Two exhibitions in Antwerp celebrate the enigmatic and oft-overlooked photographer’s singular vision of the theatre of the everyday

The post-war photographic landscape in Japan is defined by two diametrically opposing movements. While the Kompora group pursued reality in a cool, clinical manner, the Provoke collective – founded by Daido Moriyama, Takuma Nakahira at al – who stormed onto the scene soon afterwards in the late 1960s, held their cameras askew for blurred, emotive and radical results.

The late Issei Suda occupies a unique position in Japanese history: a lone wolf at heart, he was never formally associated with any photographic school, and steered clear of the political impulses of his compatriots. While Suda’s unfettered autonomy has come to define his revered legacy in his native shores, it in turn serves as the reason why his oeuvre has been overlooked overseas. Two new exhibitions in Antwerp – Hibi: fragments of daily life at the intimate IBASHO gallery and Issei Suda – My Japan at the sprawling FOMU, the latter the photographer’s first retrospective outside Japan – look to celebrate his unorthodox charm on its own terms.

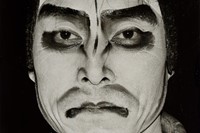

Born in Tokyo in 1940, Suda was gifted his first Rolleiflex camera from his father when he joined the Tokyo College of Photography. Soon after graduating in 1962, Suda began working as a press photographer for the underground theatre troupe Tenjō Sajiki, notorious for their flamboyant fantasy, grotesque eroticism and jet-black comedy. “I am my parents’ only child,” Suda told curator Frits Gierstberg in an interview, published in the FOMU retrospective’s accompanying book. “The most difficult thing for me is to work with other people. So, I worked for them as an outsider.” In spite of the fact it wasn’t the swords or gore that had enticed Suda, but its provocative founder, Shūji Terayama, and his soul-searching stories from the misty mountains of Osore, Suda would never shake off the spell of the stage.

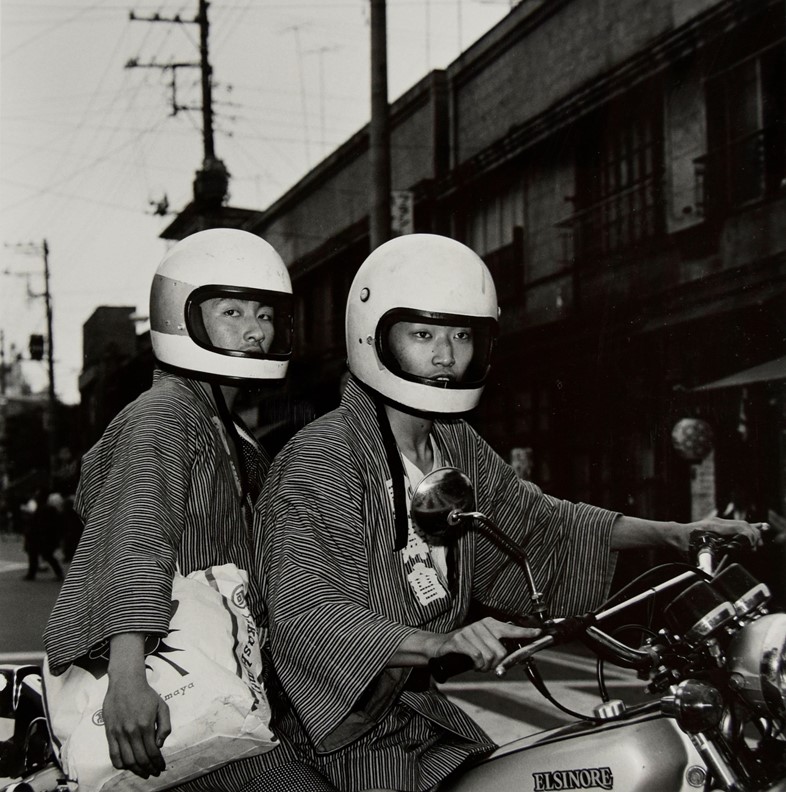

Following his resignation from the troupe in 1971, he embarked on his own spiritual journey, criss-crossing the country to capture, what he called, the “collective madness” of age-old festivals. Zooming in on villagers draped in costumes and caked in make-up, the zestful shots were compiled into his instantly-iconic photobook, Fushi Kaden (1977) – its title a direct nod to a 14th-century treatise by Zeami, the master theorist of Noh theatre. Drawing parallels between flowers, youth and the nature of performance, Zeami had called upon actors to fuse their innermost feelings with outer perceptions to achieve the purest kind of execution: one that revealed and concealed in equal measure.

