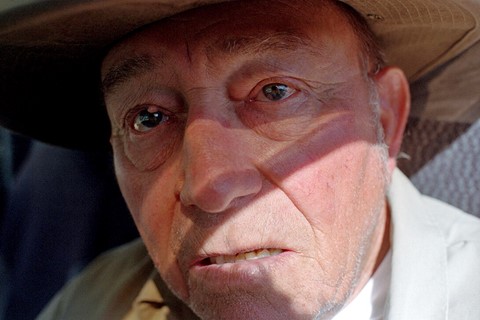

“When I see a train go by I always get this feeling,” says photographer Mike Brodie. “I don’t know what it is, it’s just this interesting feeling. The idea of freedom and adventure … it’s amazing, it’s a very American feeling.”

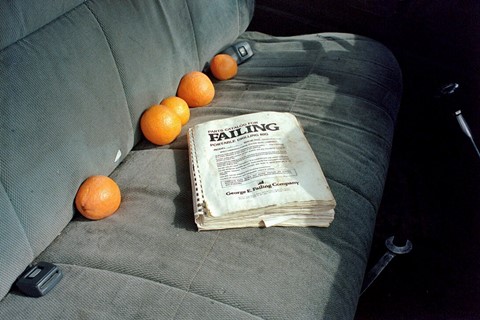

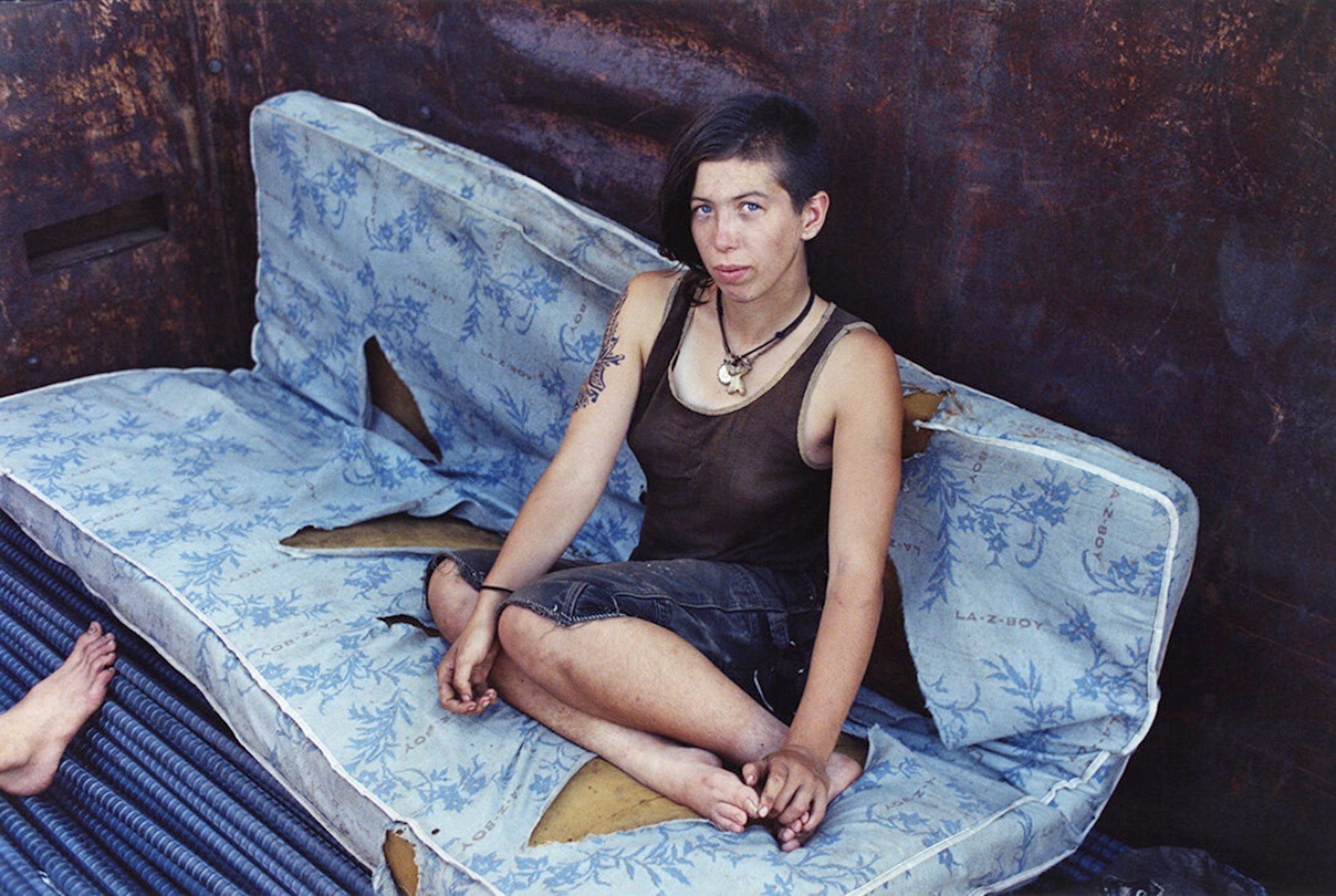

Brodie was 18 when he left home in Pensacola, Florida, to hop freight trains across the country between 2004 and 2008. He was 19 when, after being gifted a camera by a friend, he started photographing the communities that he rode with, becoming a young observer known as “Polaroid Kidd”. His first book, A Period of Juvenile Prosperity, was published in 2013, followed by Tones of Dirt and Bone in 2015, two volumes of vagabonds and outsiders, lost people on a linear path they had no control over – the train tracks.

Brodie’s work was lauded by critics and other photographers, praised for its unflinching depiction of a subculture that audiences recognised as being distinctly American – the savannahs, the filth, the vastness – but had either never seen or were unsure really existed. And then, according to interviews he gave, he stopped taking photos altogether, although today he admits that he wasn’t being entirely truthful. “In reality I never really stopped,” he says. “I think there was an interview that I did where I said I quit photography. So there’s a public perception that says Mike Brodie quit photography, but my camera’s always been around. I didn’t want to be an artist by trade. I didn’t want to be an artist as my career. So I went to diesel mechanic school.”

