With a solo exhibition and accompanying monograph launching this month, American photographer Michael Bailey-Gates discusses collaborating with friends and the pursuit of joy

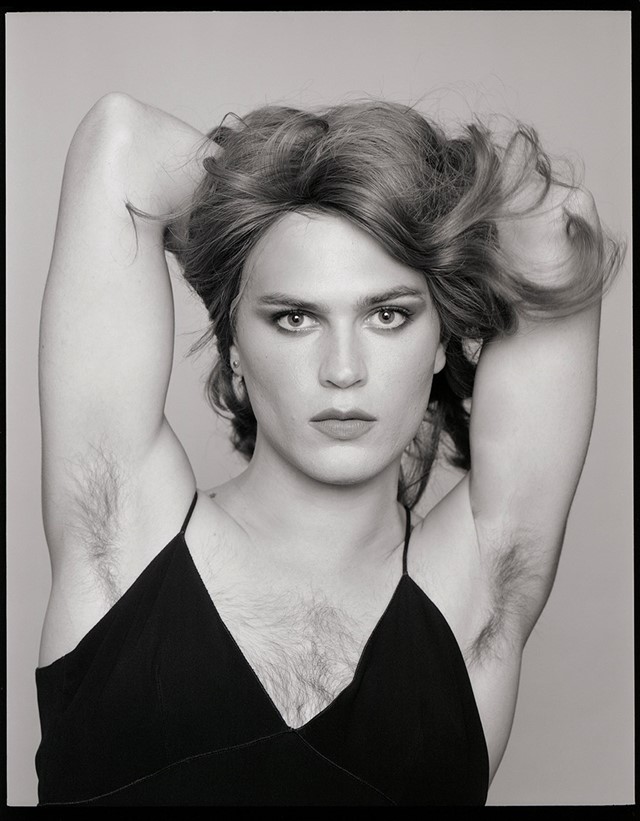

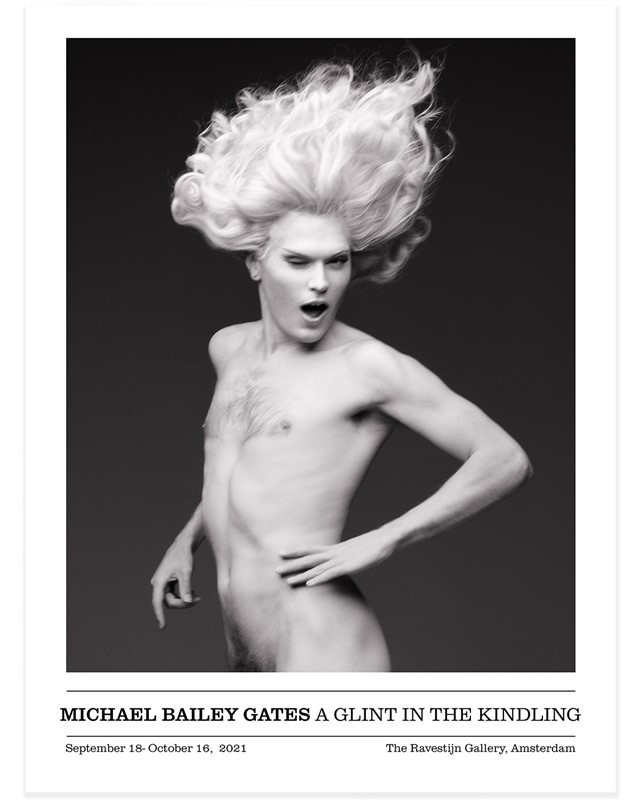

It’s not easy to be two things at once. Grounded but theatrical, nostalgic but hyper-modern, the photography of Michael Bailey-Gates somehow manages just fine. Like a raised eyebrow or a smirk that gives way to a scowl, these are portraits that carry a touch of mischief in one hand and deadpan delivery in the other. Launching this month at Amsterdam’s Ravestijn Gallery, A Glint in the Kindling marks the American artist’s first solo exhibition and monograph. It’s a little surprising for those who have followed their career so far – across countless magazine commissions, campaigns for Valentino and AMI Paris, and collaborations with Eckhaus Latta and the Greer Lankton Archives. Bailey-Gates’ photographs have long seemed suited to gallery walls.

