Content warning: This article contains explicit images.

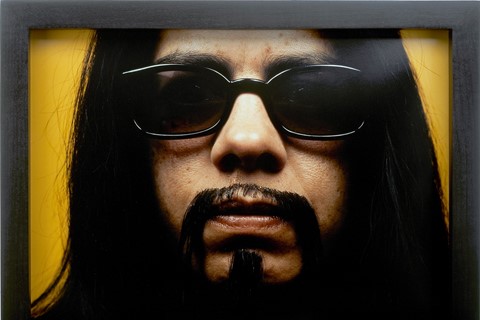

Look at Catherine Opie’s early work and you’ll find images of her sex toy and leather collection, or a beautiful erotic image of a woman standing and pissing, taken for On Our Backs, the cult 1980s lesbian magazine, or Self-Portrait/Pervert (1994), the controversial image of Opie in a leather hood with the word “pervert” carved into her chest. Going on to become one of the art world’s most lauded photographers, by 2010, Opie’s four-part series of Lake Michigan was hanging in the White House.

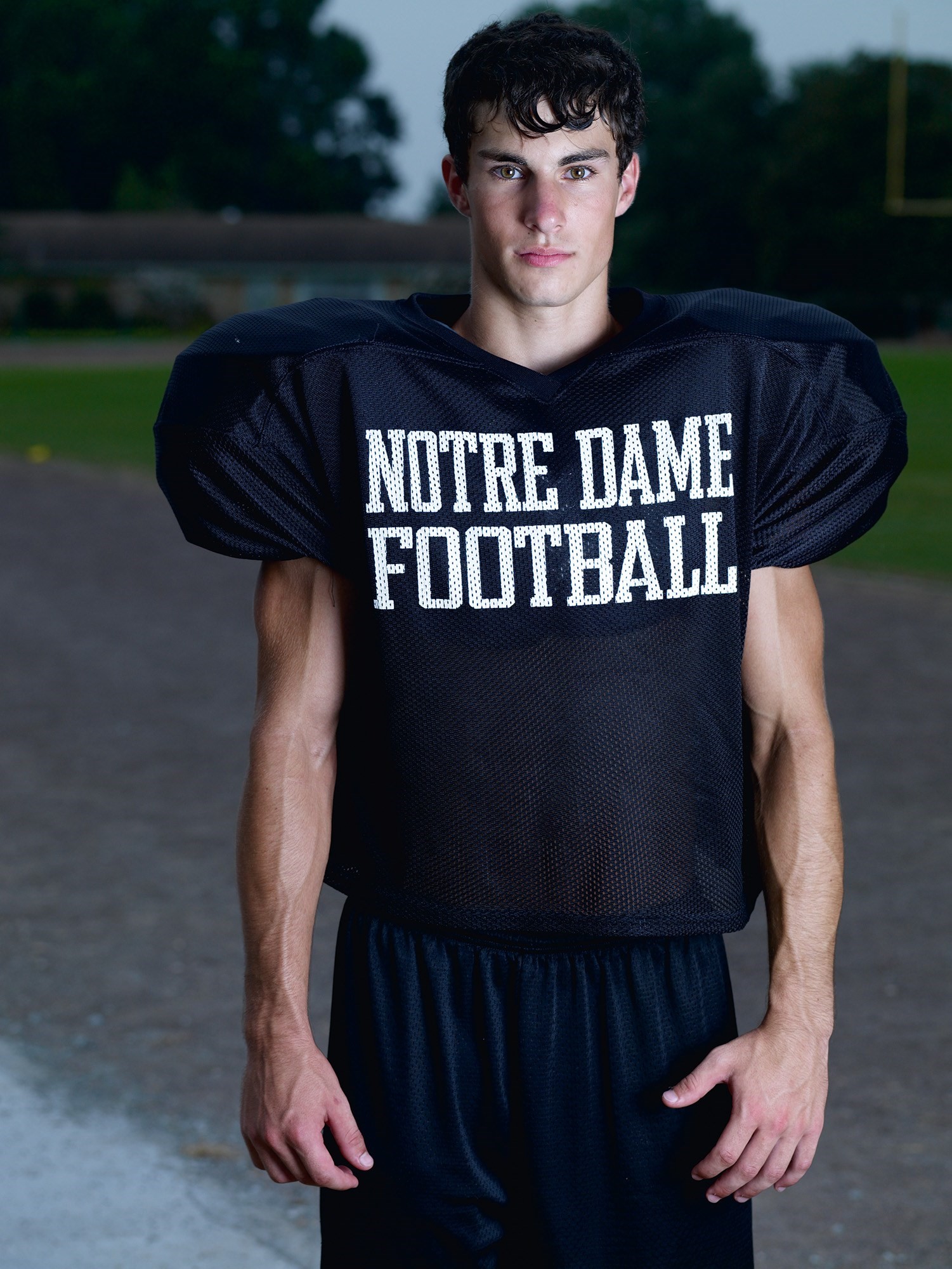

This evolution may seem surprising, but a new Phaidon book of Opie’s work joins the dots between Opie’s portraits and landscapes, her kink and her contemporary protest photography, her work lensing the underrepresented (think leather dykes) and the overexposed (Elizabeth Taylor). From her images of American iconography like freeways and mini-malls, to portraits of surfers and high school footballers, Opie has consistently served us subjects that we might think we know and asked us to look again, which earned her the moniker the “All-American Subversive”.

Below, we talked to Opie about the new book, “no kink at Pride”, and her latest work.

Amelia Abraham: Hi Cathy, can you tell us about the book – why now?

Catherine Opie: Other books have been connected to museum exhibitions. When Phaidon approached me I was looking to do a larger-scale book that wasn’t related to an exhibition, but related to what I thought about as a photographer. I was really ready for the images to talk to one another. Phaidon had actually come up with the categories: People, Places and Politics. By presenting those three specific sections [rather than chronologically or by series], I feel like the book shows the complexities of the ideas in the work in a different way.

AA: Definitely. One thing that really comes across – when you look at all the images, spanning your whole career – is your sociological interest in what makes us who we are.

CO: I think that one of the things that the work has always done is deal with iconography, and this idea of cliche in relationship to it. I always think that cliches can be unraveled and we can look more humanistically than, say, the quick assumptions that we place on people. And that’s not only to talk about my queer community, but even young men. For example, my images of high school football players show how being a football player is not the sum of who those young men are.

“My images of high school football players show how being a football player is not the sum of who those young men are” – Catherine Opie

AA: You’ve said in the past that you had to build up to photographing your own community. Why was that?

CO: I did have to build up to that. It was the 80’s and even though I was out, and I would photograph for On Our Backs magazine and I was always very political, I didn’t necessarily show that side of me as a student, because quite frankly, I was really worried about whether it would affect me getting a teaching job. My aspirations were academia. But it was because of what was happening within that time period in my community, in terms of Aids and the demonisation of queer people, that I decided, no, this is too important.

