AnOther shares a list of the most influential, women-led photography releases, spanning from 1843 to 1999

It’s a fact: the first photo book was by a woman. Anna Atkins’ exquisite edition about algae antedated, by eight months, The Pencil of Nature (1844-46) by William Henry Fox Talbot, the Englishman who had aspired to produce the first photographically illustrated book. Yet why is Talbot constantly cited as the creator of the first photo book, with the words “commercially available” often added to oust Atkins from the spot (not to mention the tedious technical contestations over whether Atkins’ works are considered photography or merely “photographic prints”)?

While the “who came first?” debate – perhaps a perverse male fixation, anyhow – is indeed tiresome, what’s further troubling is the continued omission of women’s histories from the photography canon. The multi-platform photography organisation 10x10 Photobooks seeks to tackle this underrepresentation head-on with their valuable new anthology, What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999. The latest in their ongoing examination of photo book histories, this travelling reading room traces the period from the birth of photography to the dawn of the 21st century, categorised in thematic chapters in which stalwarts of the medium rub shoulders with lesser-known practitioners. To mark its release, here are some of the most outstanding photo books by women.

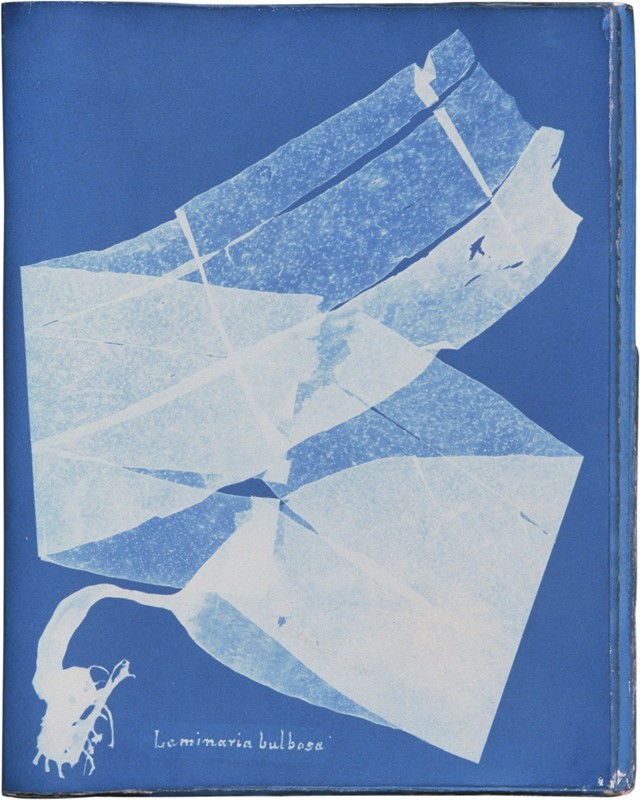

Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, 1843–53, by Anna Atkins

Kicking off the photo book, Victorian botanist and self-taught photographer Anna Atkins’ three-volume masterpiece plunges readers into the cerulean world of cyanotype: a then-nascent photographic process (invented by Atkins’ friend Sir John Herschel) of placing objects onto chemically treated paper and exposing them to sunlight to reveal their silhouetted impressions. In the spirit of science and photography, Atkins endeavoured to catalogue specimens from her huge seaweed collection. These mesmeric, peculiarly postmodern studies of dried algae, fern fronds and flowers – floating against alchemical, and entirely accidental, shades of Prussian blue – prevail for their technical prowess and unfathomable precision. Delicately hand-labelled and hand-stitched together, they serve as modest odes to the bounty of the natural world, monumental but fragile. Once upon a time, Atkins showed us an earth worth discovering. Today, she shows us an earth worth saving.

