my grandfather, and the photos I saw of him in Vietnam, and the photographs I saw of my father as a young adult in the 70s. The family archive and then also through photographing my family pretty extensively, photographing my grandma a lot. I learned certain sensibilities through doing that work.

AM: Who are some of the people in the book?

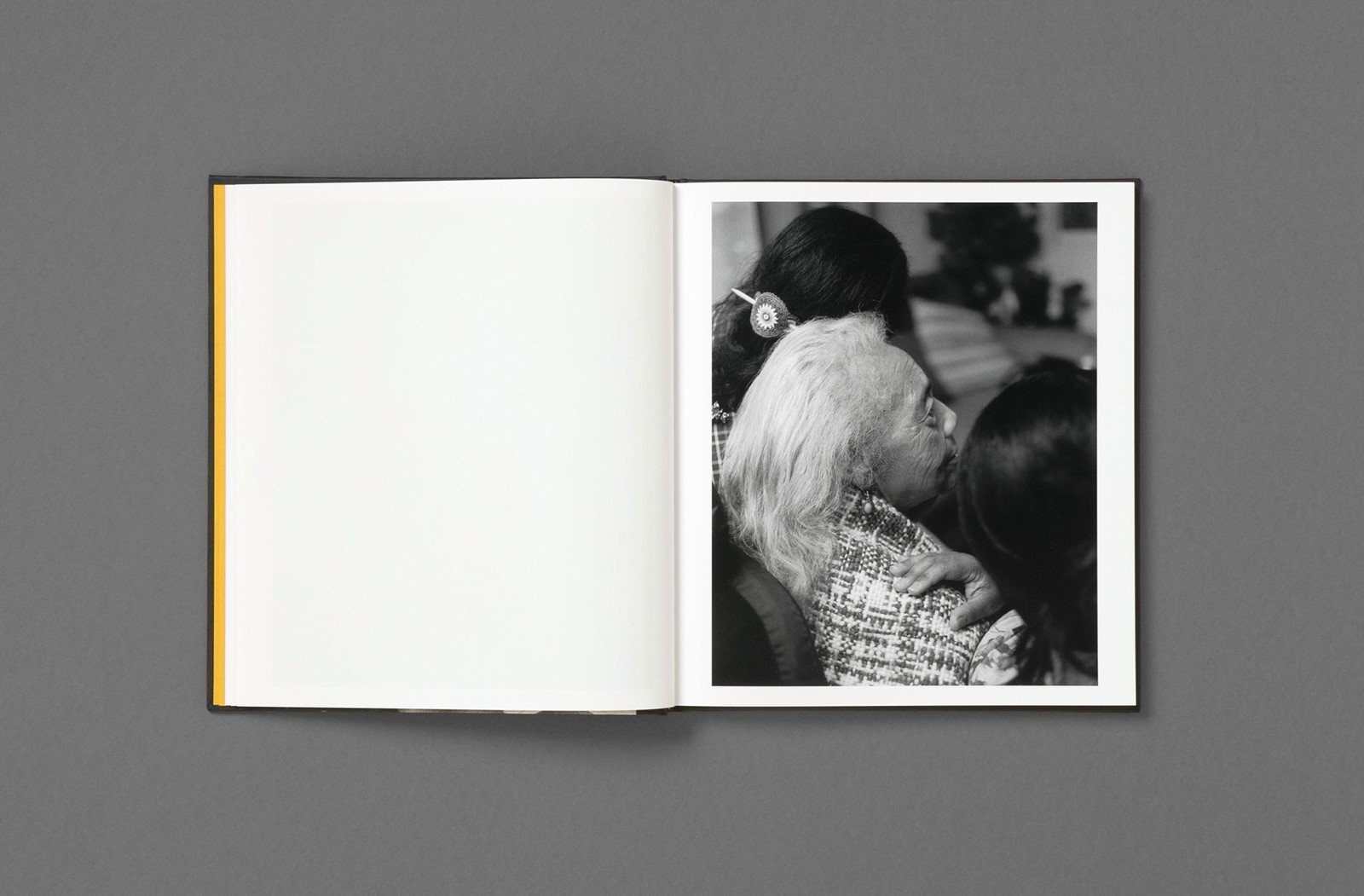

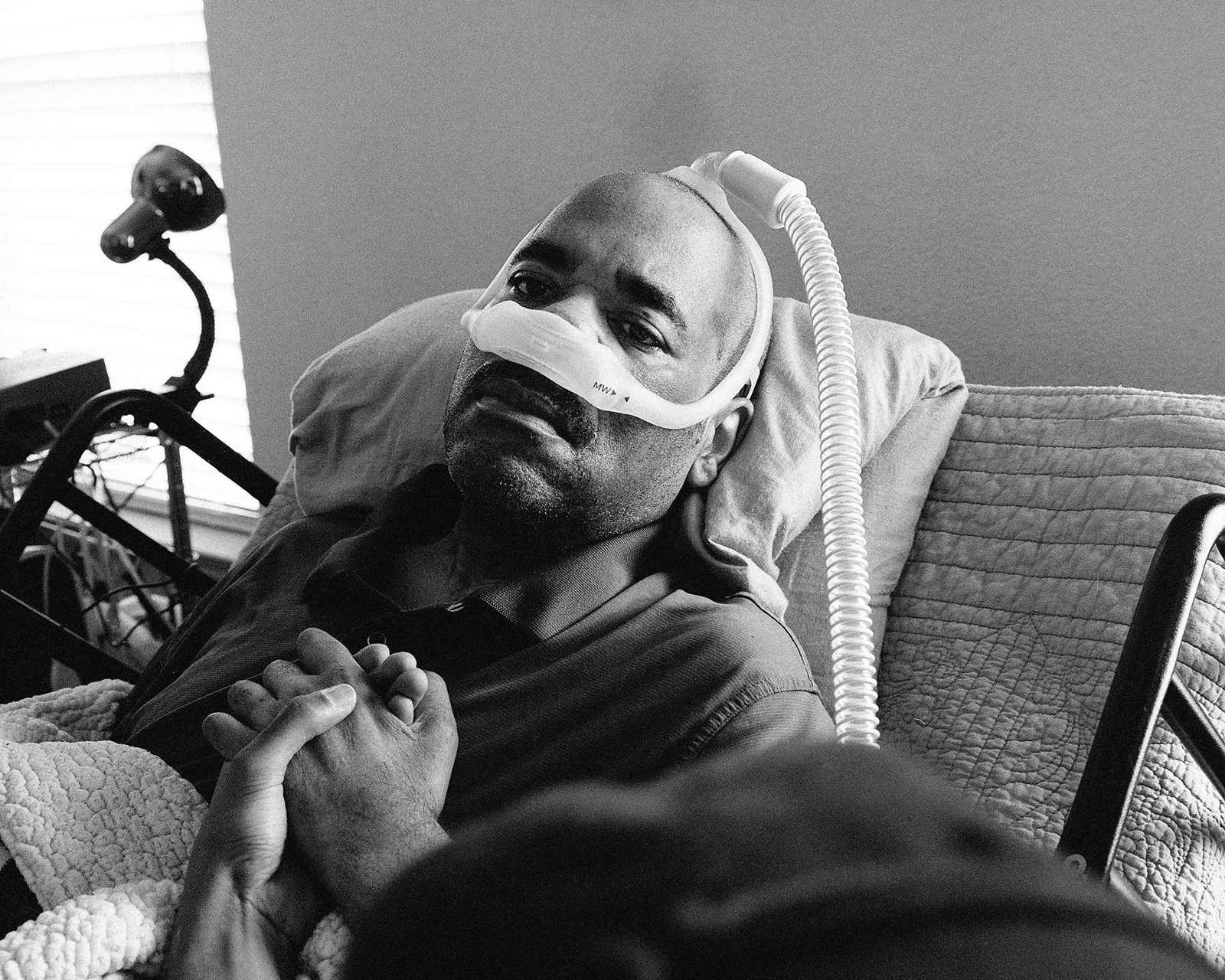

RF: The more prominent ones are mostly my family. There’s a portrait of my father towards the end. There are a few images of my sister, one when she’s tying her hair up, another one in which her arms are crossed. The photograph of [my partner] Miranda and me was made in collaboration with my sister. I set up the camera, and she focused it and pressed the shutter. There’s an image of my grandmother where she’s enclosed by her two daughters, my aunts.

There are a lot of friends in the book, longtime friends or collaborators, and also a networking community of Black artists in Austin. There are street portraits, but I really wasn’t interested in looking deeply into the lives of others. Even though that is there, I hope that the process of it was not too intrusive into others’ lives the way that documentary photography can be. That interested me, using the people who are so close to me, rather than relying on strangers for metaphor.

