What is imparted to an object when it is scanned, and what is imparted to an object when it is scanned by the artist Katerina Jebb? There’s the imprint of labour, certainly – the British-born artist’s technique of flat-scanning artefacts piece-by-piece, before seamlessly reassembling them into a collaged whole, takes many long hours and several days per project. There’s a new clarity: something ordinary and familiar is rendered in high-definition, acutely detailed to such an extreme that it takes a few seconds to correctly name it. And, there’s a revelation of it’s hidden mystery. Jebb – who contributed to the most recent issue of AnOther Magazine – is an analyst bearing witness to the “thing-ness” of things, by which I mean the energy deposited into objects by those who originally made them, those who held them, and, as the artist’s body of work attests to, the audience who look at them in the form of large-scale photo-collages.

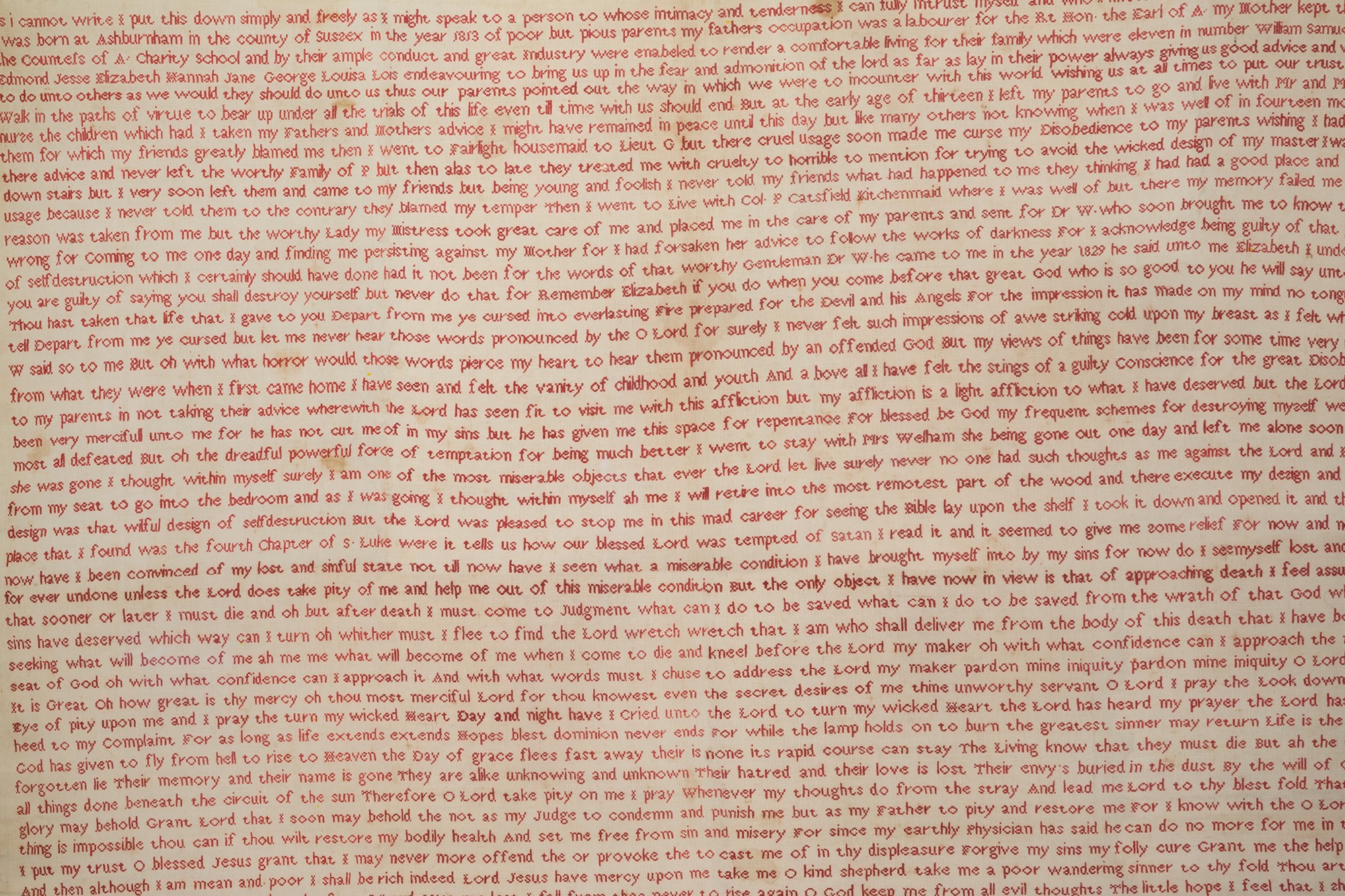

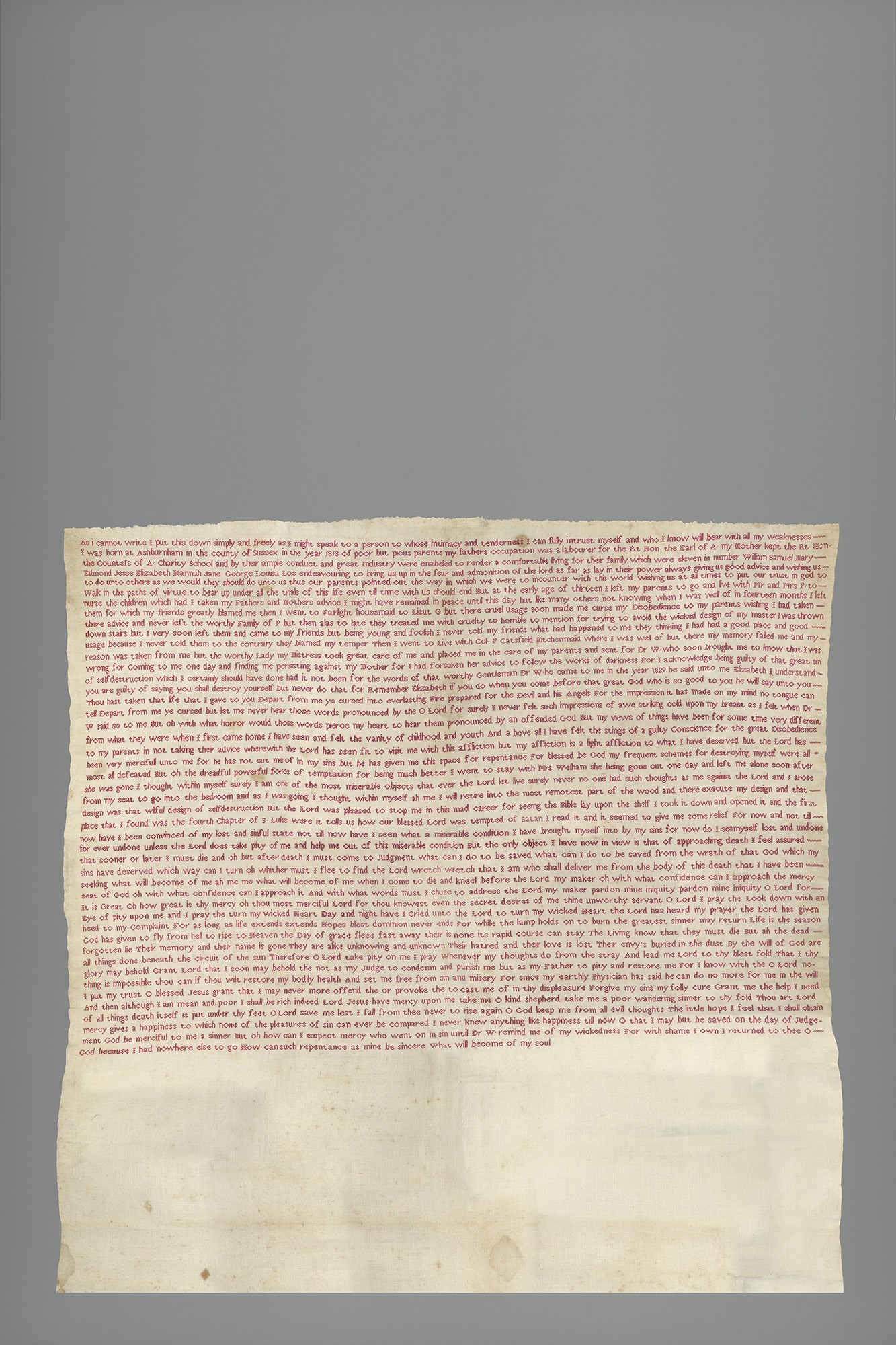

“It’s about the charge,” Jebb tells me over the phone from her studio in Paris. “And me being this forensic investigator. I want to document things that I’m attracted to.” One of her latest projects is a new large-scale photomontage of an embroidery sampler sewn by a late