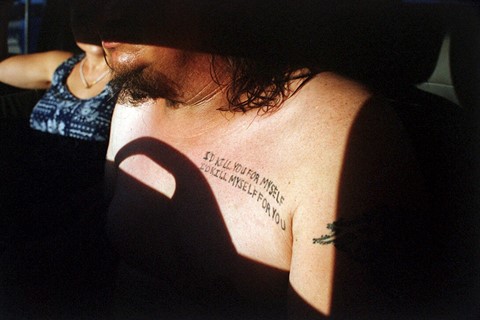

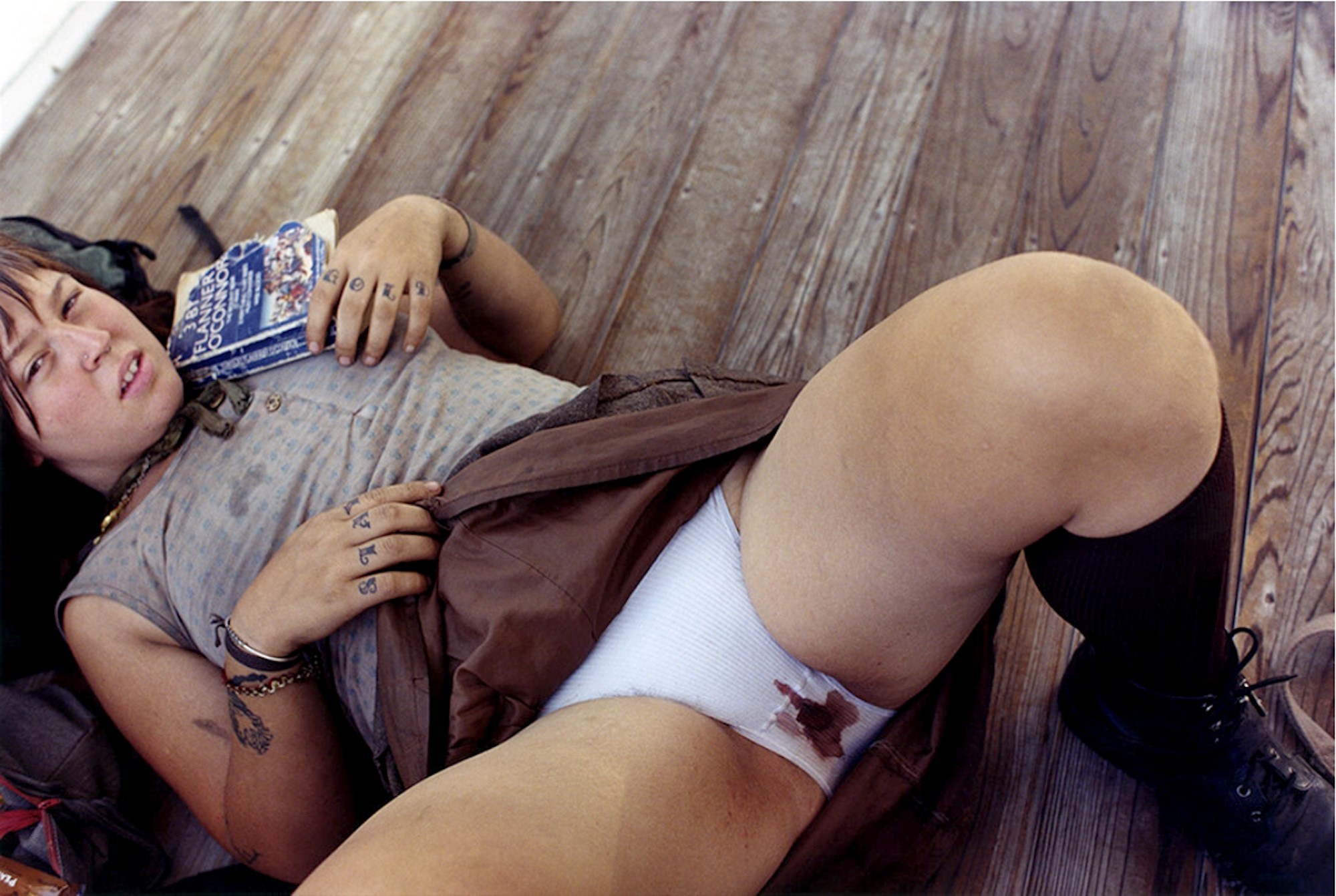

Brodie takes photos that you can’t look away from, photos that you can smell and touch, photos that make you feel like a voyeur with permission. When he set off on the railroads he had no formal training or experience as a photographer, but a clear eye for humanity and the trust of his subjects. It’s no surprise that he talks fondly of the radical punk scenes that shaped him as a person and clearly – despite his protestations that he isn’t one – shaped him as an artist.

Now he runs a trucking company in Nevada, and despite having walked away from train hopping, still considers it a huge part of who he is. I’ve loved Brodie’s work since I first saw it and went back to his photos during lockdown, perhaps summoned by the sense of adventure, of escape.

In 2008, when Brodie was ending a four-year trek across the country, America was at its own crossroads. Obama had just been elected, Shepard Fairey’s HOPE posters were stuck to windows, social media had arrived. I was curious if the American underbelly in Brodie’s books still existed, a land of freedom, decay and endlessness. After a few emails which revealed that he was still taking photos, he agreed to talk.

Thomas Gorton: You’re taking photos again. What caused you to stop in 2013, just after you released A Period of Juvenile Prosperity, and what sparked picking up the camera again?