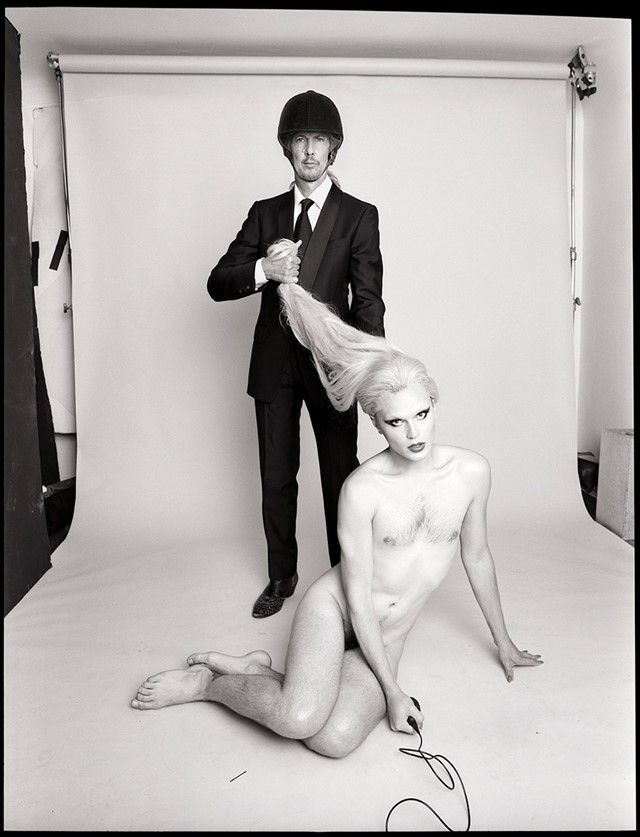

Bound in bright orange, the accompanying book collates 35 examples of the artist’s more intimate work. Models, East Village legends and longtime friends appear in various hats, wigs and states of undress. Now and again, Bailey-Gates will enter the frame too, often clutching the twisting cable of a shutter release. Though meticulously staged, each picture is touched by the brightness of spontaneity – a toothy giggle, a sneer or a smear of eyeshadow.

Having grown up in Rhode Island, a move to New York offered the city’s rich queer history as both photographic and personal inspiration. As a result, Bailey-Gates has set to work crafting a studio world that treats binaries as irrelevant. Jostling with gender in a way that’s simultaneously whimsical and sorely real, the resulting images are never too detached from daily life.

Here Bailey-Gates discusses that sense of whimsy, predicting the future and working with friends.

AnOther Magazine: Your work often makes explicit references to artists like Francesco Scavullo, Jack Mitchell and Greer Lankton. How did you first develop that visual vocabulary?

Michael Bailey-Gates: I think it was moving to New York and falling into the history of the city. Paul Monroe is one of my close friends; he was an artist on that 70s and 80s downtown scene and Greer Lankton’s partner. That whole era has had a huge comeback and we’re fortunate to have so much of it already documented. Some of it was also from working with the artist Kembra Pfahler who I was assisting for a bit. She introduced me to this idea of “availablism”, which is working with what’s around you. Finding other artists who worked in that vein helped to spark that vocabulary for me. If you don’t have a tonne to work with and then suddenly you start thinking that way, it’s a very grateful way of thinking. Your surroundings become a playground for connection. I think that’s what sparked self-portraiture for me too, although I don’t think of my work as self-portraiture at all. But it started at least with the fact that I’m always around, always available to myself.

AM: So much seriousness is often ascribed to gender play, but I think your images also demonstrate the joy of that play, the way that freedom opens you up.