Regency woman – a “teenager”, Jebb emphasises – which Jebb found while exploring the V&A’s archives. In a meeting of the painstaking work of two women across the centuries, Jebb has scanned and re-appropriated this object, but also brought to life the painful story sewn within it. Elizabeth Parker’s sampler, dating from around 1830, is a confession in the form of tiny red thread, detailing the story of her life: one of service, undergoing abuse, and persistent thoughts of suicide. Remarkable in and of itself, it will transform into a kind of monument to the span of this woman’s girlhood and coming-of-age, a bold 2 x 3 metre display of feminine subjectivity, compared with the male-carved goddesses that are also positioned in this area of the museum (the original sampler, which is only 86cm x 74cm, will be on display in the fashion galleries at the same time). For her part, Jebb likes the spot that Katerina Jebb / Elizabeth Parker will be positioned – when the V&A re-opens in May, it will be situated between two sculpture galleries, and Antonia Canova’s The Three Graces is being moved closer by.

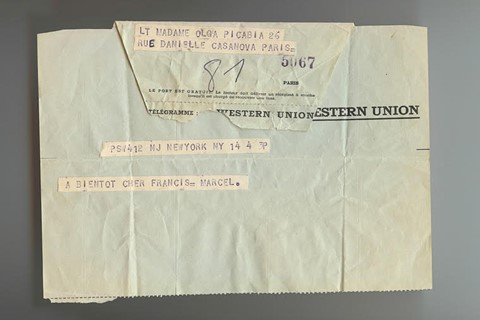

This detail is one that feels appropriate to an artist whose work always represents a kind of tender trifecta; as she describes it, “There’s the scanner, the object and me”. The object of her attention isn’t always straightforwardly such, with Jebb alternating in fascination between physical artefacts, and living people’s bodies. But whether she is scanning the belongings of famous figures like Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, and Balthus, or famous figures themselves – Tilda Swinton, Isabella Huppert, and Michèle Lamy have all been taken apart and re-assembled under Jebb’s technique – what remains constant is that Jebb, like any investigator, is spurred on by mystery. She is not interested in the notion of celebrity; perhaps that’s why she renders it so uncanny.

At the end of our call, Jebb kindly takes some photographs of her studio to send to me. She is surrounded, of course, by stuff – a chain mail suit of armour topped with a fencing mask, child mannequins with missing limbs, her framed Liberation Press Pass from 1989, various rare books for her upcoming window display at Shakespeare & Co – but it feels strange to see these items in their relative three-dimensionality on my phone screen, rather than floating in that other grey haven that only Jebb seems to be able to access.

Claire Marie Healy: I’ve seen images of the Elizabeth Parker installation in-situ – it will be much better to see it in person, though.

