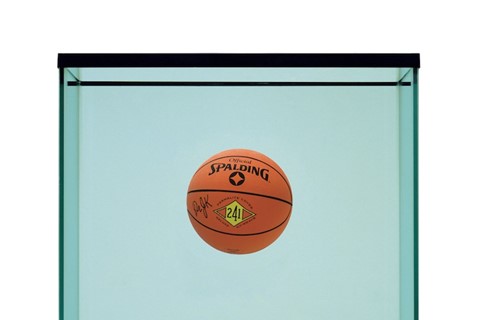

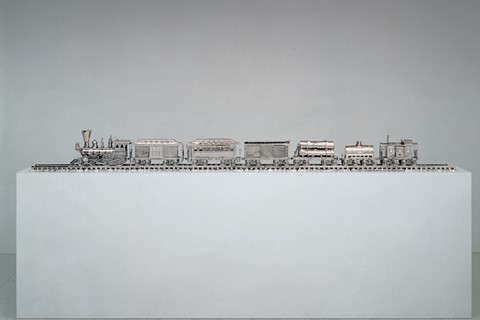

Glossy, flawless and formidable: the reflective surfaces of Jeff Koons’ highly polished sculptures mirror their maker in more ways than one. With their impossibly perfect finish and unashamed opulence, they are fitting monuments to Koons’ own insatiable ambition to stretch the boundaries of his craft. Be it a 10ft steel balloon dog, a pool inflatable in aluminum or a metallic toy rabbit that sold for over $90 million two years ago, Koons relishes the chance to defy judgements on seemingly banal objects, elevating them to something akin to a modern-day totem.

Beyond their cool, hard surfaces and record auction prices is the story of Koons himself. A long-term admirer of Andy Warhol and Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades, he is committed to what he himself terms “a heightened state”, a euphoric sense of affirmation within the viewer. Reflection is an essential element of this search for transcendence and has been for as long as he’s considered himself an artist, with early works like his 1979 Nelson Automatic Cooker/Deep Fryer or his 1986 Luxury and Degradation series offering alternative, judgement-free perspectives on the everyday flotsam of domestic life. In his more recent, meticulously fabricated feats of pristinely buffed steel, reflection has remained central, incorporating the viewer into the work and holding their gaze with a mesmerising sheen.

For Shine, his new, aptly named exhibition at Florence’s 15th century Palazzo Strozzi, Koons has presented a jewellery box of mirrored surfaces in steel, bronze and glass. From the paradoxical inflatables that feign weightlessness yet require to be lifted by crane, to immaculately replicated masterpieces that Koons has used to stage his recent Gazing Ball series, the veteran US artist proves he is still a master of the spectacle.

Finn Blythe: You made your first mirror pieces once you’d moved to New York in the early 1970s. What appealed to you then about working with reflection?

Jeff Koons: Robert Smithson. When I was a younger artist, I had no desire to be in New York or the type of artistic dialogue that I perceived in New York. I liked Pop Art but I wasn’t attracted to Abstract Expressionism so I pursued art that was more of an inward journey, more narrative art. I studied in Chicago with the Imagists, so when I came to New York all of a sudden, I was really moved by Smithson’s work and photo-narrative pieces. I had a desire that my work would be less about the subjective and be more objectively based, that everything would have an equal meaning to me as to someone else. I was attracted to Smithson’s work, to Robert Morris’ work, [Donald] Judd’s work, and so when I made these pieces I was trying to also remove myself, remove my own identity. Sometimes if I would put something in a work, I’d think, “That’s almost too much about my own sexuality or some little clue about myself.” But at a certain point, I experienced really strong sensations from these pieces, so I have this discourse where I still want to continue with really impactful Gestalt-type art, but at the same time I want to believe that it’s objective.

“I loved the metaphysics of the mirror” – Jeff Koons

FB: The mirror crops up repeatedly as a theoretical device not just in art history but philosophy, anthropology, science … In many ways it helped facilitate a sociological transition from the collective to the individual. How conscious were you of its social value and meaning in your early work?

JK: It’s interesting because I believe what you’re saying, it’s probably true, the mirror eliciting this sense of the individual. But then I realise that my intentions are to bring it away from the individual and back to the collective. Usually when people think about mirrors in art they bring up narcissism. To me, I don’t understand it. I understand affirmation, but that’s something completely different. My father was an interior decorator and he owned a furniture store, so I grew up around mirrors, I grew up around objects. In my father’s store, an ashtray would just be there displaying itself, a mirror would just be there displaying itself, so I saw them as objects. But I loved the metaphysics of the mirror. It’s a different time that’s in reflection, it’s close to the here and now but it’s a different time.

FB: There’s that slight delay.