Carte-de-Visite Albums, 1878–1890s, by Arabella Chapman

With first-person accounts of life lived as a Black person during the post-Civil War era so rare in comparison to the skewed racial narratives propagated by subjugators, these two photographic albums provide precious insights into the private and public worlds of Arabella Chapman, an African American music teacher from Albany, New York. One album presents Chapman’s family, friends and female peers through aspirational studio tintypes that are held in cut-out frames, amounting to a generous snapshot of her middle-class community. The other is more outward-facing in nature, and deepens the narrative. Most likely displayed in Chapman’s home for guests to peruse, it integrates mass-produced carte-de-visite of prominent figures in Black American history, including Abraham Lincoln (signalling Chapman’s political beliefs) as well as Frederick Douglass, the famed abolitionist and advocate of reclaiming “photographic self-representation” as a tool for promoting visibility. Chapman’s self-curated albums, bound in luxurious green leather, carry this same power.

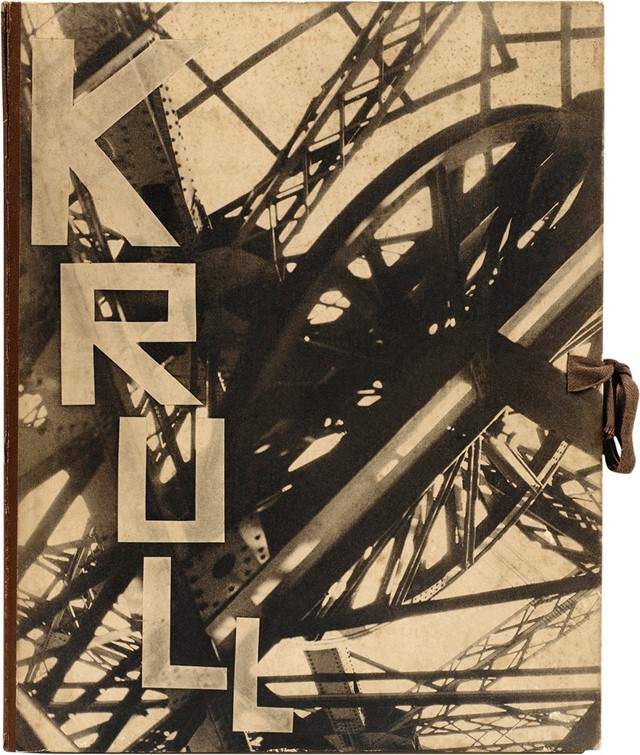

Métal, 1928, by Germaine Krull

Though criminally overshadowed by her male contemporaries, Germaine Krull was not only prominent in European art circles during the 1920s, but a pioneer of the avant-garde photography movement, New Vision. Of her prolific photo book output towards the end of the decade, her most striking is this portfolio featuring 64 plates graced by razor-sharp shots of steel structures: cranes, railways, generators, the Rotterdam transporter bridge and the Eiffel Tower. Shifting in scale, perspective and framing, Krull reproduces the jagged spaces of Futurism and the muscular thrusts of modern engineering. For those who are unfazed by such vertiginous vantage points, Métal delivers in its dynamic associations and kinetic vigour: a modernist triumph by a true maverick, who went on serve Free France with her camera during WW2, before going off to live as a recluse among Tibetan monks.