Katerina Jebb: It’s like floating language, embroidered, let’s say. I think any work needs to be seen in person. Because a pixelated representation of a work, isn’t really the work is it? It’s divorced from the work, the way that we’re seeing it on a computer or an iPhone. It’s not the same as standing in a place. The V&A is a little bit of a sacred space. It’s probably one of the most loved spaces in England. It’s in our heart. I don’t know how, it’s a sort of unfathomable presence. It’s so English. It represents England, as much as an oak tree or a green field.

CMH: It has this sense of childhood, [like] when you first start going to galleries. It just connects more, somehow, because of the focus on objects. I think when you’re young, and you’re forming a relation to culture and visual culture, that’s a very different thing to going to see paintings.

KJ: It’s like the worship of objects, in a religious comparison – it’s like the object is worshipped, revered, in a very high place. And the V&A is a church: it’s the spirit of it, the richness. Going to church, there’s a ceremony. There’s an importance, let’s say. I think the frequency in there is higher, that’s possibly why it [holds] such an important place in our memories. The frequency is high because of the charged-ness. The charge of all those objects together, all congregating – their energy emitted is probably unmeasurable.

CMH: I was actually wanting to ask you about the energy of these spaces that you move in, museum archives and so on.

KJ: Yeah, that’s really important to me. The energy of spaces, and people. Everything. It’s such an unfinished question about everything.

CMH: When it comes to your encounter with the Elizabeth Parker work, is this you moving through the archival space of the museum, having some free reign there?

KJ: I think it’s me being a private investigator, having that sort of natural attraction to unearthing a place. An interrogation – investigating, looking at what’s in a place, what disturbs me, or what is poignant. Not what’s decorative, because that’s not the important thing for me. That story – that strange, unanswered prayer – is deeper to me than a beautiful, decorative, chinoiserie from the 17th century. Although I would appreciate it, I like this spacious work more. It’s spaciously imaginative, because it makes me imagine: oh, what, how, why? It opens my imagination. And I want work, or anything, to open my imagination. I want to be questioned. I don’t want to be just stroked. If that makes any sense.

“That story – that strange, unanswered prayer – is deeper to me than a beautiful, decorative, chinoiserie from the 17th century” – Katerina Jebb

CMH: There’s something in what you’re saying about the energies of objects. For me, that’s to do with their process of making as well.

KJ: Yes, what’s imbued. What’s imbued in that sampler is all of her chagrin.

CMH: I’m thinking about labour, I suppose. Because when you’re thinking about women in this time, you think of their labour; this teenager putting so much painstaking labour into creating this object, in what I can only imagine were snatches of time. And then I think about the time you have taken doing it.

KJ: The thing is, we just don’t know. We have no idea if she took six weeks, six months or six years to make this. So it posits many questions in the viewer’s head. Which is good. It’s interesting to examine something. It’s forensic – a forensic examination is the way that we’re looking at it, in a cold way, the way the scanner saw it. And I’m the third party.

CMH: And what is the result of your examination – in as far as, what does your technique find out?

KJ: I mean, I didn’t read it properly until a long time afterwards. I react to something trustingly. I trust that this is an interesting thing. And I will properly read it when I’m ready to read it. And when you do read it, it’s what’s between the lines [that draws you] – it’s what she doesn’t talk about. You obviously get the idea that she’s been abused, raped, sexually violated. I mean, something went on. And then the thing about her throwing herself down the stairs. It’s not very explicit throughout – there’s a complete lack of evidence. In a court of law they would just say this is just abstract expressionism. There’s too many open paths. There’s too many possibilities. That’s why we react to it now, 191 years later, because it’s the complete opposite of the mode of communication we have established in the present time. It might as well be a cave painting. Because it’s so far away from what we’re in.

CMH: I felt, reading it, that there is still a slight kind of holding back. But perhaps there’s also a sense that she doesn’t quite possess the language yet to articulate what she wants to express.

