Hatty Nestor looks back at the British photographer’s 1997 series and its relationship to the representation of working-class people

The depiction of class in visual culture has always been a point of contention and complexity. One example of this is Benidorm, a once small fishing village on the east coast of Spain which, over the last half a century, has become the home of the tacky ‘Brits abroad’ trope. Although a popular destination for British people on their holidays or in retirement, cartoonish mainstream representations of the town – thanks to TV series like Benidorm on Netflix – have seen it become increasingly entangled with problematic class cliches.

Growing up in a working-class family in Essex during the 1990s, Benidorm was, for me, both a desirable holiday and retirement destination and a working-class slur for ‘tackiness’. While we have culturally become accustomed to stereotypes such as the ‘Essex girl’, which refer to a gendered socio-economic position in society, or the legacy of the derogatory term ‘chav’ for those who live in council housing, the photographic documentation of leisure and class examines who has access to travel and social mobility.

So how have photographers influenced and captured working-class leisure and culture? Across four decades, the British photographer Martin Parr has consistently documented working-class culture in Britain and beyond. From The Last Resort (1975-1982) through to Common Sense (1995-1998), and Small World (1990-2007), Parr has archived the breadth of British identity at home and abroad in an array of photography series, which are as satirical as they are brightly hued.

Parr’s Benidorm series (1997) raises questions about the representation of working-class culture, where satire is intertwined with the politics of leisure. The beach and Benidorm have always been a site of fascination for Parr: “I got obsessed with the resort, and just wanted to come back and build the folio of images,” he says. Despite the project’s “tacky” reputation, he doesn’t percieve it as such, and even produced a series for Vogue España appropriately titled I love Benidorm by Martin Parr.

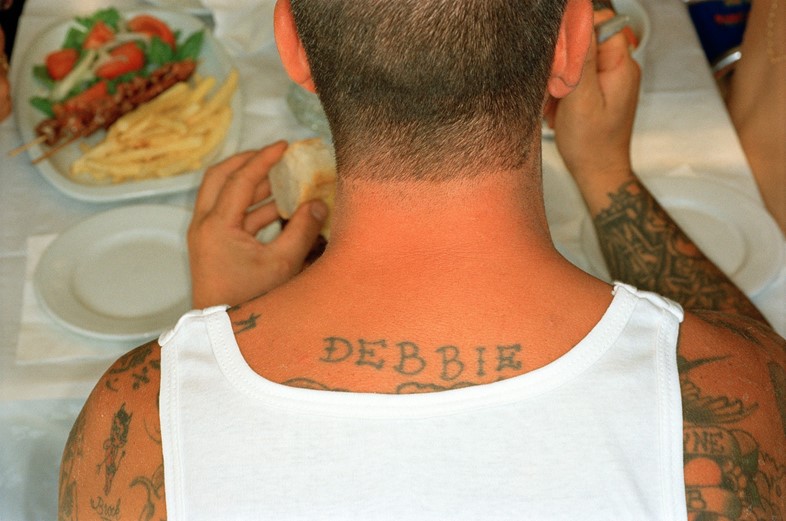

Blue towels, seas, skies, sunburn, fried eggs, and menus of chips and sausages proclaim Benidorm as a home abroad for UK expats. The series encapsulates a quintessential Britishness – through cuisine and attire – which acts as a portrait of accessibility for retired individuals to lose inhibitions and relax. But Parr writes that class was not within his frame of reference when creating the series: “I was totally oblivious to class, and remember there [being] four or five times more Spanish people in Benidorm than there [were] British,” he says.

I often return to the Benidorm series when reflecting on my background and the aesthetics of working-class culture. Yet this slippage between familiarity and satire as a political gesture is what draws me to the series; the men and women photographed in stark vivid reds and oranges could be one of the elderly couples I knew on my estate. Parr explains that photographing retirees is simpler as a photographer: “It’s easier and more rewarding to shoot older people,” he says “They have more character. I did do some club scenes, but it is really a lot more difficult to come away with a strong photo.” The ultra-vibrant colours render the atmosphere somewhat melancholy and detached from reality. The Benidorm series offers a meditation on real and imagined class ideas in this careful realm of caricatures and starkness.

Today, the Benidorm series exposes that perceptions of class are often heavily influenced by our outdated cultural tropes and stereotypes. As the Netflix series Benidorm demonstrates, there remains a nostalgia for the tacky ‘Brits abroad’ stereotype, even if it is becoming outdated. It is also not necessarily in-keeping with other increasingly popular destination trends, with locations like Magaluf and Ibiza moving into the spotlight of class cliches. Parr’s vibrant, pastiche images demonstrate that the archives we create visually of class and culture reverberate and mold class consciousness through future generations.