MB-G: My best friend Bobbi Menuez, who’s in a lot of my pictures too, once said in a piece of writing, “People often use the language of grief when talking about my transness.” I thought that really hit the nail on the head. A lot of the time there’s this mourning vocabulary which of course forms a part of it, but it’s not all of it. There’s also so much joy and excitement. It’s such a colourful process. I think we’re here to experience the physical world in a body. So if we’re to be in our bodies, why not have them be ours? There’s a lot of expectations and resistance against that idea, but revolving through the notion of joy has always been a big concept for me, especially when I was in school. At least with my experience, sure there are difficulties that are a significant part of it, but it’s not the whole thing. I guess it’s about holding both, you know?

AM: There’s also a starry quality to a lot of your photos. They have that air of being touched by celebrity.

MB-G: I think having such a love for photography starts to infiltrate your daily life. Like, I just had to say goodbye to my grandmother, and I flew in on a red-eye and went to the hospital and she was so beautiful. And the only thing I could think about was Peter Hujar’s Candy Darling picture, you know? I guess it’s having loved pictures, those references are very personal; they come up in your everyday. They become grounding.

AM: If this isn’t necessarily self-portraiture, does that mean you can detach yourself from feeling vulnerable on camera?

MB-G: No, I think I really abuse myself a lot of the time. [Laughs.]. With my more frequent collaborators, it’s usually people who are excited to be in the picture and that makes a big difference. I do think photography has changed a lot. People don’t need a photographer to come into their communities and document it. Everybody’s a fabulous photographer; we have fantastic equipment, we have amazing cameras. So working with my close group of people and myself feels really authentic to me. Sometimes I don’t know how to function in a social setting if photography isn’t the thing bringing me there. You know, my boyfriend’s a photographer, I went to school for photos, most of my friends are artists or work in photography. It’s brought me everything.

AM: How do you create a mood of confidence on set?

MB-G: I’m glad it reads as confident. I feel like I’m stumbling through it a lot of times. I’m learning to trust my intuition more. I think especially looking at the body of work in the book and the show, there’s always a sense of mischief to it. There’s this sense of doing something wrong that I’ve never really been able to escape. I love that, I’m not bitter about it. On set there’s definitely always an element of play.

AM: There’s a lot of played-out conversations about the way that gender is deconstructed in photography. It's still often framed by whiteness and maleness, stuck in the Tumblr aesthetic of the 2010s. How do you approach that?

MB-G: There’s always the goal of bypassing gender altogether, to be seen beyond an explanation. I think you and I come from a similar place in terms of the Tumblr generation and being young on the internet. I remember taking a gender and sexuality class at college and this teacher was so frustrated with us because we couldn’t see beyond our western perception of Tumblr-fied gender. She explained how in many cultures, these concepts had been around for a long time, whether in public or private. I felt so evolved when I was younger, having had that kind of internet curriculum, but there’s so much we don’t know. There’s so much queer history that’s happened in private. It’s also so specific to every individual. I think constantly pushing against set roles and imagining ways of being beyond the confines of a binary is a comfortable place.

AM: You’ve mentioned that you made these photographs to affirm a coming reality. What does that reality look like?

MB-G: I think pictures have a magical ability to predict the future a lot of the time. When I’m working so intimately with myself or with my friends, I’ve found that sometimes I’ll take a picture and then years later it’ll make more sense. In referencing this idea of a coming future, I really do believe the ability to “hold both” is the way forward. It’s not so black and white. Photography has had a controversial history with portraying the truth and I think, after all those broken promises, the audience now recognises their desire for a change. I think of A Glint in the Kindling as this sparking of a bigger fire. It’s like saying, “This is just the beginning”. I’m not demanding a new perspective, more offering an alternative. It’s such a relief when you start to tap into that way of thinking – to be able to say, it doesn’t have to be one or the other. It can be both, you know?

A Glint in the Kindling is on view at the Ravestijn Gallery until October 16. Bailey-Gates’ monograph is available now.