“Zurbarán has been my obsession since I was a little boy,” the legendary designer tells Susannah Frankel in the pages of AnOther Magazine Autumn/Winter 2021

This article is taken from the Autumn/Winter 2021 issue of AnOther Magazine.

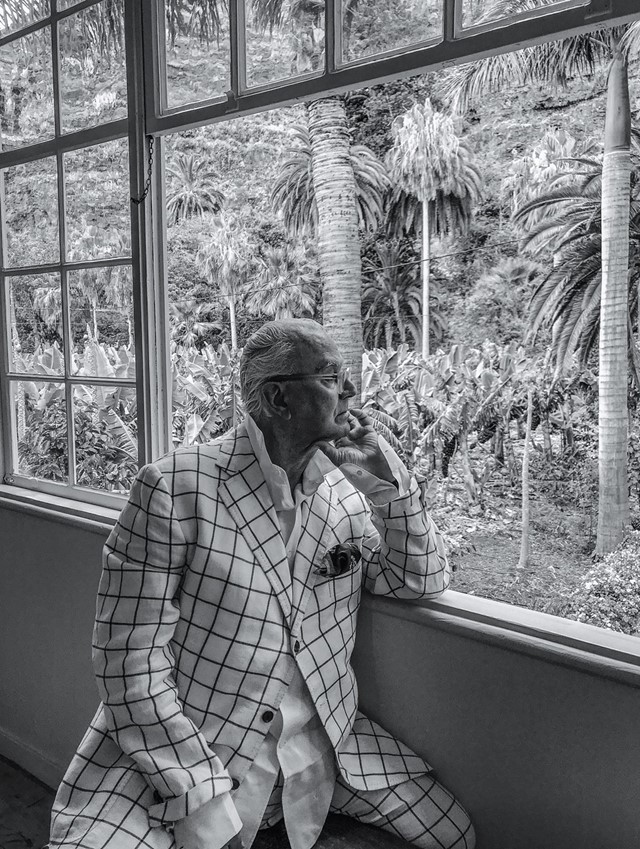

Manolo Blahnik celebrates the 50th anniversary of his business this year. The most feted shoe designer of our time, his work has been exhibited in major international museums and purchased by discerning women for half a century. After growing up in Santa Cruz de la Palma in the Canary Islands, he studied law and literature in Geneva, before moving to Paris in 1968 and then to London, intending to pursue a career in set design. In New York in 1969, he met Diana Vreeland and showed her his portfolio – she told him to make shoes, which he did. Vreeland went on to wear paper-flat pumps that he designed especially for her for most of her life. Between then and now, Blahnik has made shoes for everyone from Ossie Clark and John Galliano to Vetements, and has dressed the famous feet of Bianca Jagger, Tina Chow, Madonna, and Rihanna, with whom he has also collaborated. In 2005, he designed the shoes for Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette. A true – and truly refined – aesthete, he shifts effortlessly between languages and trains of thought, staccato, at great speed. “I am a victim of culture, I was born like that,” Blahnik says. “When I see a painting it’s like I am that painting. When I’m reading a page, I am the page.”

“Zurbarán has been my obsession since I was a little boy living in the Canary Islands. You know, when you’re small they take you to church on Sundays and, in Spain, they love Murillo, which is camp – horrible, tacky. But I kept with me my postcards of Zurbarán’s Saint Bartholomew almost in agony [1632]. I had about ten of them.

“We used to travel by boat to get to school in Geneva or to get my sister to school in Germany. And we always stopped in Cádiz, where there’s the wonderful Museo de Cádiz, which has an incredible collection of Zurbaráns. I must have been about 13 by then, or even 15, and what a revelation it was. Every time I passed by Cádiz for whatever reason, I went there. It was wonderful – Zurbarán seemed like second nature to me by then.

“Later on, my mother took me to the Prado in Madrid, and I always wanted to stop when I saw a monk by Zurbarán, with his eyes looking up to the heavens and his mouth open, almost as if light were coming out of it. The light is like Josef von Sternberg’s light. In retrospect I realise that von Sternberg was totally copying the light of all the old masters and copying Zurbarán especially. It was that light that attracted me – the light but also the hands, the sandals with the dirty feet. So beautiful. There’s one beautiful Christ on the cross too, which is in Chicago. I sometimes do these personal appearances and for one I went to the Art Institute of Chicago and saw it there. I thought, ‘My God.’ I returned the next day and took photographs of the painting with my phone. That Christ is fantastic. The top of the body, nailed to the cross, looks dead, but the hands, the legs, the feet are alive. In Spain that painting is not very well known. I always get surprises with Zurbarán and I have been following him, and have been followed by him, forever somehow.

“He influences my work. Not all the time, but often. The stiff materials I use sometimes, religious materials, heavy wools, tweeds – I love the austerity of those things. Then there’s my interest in the 18th century, which I have also always been very receptive to – those manners. You can read Saint-Simon and on each page you can imagine a shoe. Zurbarán is very pure, very austere. The 18th century is not very practical but I love that too. I am kind of deranged in a funny way.

“When I had an exhibition in London with Mr Conran, at the Design Museum in 2003, the National Gallery lent me Saint Margaret of Antioch [1630–34] by Zurbarán. Can you imagine they gave that to us? And in 2017 we did this exhibition at the Hermitage in St Petersburg. It was the first time a man of shoes opened a show at the Hermitage and it was divine. I saw written on the front of that building from far away, ‘Manolo Blahnik’ – huge – and I thought, ‘Oh my God.’ There was a room there with shoes influenced by Zurbarán and also by Goya, Picasso, Matisse, Mondrian. I’m talking about Zurbarán because he’s my favourite but I love all the tenebristic painters and the modern masters too.

“I love the exaggeration, the theatrical part of the people in Spain. And, you know, they’re unreliable, completely out of their minds, totally living a fantasy. I am a mixture, a cross, a bastard. My father was Czech, my mother super-Spanish. As I get older I see myself very much as a Spaniard. Still, England has a kind of exotica for me that I think I was always pursuing. Zurbarán is totally Spanish. Balenciaga was really, really influenced by him. Zurbarán was like a peasant – in his paintings you can feel Seville, southern Spain, that is what he captures so well. The earthiness, the colours – nobody can touch that colour. And the beauty of the human soul.”

This article originally featured in the Autumn/Winter 2021 issue of AnOther Magazine which is on sale now. Head here to purchase a copy.