KJ: I think it’s a veiled confessional. It’s a very veiled confession. If you read about her, if you go on to make a little bit of research, you’ll find out she didn’t commit suicide, so she did not achieve her goal of taking her life. She carried on living. And she brought up her sister’s child. She was childless, but she brought up her sister’s child. Not so sad of an ending! I mean, we’re all voyeuristic. Even people who say “Oh, no, I’m not interested in other people.” It’s not true because we all naturally have that curiosity to compare, and despair – and look at other people’s lives and look in. We can walk away you know? So there’s no real commitment. It’s fairly easy.

“It might as well be a cave painting. Because it’s so far away from what we’re in” – Katerina Jebb

CMH: Your work being a tribute, in a sense, did make me think of the discussion at the moment around monuments to people and people’s lives – statues, really.

KJ: There’s a big question mark for me hovering over that. Because I’m not quite sure if you can eradicate history, just by eradicating a statue. The fact is that the fact happened – this event did happen. By destroying the statue will it erase that moment in history? No, it won’t.

CMH: But equally, there’s a push for works dedicated to women, and people of colour, who have done incredible things. So maybe it’s about what you replace the statues with, like your tribute to Elizabeth Parker here.

KJ: I think we’re on a precipice. We’re just entering into the real, deep ownership of equality. You know, you can discover technological innovations, but then to master those technological innovations takes another few years – to master what man has uncovered, discovered. I think it’s a similar situation with equality, and rights. Now mankind needs to start to master this newborn consciousness. Which just seems to, happily and very welcomely, be more omnipresent.

CMH: How do you feel the form that public works take relates to this question?

KJ: I think it’s about consciousness. We’re entering into an age of consciousness in a much higher form. The information highway feeds kids information whenever they want. This builds awareness and awareness is linked to consciousness. Things that are revealed and shown in something like an institution – like the V&A. When an institution takes this into consideration, I think then we can say: Gosh, that’s great.

CMH: To see that kind of intervention by an institution into its own archive, too, is encouraging. I love your documentation of the painter Balthus’s studio objects, speaking of a different intervention.

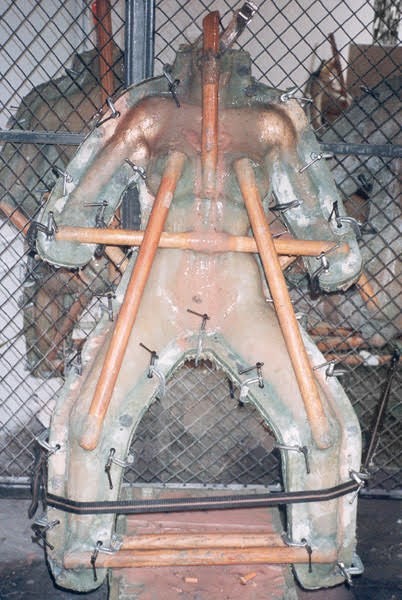

KJ: Balthus, he’s a very mysterious character. When they asked him to write – I think for the Tate or a big museum in London – a comment for an exhibition, he said, “Let it be said that nothing is known of the work of the painter Balthus.” That’s good. I like that. I can really understand that. There’s too much celebrity around artists, around the narcissism of creators. I think it’s best to leave things unsaid, sometimes. I had access to Balthus’s studio for a few years and I just obsessively made thousands of studies of his possessions. Which, one day, may be a book. What’s interesting is this conflict between the object and the human. I’m making this whole window in April for Shakespeare & Company for their rare books, it’s an exhibition about counterculture, and these little studies of conflicting phenomena in counterculture. So I’m in a proper obsessional tunnel of rare books, which I collect. But it’s not just the object that I identify with. I’m also in the middle of making a 50-metre public artwork in Paris. Of 50 women. These are human, all lifesize human portraits, composed of really amazing women. So that’s really the opposite of my clinical cold study of the object, is my obsession with scanning humans. So they’re in conflict, but they’re in polite conflict.

CMH: Sounds very busy.

KJ: Always. The plate’s always overflowing. In a good way – I think that it’s called occupational therapy.

Katerina Jebb / Elizabeth Parker is at the Victoria and Albert Museum, which is opening on 19 May.