Mike Brodie: My camera’s kind of always been around, there was just a break in my mid to late 20s. I decided I wanted to get into the trades, I didn’t want to be an artist by trade. So I went to diesel mechanic school. [That] was two years and I was getting different jobs in the industry. That was my priority – working and not doing art. Even though I was still an artist, I was just kind of denying it. The camera was around but the creativity and the inspiration wasn’t there.

TG: I don’t think there are many people in your position who would’ve said, “I don’t want to be an artist, I don’t want to do that.” It seemed as though you probably had the opportunity to go and do it?

MB: You can’t deny whether you’re an artist or not, either you are or you aren’t. I was saying I don’t want to live and work within the industry of the art world, you know? I don’t want to navigate that, that’s not how I want to make a living.

Later I found out that I am an artist and that’s OK but there was a while when I was confused – am I an artist or am I just this guy taking photos? So I was rejecting it for a little while but then I realised, oh it’s OK to be grown up and be a man and work, but then it’s also OK to be an artist too. I just didn’t want it to dominate who I was as a person every day, I just wanted it to be a form of creative expression. It’s still a priority but I’m not going to wake up every day running out with my camera. It was just this identity crisis in my twenties.

TG: You spent a lot of time documenting outsiders in America, just after 9/11 and the invasion of Iraq. Did you get a real sense of where you thought America was at then, politically?