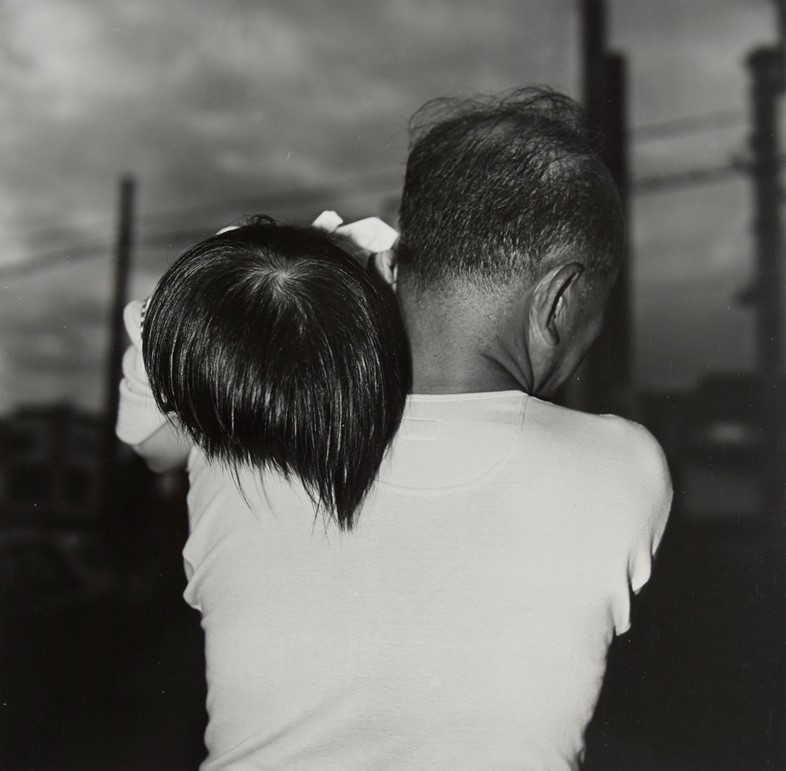

While Suda strived to fine-tune this harmony between inner and outer worlds as he turned his lens from the drama of the coasts to the drama of the cities, he was no nostalgist: with one eye on the philosophies of the past, he had another on the drab sights of the streets at a time when Japan was in the throes of hyper-urbanisation and social unrest. Yet Suda was decidedly apolitical: “I have no particular opinion about contemporary trends and am almost overwhelmed by the changes,” he once said. “Photography is the art of borrowing. The subject always exists in front of us.”

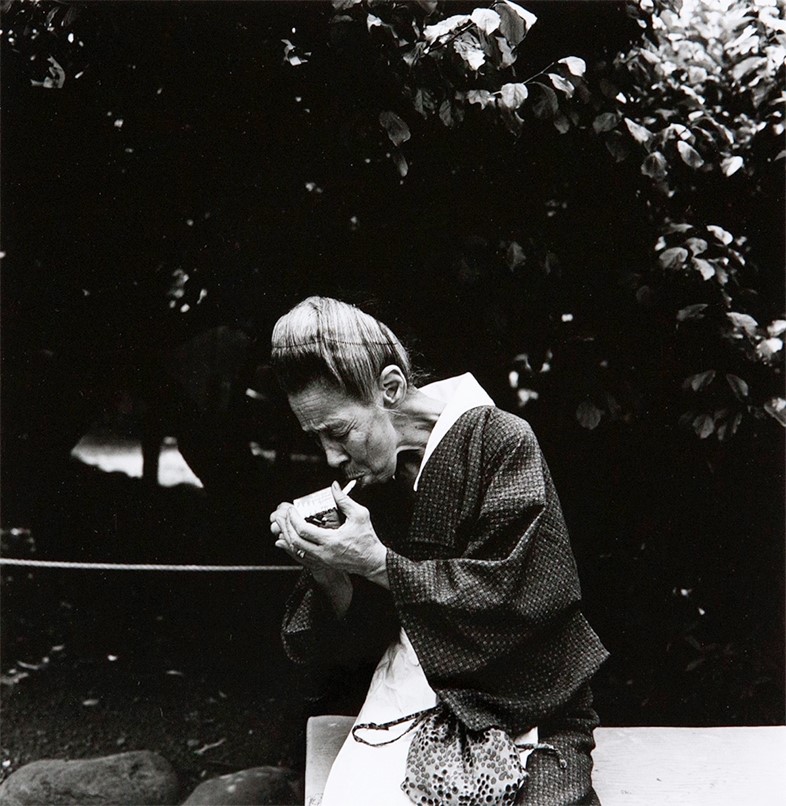

Nothing illustrates Suda’s wide-net throws – an embodiment of the principle of shinra bansho, meaning “all things in nature” – more than the kaleidoscopic textures which throng his scenes. In seminal photobooks such as Waga Tokyo 100 (1979) and Human Memory (1996), we find bonsais, bicycles, billowing kimonos, chugging chimneys, a boa constrictor’s scaly body slithering up a wooden staircase and a yakuza member’s tattooed figure flying through the sky. Grandmas recur too: they carry poodles, light up cigarettes and hop into holes in wired fencing. For Suda, the clash between tradition and modernity, artificial and natural, was not a source of tension, but the new reality.

It is hard to pinpoint what makes Suda’s street scenes so otherworldly, given their ostensibly ordinary subject matter. “My shooting method was once compared to an ancient sword trick in which one slashes his enemy at the same time as he removes the sword from his sheath,” he recalled.

In literal terms, Suda’s sword was in fact his flash, which he often triggered in broad daylight. “It’s a kind of magical formula to me.” Casting the world with his signature-sharp slice of light, Suda sought to pierce reality’s curtain; to give a glimpse into his singular vision of the theatre of the everyday, otherwise invisible to the rest of us.

Hibi: fragments of daily life runs at IBASHO until 6 June 2021 and Issei Suda – My Japan runs at FOMU until 3 October 2021. The latter is accompanied with a book by Fw:Books.