Comprising 415 found photographs across three eras, a new book from artist Cai Dongdong provides a parallel picture of a nation in flux

Though learning his trade as a portrait photographer while serving in the People’s Liberation Army in the 1990s, Chinese solider-turned-artist Cai Dongdong soon scrapped formalities. Today, he is known for riffing on Dadaist impulses (à la Marcel Duchamp and Kurt Schwitters) via what he calls his “photo-sculptures,” in which he pierces found photographs with arrows, spades and so on.

Cai Dongdong can thus often be spotted sifting in flea markets, public libraries and trash heaps in search of photography to play with. His new book, History of Life, is the result of an epic editing down of 600,000 snapshots into 415 (for every one included, some 1,500 were excluded). “My selection process was uncomplicated and swift,” he shares. “The decision to keep a photograph was based entirely on my intuition. Briefly glancing at an image comprises my visual experience of judging it … Overall, it took six years. The entire process was one of slow growth.”

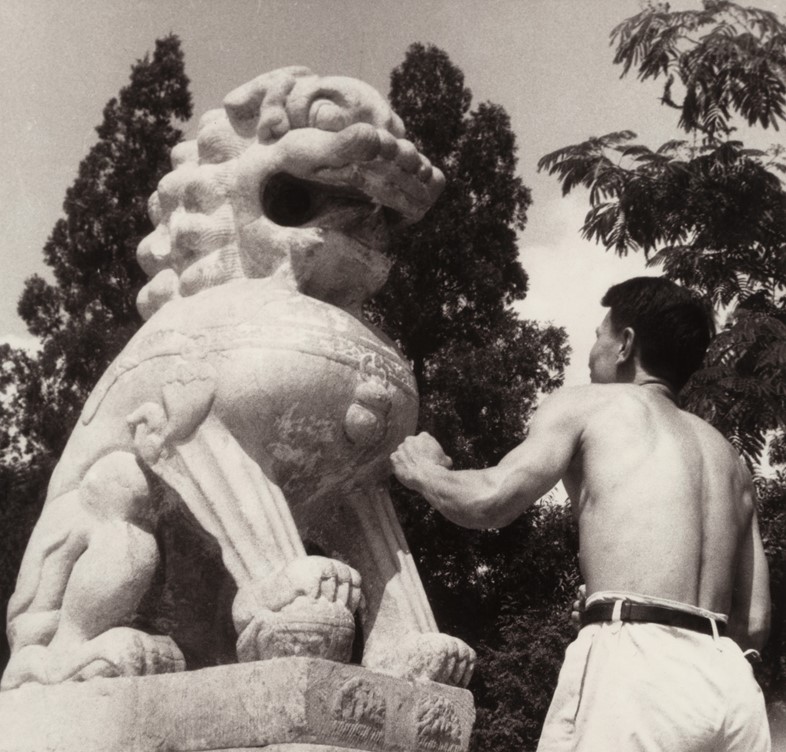

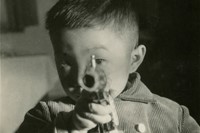

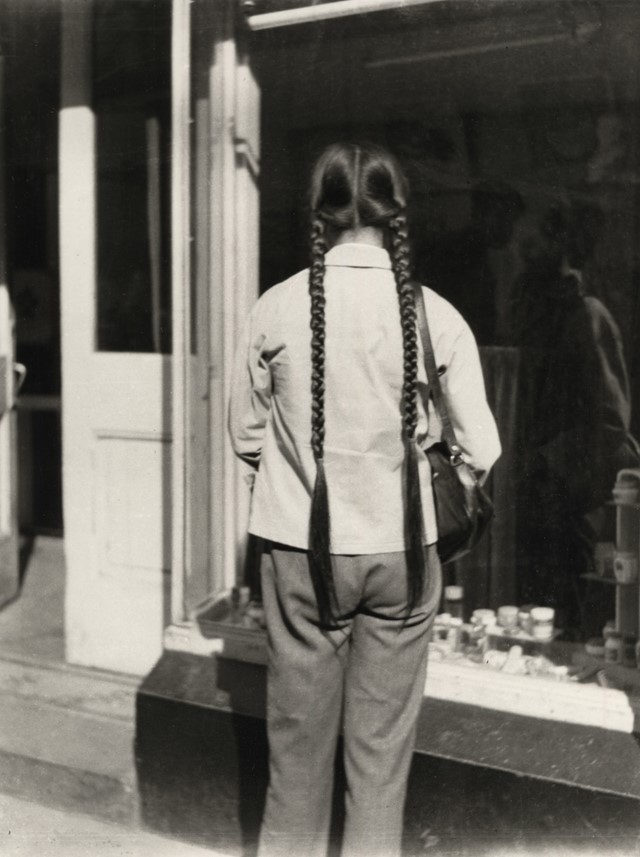

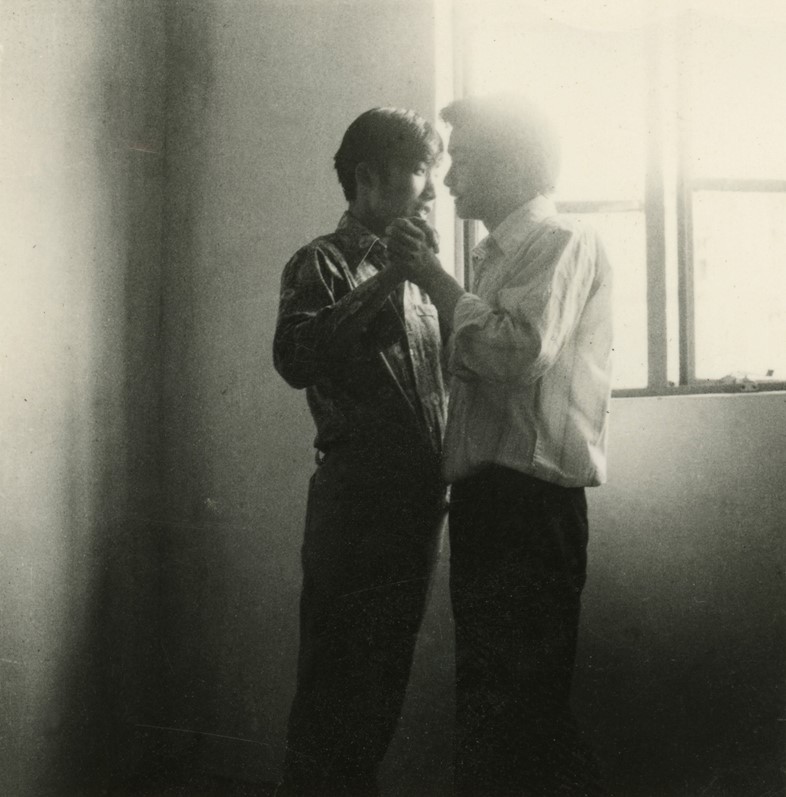

Awash in sumptuous sepia tones, Cai Dongdong’s tome tells the story of the 20th century in three roughly-edged chapters: the founding of the Republic, the Cultural Revolution and the “opening up” period. But, while chronology is a guiding force here, Cai Dongdong’s masterly edit is also supple in that it’s willing to abandon strict sequencing in favour of visual threads. Coupling hitherto unrelated fragments from faraway histories – childbirths and bike-rides, weddings and arm wrestles – each spread, quite miraculously, thrums in melodious euphony.

Oftentimes, the political creeps into the private: schoolkids salute while elsewhere a lonesome Red Army hat sits atop a pile of folded blankets. Yet, without a parade or Chairman Mao poster in sight, it can be said that Cai Dongdong was, instead of pursuing a panoramic account of history, after something more akin to a feeling. “The people’s spirit during each era was very different,” he notes. “The construction of memory and history is neither complete nor precise – rather, it’s imaginative or allegorical.”