MB: A lot of the energy that inspired a lot of the train riding from people my age – people that I knew, people that I photographed – a lot of what inspired that lifestyle is the politics and music we were listening to that carried over from the late 90s and early 2000s, after 9/11 and the Bush era and the Iraq War. A lot of people that were upset about what we were doing in Iraq and whatever convoluted politics they thought they knew about ... that energy inspired a lot of youth to go hop trains, start punk bands, and personally protest the world in that way. By 2008, when Obama was elected, I had no interest in politics. I think me and my wife voted for Obama, but I was indifferent about it, I just voted because I hadn’t up until that point. 2008 was right when I was deciding I wanted to be a diesel mechanic. So politics were nowhere near something I was interested in. All that train riding directly correlated with a lot of the radical politics that were surrounding the Bush era, if that makes sense?

I got caught up with a lot of punk rockers and crust punks and started hopping trains because I had no direction. Music has such a bigger influence than we realise in youth movements.

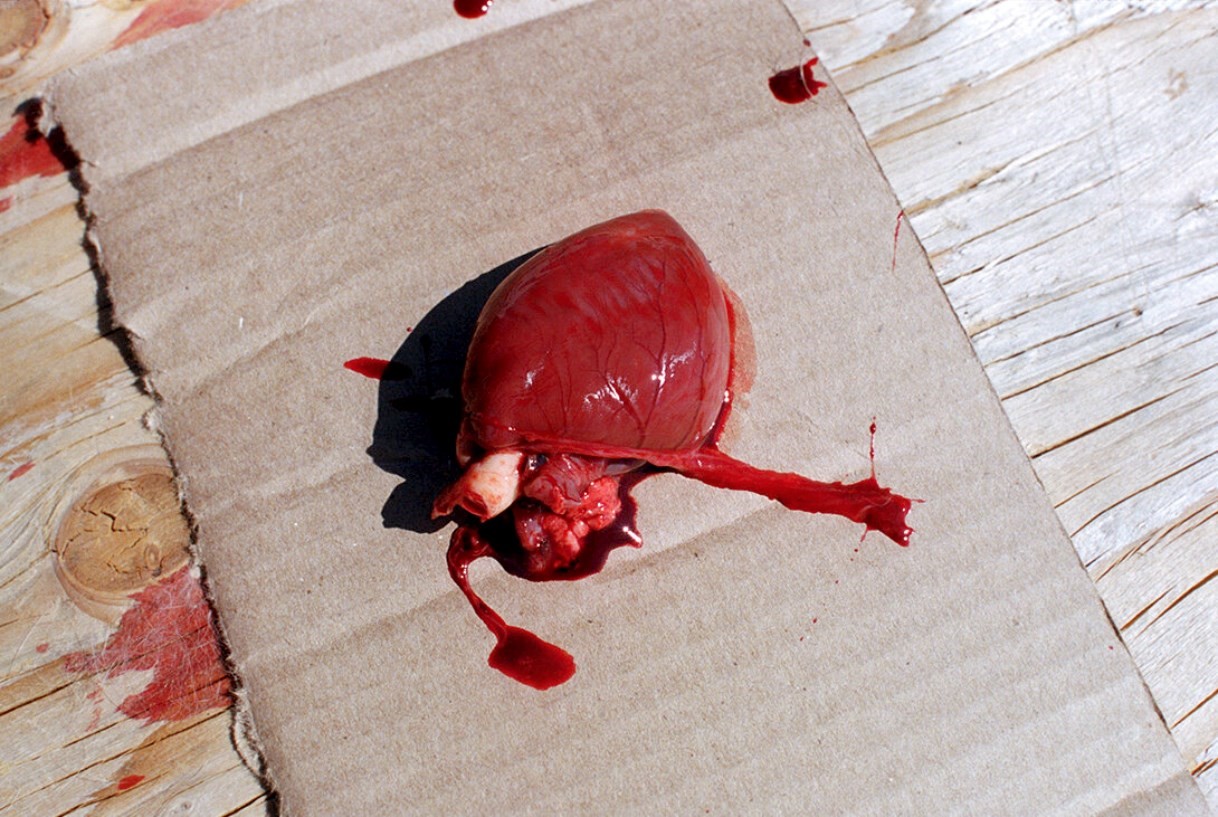

“I’m fascinated by death and I’m fascinated by reality and not just for shock’s sake. It’s just part of our life. To this day it still haunts me and I always wish I just would have run back and photographed the body. I know it’s morbid but it’s life” – Mike Brodie

TG: You grew up spending time in the punk scene before you started hopping trains right?