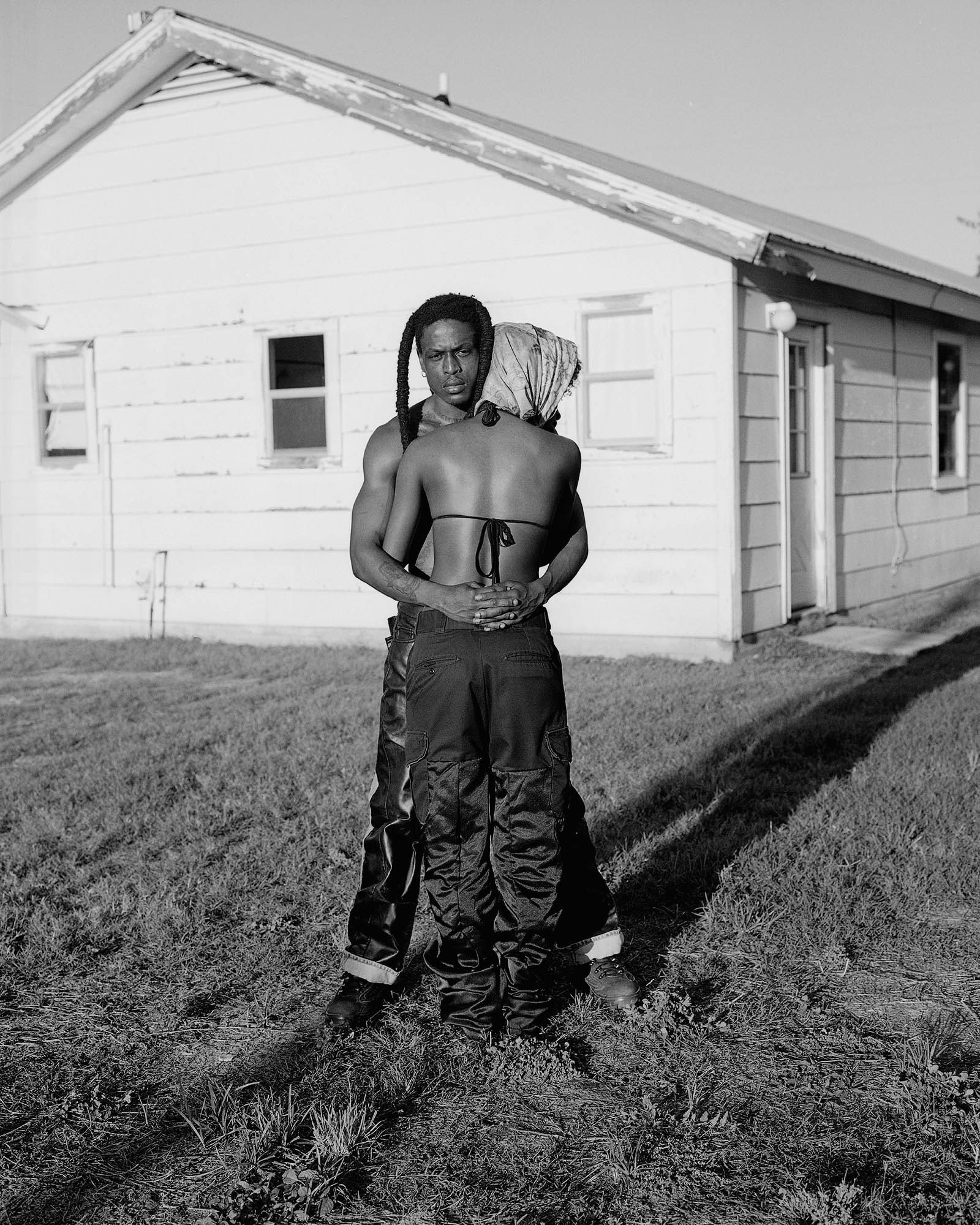

AM: The cover image is you and your partner, fellow photographer Miranda Barnes. Why did you choose that photo to hold the book together?

RF: Our relationship during this pandemic, and our love for each other, really spoke to a larger push for holding on, when you’ve gone through so many things. Thinking about the [book] title and what that represents, that photo of us embracing, which was also made in part with the New York Times ‘At Home’ cover, a very similar image made in the same sequence of days. That photo reminded me of a Roy DeCarava photo, the dark light, and to me, it spoke to the legacy of Black love, photography, and history, and that’s what the book is about, that whole legacy.

“I hope that the process of it was not too intrusive into others’ lives the way that documentary photography can be. That interested me, using the people who are so close to me, rather than relying on strangers for metaphor” – Rahim Fortune

AM: In the press text for the book, you wrote: “Many nights we’d leave his room both knowing his condition was getting much worse, but we chose to say nothing of it.” I feel like you’re talking about your father, but there feels like there’s more to it.