With dates never detailed, we’re left with sartorial clues to decipher the timeline. Mandarin collars and cheongsams are eventually replaced by western-style suits and even a top hat. Cai Dongdong also observes stylistic trends in family portraits: during the Republic, hair was “full of product,” he says. “From the 50s to the 80s, people’s demeanours were serious. But from the 80s onwards, people started to look more vivacious.” Yet the book also attests to continuity as much as change: the appearance of a shadow selfie reminds us that the trope is as old as the medium itself.

Cai Dongdong maintains that this work is not as much of a departure from his practice as it may seem. In the spirit of a true “photo-sculptor,” he has sustained his proclivities for “piercing” photographs; this time, not with spades but with his own snapshots, which are mysteriously and seamlessly scattered throughout these pages for “the sake of continuity,” in the artist’s words. By way of these interventions, Cai Dongdong flies in the face of the concept of authorship, in turn embracing the democratic virtues of vernacular photography by proffering a “people’s view”.

History of Life is, to date, the closest rival to Thomas Sauvin’s Beijing Silvermine, a colossal collection of souvenir snapshots salvaged from a recycling plant in the capital’s outskirts. The bulk of the 850,000 negatives narrate the economic expansion of the 80s and beyond, with markers of modernisation abound: proud consumers pose with fridges while McDonald’s signs inevitably land from the west.

The emergence of this freewheeling capitalistic circus, however, signals the wrapping-up of Cai Dongdong’s deft chronology. His is a portrait of China that circumnavigates the political prism through which the country is so often viewed. Yet the title of the book, History of Life – not, say, “History of China” – suggests that the essence of this collective tale is even more transcendental altogether. What we call “history” – so vast and supposedly unknowable – is never so far away from the flickering moments of beauty that populate each passing day, year or, indeed, century.

History of Life, published by Imageless, is out now.