MB: Yeah it was not very long though, it was probably only a year after that I started hopping trains. I’m talking about radical punk, radical anarchism, not like mall punk with spiky hair. That kind is connected too but it was more like radical anarchists that were in my community, or they at least postured as that was something they believed in. Not everyone was really genuine but it was part of the dress and part of the politics and part of that scene. My girlfriend was punk and she lived in a punk house with all these radical feminists. I just started living there, then I met a train hopper who stayed there and I just got really interested in it. No one took me on a ride, I just went and did it myself.

TG: In the four years you were away hopping trains, what was the wildest thing you saw?

MB: There’s a film photo from A Period of Juvenile Prosperity. The image where there’s a kid laying on coal with a hat on, a couple of people behind him. You can see my hand and my Nike shoe in the foreground.

What you can’t tell is we’re sitting in what’s called the coal porter. Our train stopped and we didn’t know why. We’re on the Florida panhandle riding trains and our train had gone into an emergency stop, it just stopped and we didn’t know why. There were some lights like cops and we just assumed that they were there for us, so we’re hiding, we just think they’re looking for us, and at some point we just get kind of nervous. So we get off the train and as we’re running into the woods a cop sees us and yells at us – he didn’t even care we were riding. He was there to inform us that someone had just committed suicide. A person in rural Florida had gotten in front of the train engines with a shotgun and shot himself.

I’ll always remember that when we were talking with the cop, you could hear on his radio someone saying the serial numbers off the shotgun, because they found the body and the weapon. When we went up to the front engines, of course I was taking photos, I had my camera round my neck and I’m taking photos because there was kind of just guts and stuff on the front of the train. I was taking photos but there was a crime scene investigation person there and she got mad I was taking photos. It was a strange situation but you know the morbid part of me … I always wish I knew there was a dead body under our train because I would’ve ran back and photographed it.

“For me it is a way of life. I still identify as a hobo. Even though the core of my train riding was 2003-2009/10, I hopped a train a year ago. I’m not riding trains full time but it’s definitely something I wear on my sleeve, it’s definitely a part of my identity” – Mike Brodie

TG: Would you have done that, would you have wanted to shoot that?

MB: Oh yeah, oh yeah. I’m fascinated by death and I’m fascinated by reality and not just for shock’s sake. It’s just part of our life. To this day it still haunts me and I always wish I just would have run back and photographed the body. I know it’s morbid but it’s life. It would’ve probably just been some crappy photos, a lot of the time when I have something in my mind that I think is going to be a good photo and I try to go take that photo, it never comes out good. The good photographs are the ones that I never expected, the things that were unplanned, that were spontaneous moments that happen in your life. But still, that experience haunts me.

TG: Your work documents a lifestyle that perhaps many people would perceive as being “every man for himself”, but I think that your photos actually speak to something that feels slightly different, a sense of community.

MB: Really, both things are true. When you travel in that way, it can be every man for himself depending on who you hang out with and there’s a sense of self reliance that you have to have to survive. But there also really is a tight-knit community, specifically in North America, US, Canada, Mexico because we have the most extensive freight network. So that’s why the culture’s so big here. There is a real community there but so much of it is fleeting, it’s very all just a temporary reality because in my opinion, what I’ve seen with my life and my friends’ lives, you can’t live like that for very long.

You can’t live like that your whole life, it’ll kill you. Whether it’s drugs and alcohol or you just lose sense of yourself and what you stand for because you’ve just learned to navigate this economy of living on the streets and getting beer money and visiting friends everywhere, never settling down. It’s not good for you or your mental health but it’s fucking so much fun, you know?

That’s why it’s been so hard for people to document it with photography or film in really realistic, honest ways is because you’ll meet a guy who’s a train rider and maybe you’re interested in his way of life and maybe you want to do a documentary but a year later he’s not a train rider any more. He’s shaved off his dreadlocks and cleaned up his act and now he’s a roofer or something or you know, or he has kids and does something else. So it’s this crazy, really fascinating, fleeting subculture.

TG: Does the subculture still exist?

MB: Yes. I would say the only difference is phones. People want to know exactly when trains are leaving, when they’re going to be arriving, how long it’s going to take, what route it’s going to take – no just get on and ride the fucking train. Bums were already lazy. Now they’ve gotten a little lazier!

For me it is a way of life. I still identify as a hobo. Even though the core of my train riding was 2003-2009/10, I hopped a train a year ago. I’m not riding trains full time but it’s definitely something I wear on my sleeve, it’s definitely a part of my identity.