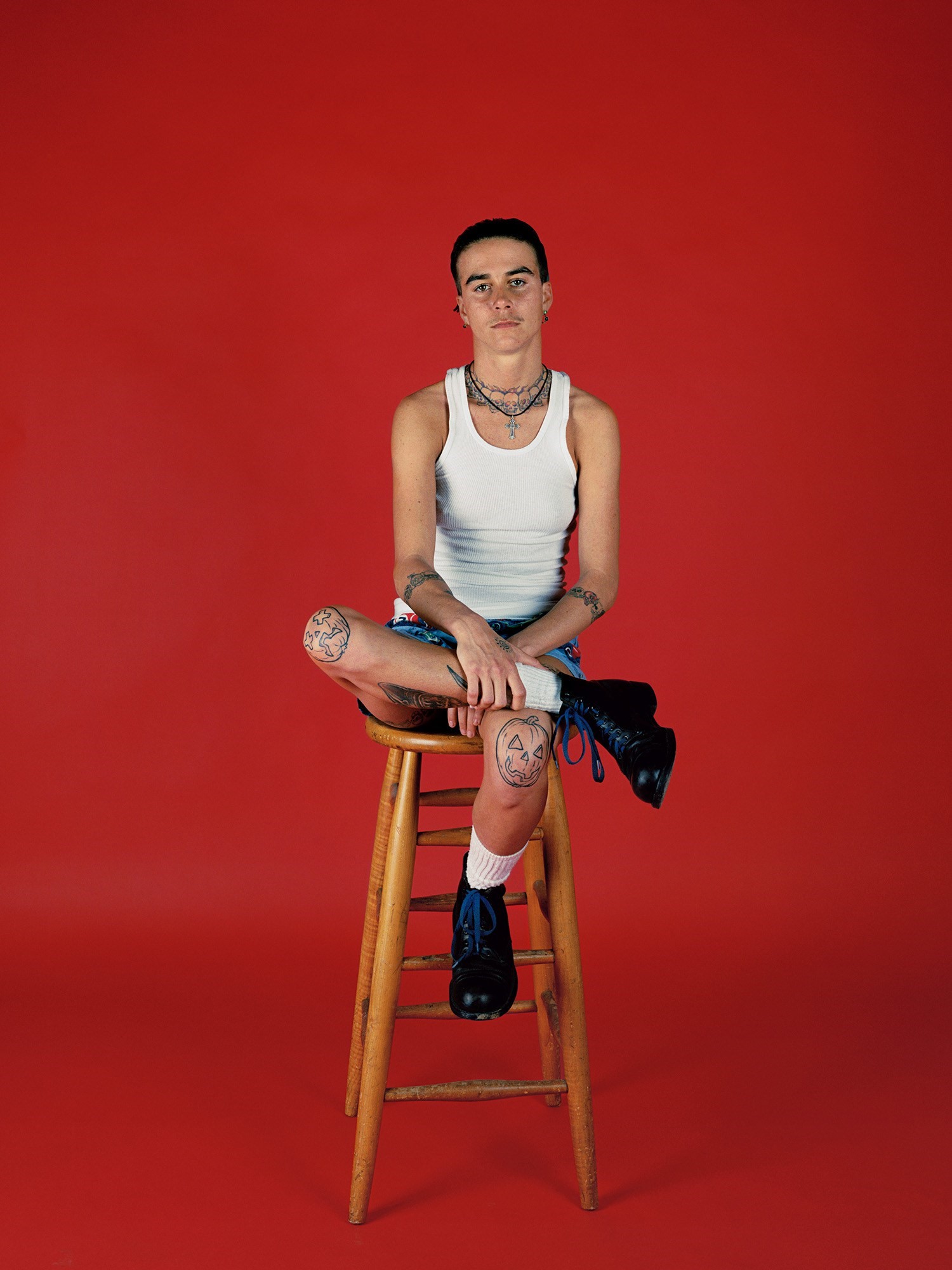

When I made Being and Having I knew I wanted to make work that related to a documentary practice, but take it out of the documentary practice where friends are photographed in their homes. Like, what else can we do to the site of the body? I found that bringing people into the studio also helped me to really engage with how I wanted to think about being a documentary photographer. Even though there were friends that were transitioning at that point, a butch identity or trans masculinity was still often something that was really performed in the clubs. It was the drag king shows, it was us putting on mustaches and going to the bars and trying to offer rides home on our motorcycles to women that we might meet. (They were very confused about that here in LA compared to San Francisco!) So I was interested in capturing this kind of performative aspect for the female gaze. In terms of the camera, through this odd cropping, the choices of the moustaches, the consistency of the yellow background, and the direct gaze back – all of that was not just thinking about the performative nature of masculinity but also desire, and trying to change the way that we think about it, as well as the relationship between humanity and play. I mean, the plaques with the nicknames under the photographs are funny to me. Like “Oso Bad”. So there’s a wit and a sense of humour within the work.

“My aspirations were academia. But it was because of what was happening within that time period in my community in terms of Aids and the demonisation of queer people that I decided, no, this is too important” – Catherine Opie

AA: In 1998 you then took your RV on a journey across America and shot Domestic, of lesbians in their domestic settings. I get the impression that you were compelled to go on that journey to find your own domestic representation.

CO: I remember when I came out to my dad his biggest upset was that he wouldn’t be able to walk me down the aisle. Like I remember him saying, “How are you gonna ever be able to have kids?” So I was always driven by all these initial questions [about family, from looking at what] happened within my own family and knowing that I wanted to have a partner and family from a very young age.

The 1993 Self-Portrait/Cutting on my back was about this relationship [of queerness] to domesticity. That was really the catalyst for the body of work for my MoMA Exhibition, curated by Peter Galassi, Pleasure and Terrors of Domestic Comfort. The idea that domesticity was only a heteronormative experience or at least, that is what is imaged, felt wrong to me. So a lot of times I make work because I also want to be able to correct the history of representation. And by making it myself then it automatically, fortunately, ends up being part of a larger discourse of, “there’s a lot of ways to look at family”. That’s why it was really important in Domestic that it wasn’t just lesbians together with a kid that I photographed, but also households with, say, four young queers living in a domestic setting … to show that’s just as viable a notion of family as like two women who chose to have kids and have a family that way.