RF: That quote speaks collectively to the condition of our nation and our inability to speak about how much worse our situation has become. I feel like that’s what we’re going through as a society with all of the shootings, the violence, also a pandemic. We could see the condition getting worse, but we do carry on our lives day-to-day, in as much as we’re allowed. That’s the tension we’re all going through right now. It’s not new, but things are extremely amplified.

AM: I keep going back to the photo of fellow photographer Gem Hale, with the tattooed outline of Texas with stitches down its middle. That photo feels significant. How did the national issues compound in Texas?

RF: A man named Mike Ramos was murdered by police (in April 2020). A highly publicised case caught on video that was already happening in Austin when George Floyd was murdered. There was a very significant protest in Austin where they shut down a section of the highway, and that is where Gem was shot (by a rubber bullet). Some of the other photographs were made around that same time, so it definitely plays into the book’s narrative. Thinking about safety and violence, and the space we’re allowed to exist.

AM: The title of the book is I can’t stand to see you cry. I know that’s a song, is that where it comes from?

RF: There are a few I can’t stand to see you cry songs, but the particular song that inspired me to name the book was performed by The Whatnots, a group from Baltimore. That rendition of the song represented an element that the book was about. My father grew up in that generation and was very much raised on funk and soul music. That’s what I grew up hearing and still listened to with my father. There would be moments in his illness where we would just lay down and put on a mix of music, and a lot of those songs really resonated. But that that particular song and that title brings me to multiple moments of really not wanting to see somebody cry, quite literally. My grandmother at my father’s funeral, things like that.

AM: Your father also played music, right?

RF: He played music until he wasn’t able to pick up a guitar. He had quite an extensive collection of guitars, and we were a very musical family. Anytime he would have anybody over, he would be like, “Son, grab a guitar, we’re gonna play music together.” Growing up, it was almost a chore, like, “Alright, pops.” The music is a huge part.

“I think the book is extremely hopeful in the sense that it is about self-love. I really do think it should be viewed in that way. There is hope and overcoming. Resilience is a strong theme I’m really interested in” – Rahim Fortune

AM: In an earlier interview for your book, Oklahoma, you mentioned that you used the camera as a buffer between yourself and the experience of returning to Oklahoma for the first time since your mother passed away. Do you still use your camera as a way to comprehend situations?

RF: It’s something I’ve been battling with because of the weight of some of this work, there is no buffer for it. Just producing this in book form required an extreme amount of work. All of that was really taxing on me. But as far as using [the camera] as a buffer, I would say not so much. I think I’m pretty present. I owe it to all of the subjects that I photograph, not people, but subject matter, and history, and my ancestors, and other people’s ancestors, I owe presence. I have to be present when I’m photographing.

That might have been the case for Oklahoma, but I still very much experienced all of the things. I was very eager to start to make photographs at that time, and I figured that story was worth telling in that way. I hope it moves people who have a similar experience, if they grew up on one of the territories of Oklahoma or if they lost a parent to suicide. I hope it provides them a visibility or affirmation we’re all looking for: to be seen, heard, and represented.

AM: What is it about black and white that calls to you?

RF: Black and white was my first love because of the ability to process it yourself. I formed my voice and tonality through my process, even down to how I print in the darkroom. Black and white really feels so tangible, and I think that’s why I gravitate towards it. But I couldn’t have come to these conclusions in colour film because it would have taken me much longer. With black and white, I could buy 20 rolls, some chemistry, shoot unlimited, and then instantly develop the film, scan it that night, shoot the next day. That was what I was doing during the pandemic, and there were a lot of breakthroughs.

AM: The last photo in the book comes after the one of your father, it’s a scene on the water, there are people dotted around, and the sunlight is reflecting off the surface. It feels hopeful. Was that your intention?

RF: Yes. I think the book is extremely hopeful in the sense that it is about self-love. I really do think it should be viewed in that way. There is hope and overcoming. Resilience is a strong theme I’m really interested in. For me, that image shows a representation of being at peace or a paradise that hopefully, my father is now at peace and resting and no longer in pain. The beauty of the everyday. A reminder of like, ‘OK, this did happen to me’, but my father would have given anything for more time, and because I have it, I have to do something with it. There’s no giving up for me, and that’s what I try to remind myself.

I can’t stand to see you cry, published by Loose Joints, is available to order here.