JK: Yeah. And so to have affirmation, not only of the self but of other things in the world, along with this delay, and to feel automatically through this affirmation the excitement for your own potential. You’re here, you’re alive now, so automatically you’re confronting your future. That’s what I enjoy about the experience: a heightened state. It’s like getting two out of three.

FB: Just like that old Duchamp quote about the work being completed by the viewer, these works require a live audience. In a sense that feels like the perfect message of defiance after the 18 months we’ve just had of virtual exhibitions. Your works really come alive once you’re nose to nose with them.

JK: All life is kind of that way. Relationships are that way. And at the end of the day everything is a metaphor for people and interacting with the self, to trust the self. It comes back to self-acceptance and then once somebody does that, the ability to accept other people. That’s objective art, the ability to accept others. So the idea of the viewer finishing the work is something that actually came about through Alois Riegl and Duchamp would have picked it up from him. But Riegl was the first art historian in the late 19th century to speak about the concept of the beholder’s share. The beholder’s share was actually termed by two of his students, Ernst Krist and Ernst Gombrich, and stated that artists can create something but it’s the viewer who finishes the masterpiece. I came into contact with that specific information because of Eric Kandel, the Nobel Prize-winning neuroscientist who devoted his study to memory. He always enjoyed my work and my use of reflection because of its association with the beholder’s share.

FB: Well that’s a good segue to ask you about the relationship between memory and reflection in your work. You mentioned earlier that you refrain from bringing the personal into your work but in many ways your work references personal chapters in your life.

JK: I see reflection as tying to nature, tying to the glistening of light on the water and the sun. As soon as you’re tied to the sun you’re tied to the concept of time and a sense of almost endless time, but then the realisation that everything comes to an end – even the sun. I believe in biological memory, so just as we have intuition about things we have profound biological memory, like how our body has memory for the release of certain chemicals or how to create different organs. We have a memory of feeling and what it means to be a human being, what our history is.

FB: Another fascinating element of your sculpture is their fabrication, which I gather involves years in R&D before anyone attempts making them. I was curious to know how closely you engage with that process?

JK: I generate all the ideas for my work. I’m a very intuitive artist, I focus on my interests very intensely and that’s how I’m able to decide what I want to make. That leads me to the abundance of information within the area I’m interested in and then eventually I’ll take action and I’ll move on making a certain work. I’ll create systems within which that work can be created to the specifications of what the original intentions were. So I’m putting up different control aspects that can protect that, it’s as if I’m making every step of that process myself, that I’m not leaving something up to interpretation. Interpretation is of course beautiful but within the creation of my work it doesn’t have a place, it’s about the system where the intent is for the work to be realised.

FB: So if we take your Gazing Ball series for example, I read that it’s not uncommon for you to go through 350 of these balls before you find ’the one’.

JK: It’s kind of old school [laughs].

FB: It’s old school but it also speaks of an incredible devotion to detail and a flawless finish. Why is that so important to your work?

JK: I don’t want the viewer to be distracted. I want them to stay with the abstraction for as long as possible. But it is a little old school because they’re hand-made, they’re blown glass pieces and with that all the different prospects of having tails within the glass or getting imperfections, little air-bubbles or inclusions, all these things happen.

FB: I love what you say about distracting the viewer because in many ways you’re presenting an illusion, works that defy their physical properties. It only takes one small imperfection for the whole illusions to crack, for it all to come down.

JK: Well it’s to sustain something. I mean everything always comes down, mountains crumble to the sea. But it’s to be able to sustain that communication for as long as possible. I think there have been certain studies that people glance maybe an average of seven seconds at a painting or something close to that range. But it’s to be able for somebody to stay a little longer. I mean, each second you maintain their gaze they’re interacting with themselves.

“I’m trying to become a vaster human being, trying to be a better person, trying to be better in all manners“ – Jeff Koons

FB: Finally I wanted to ask you about showing in this incredible city and palazzo, a place bursting with Renaissance treasures which is of course a period very central to your work. When you showed at Versailles, another location rich in historical context, you had a very clear feeling about which works you wanted to show in which room. How has this experience compared?

JK: Each location is different but it was very intuitive in Versailles. I walked through the Palace and I knew immediately that I wanted Michael Jackson in the Salon de Mars and I wanted the Rabbit in the Salon de l’Abondance and Balloon Dog (Magenta) in the Salon d’Hercule. Here I worked from models and there are certain restrictions that you have in certain places, what you can do and can’t do. But what was important to me is to have an exhibition here in Florence with its tremendous history, to be able to be in dialogue, somewhat, with the history of art, and not just within our contemporary time but to have that connection to the past. And to the limitations that I have, and I’m trying to become a vaster human being, trying to be a better person, trying to be better in all manners, but to my limitations, to try to be as generous and as giving and trying as an artist as I can be.

Jeff Koons Shine is open at Strozzi Palace in Florence until 30 January 2022.