“So I was always driven by all these initial questions that happened within my own family and knowing that I wanted to have a partner and family from a very young age ... The 1993 Self-Portrait/Cutting on my back was about this relationship [of queerness] to domesticity” – Catherine Opie

AA: I wondered if you saw these debates blowing up online again last month, about “no kink at Pride” – this idea that kink doesn’t have a place in Pride events?

CO: Well, that’s why I carved “pervert” on my chest. That’s literally why I made Pervert in 1994. There was a division in my own community then, around the March on Washington, where [some LGBTQ+] people were like: “We’re more normal!” What is normal anyway? The binary of normality and abnormality, it’s a psychological assignment on our bodies in relationship to how we live our lives. And that is a problem. It’s a problem that within our own community, there’s a conservative push to assimilation. I mean, I’m really happy to have the right to marry. And that’s because we should have the right in terms of legality. I watched friends, families come in and take everything away from the partner because they had no legality after they died from Aids-related illnesses, or you couldn’t be next to the partner’s bedside as they were dying in the ICU. So having equal access to those rights is what’s important for me, not assimilating into what marriage stands for as an institution. It’s about my partner having the same legal rights for what we’ve built together.

AA: The book includes images from the series Political Landscapes – photographs you’ve taken at various political events, from President Obama’s inauguration to Tea Party rallies. There’s also a great Q&A with Charlotte Cotton and she points out that you don’t “demonise or polarise”. I completely agree. Neutrality would be the wrong word … But how do you make sure that you don’t demonise or polarise?

CO: I agree that “neutrality” isn’t the right word. I think the right word for me is “humanity”, that if we don’t deal with every aspect of it, whether I might have a political disagreement or not, that if I go into a Tea Party rally and I only make them look horrible through the position of the camera, then what kind of position is that versus just bearing witness? I really look at this notion of bearing witness as an important aspect of humanity and of understanding the complexities of actual human rights. I call them political landscapes because they are a moment in which people are gathering publicly to protest or to listen to their same kind of ideological viewpoint and I think that that is important in relation to democracy. Humanity and democracy have to be linked in some ways, and I think that’s what I have tried to do, to a certain extent, with the various bodies of work that I dip in and out of.

“I really look at this kind of notion of bearing witness as utterly an important aspect of humanity and of understanding the complexities of actual human rights” – Catherine Opie

AA: The book goes up to 2020 … to your images of Black Lives Matter protests after the death of George Floyd. What have you been shooting since?

CO: After Black Lives Matter, I realised that I was getting most of my news from photojournalists. I’ve always protested for things that I really believe and I decided that I needed to go and bear witness myself. And so I made a body of work called 2020. They’re all going to be diptychs. One image, for example, is of a monument in Richmond Virginia, of Stonewall Jackson, that was removed. One is from the debate with Mike Pence with the fly on his head. I’m really interested in questions around representation. It’s also really about what has happened in America in terms of these monuments and white supremacy, especially after George Floyd. And the reckoning of having Trump as our president.

AA: What is your relationship to landscape photography as an art historical tradition, one that is based on the white male colonial gaze?

CO: I think one of the things that’s really interesting to me is why is it that women photograph in the studio, predominantly, and men go out and capture this nature? I think that I was dealing with the traditionally masculine landscape position when I was shooting Ice Houses and Surfers by literally flipping it from a horizontal perspective to a vertical and then keeping the horizon line in the middle. And so then it became a fractured landscape. Or when photographing Yosemite and abstracting and playing with it from an Ansel Adams position, which is a beautification and also preservation. But do we need landscape photographs to preserve landscapes or remind us when we don’t have landscapes anymore? I think a lot about that, like with the recent images of swamps in Rhetorical Landscapes (2020) – that is not only about the language of Trump in terms of “drain the swamps”, but it’s also to do with how, because of climate change and global warming, the swamps will be underwater. We will be losing things. And so in the same way that I lost my friends through Aids and cherish the portraits I made of them, I think the landscape is something that we need to be reminded about and bear witness to.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Catherine Opie with essays by Hilton Als, Douglas Fogle, Helen Molesworth and Elizabeth AT Smith and an interview by Charlotte Cotton is published by Phaidon.