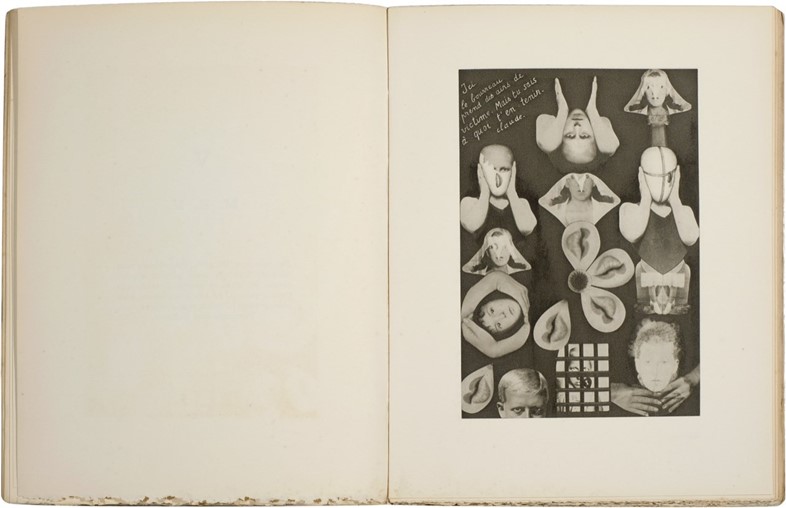

Aveux non avenus, 1930, by Claude Cahun

“Masculine? Feminine?” writes French Surrealist Claude Cahun in Aveux non avenue. “Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.” Such is the defiance of this anti-memoir. Produced in collaboration with Cahun’s lover and stepsister, Marcel Moore, it collects poems, dreams, parables, aphorisms and montaged self-portraits to interrogate the prisms and prisons of identity. Cahun stages the self as a spectacle of distortion, shimmering with psychic obscurities and erotic ambiguities: a force of genius, flaunting the interchangeability of masculine and feminine personae; or a soul in crisis, wandering into limbo, from one mask to another. At odds with the Surrealists’ ideal of woman as muse or femme fatale, this book did not meet success upon its release. But Cahun was ahead of the curve when it came to critiquing conventions around gender, sexuality and femininity, and is today regarded as a precursor to the “epoch-making” Cindy Sherman. Variously translated to Cancelled confessions, Disavowals or Denials, this is a beguiling, refracted mirror of a book that is forever being written, forever new.

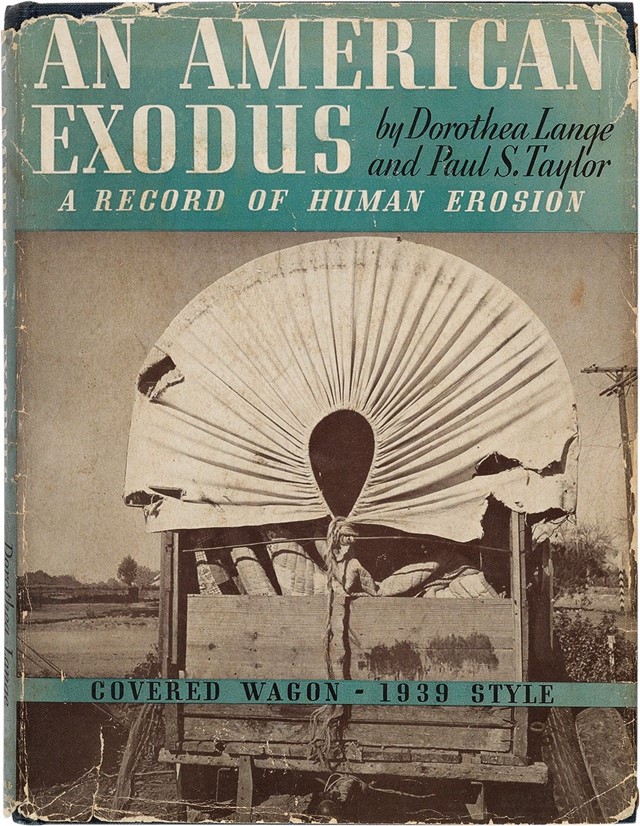

An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion, 1939, by Dorothea Lange and Paul Taylor

Sometimes, photographs not only stop time, but stop us; and few attest to this more profoundly than Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1938). Despite becoming instantly famous following its widespread media reproductions, Lange and her husband, Paul Taylor, decided to exclude it from their book for fear its emblematic, heart-wringing power could distract from what they hoped would be a factual record of the environmental catastrophe of the Dust Bowl and economic and health requirements of displaced farm labourers in the Midwest. Lange’s individualising portraits are enhanced by vernacular quotations that she and Taylor compiled in the field. By way of these then-innovative interventions, they produced a new kind of book: one which granted the space for its subjects to speak. An American Exodus is a supreme work that lodged itself into the cultural fabric of America, and lodged the Depression into the imagination of the world.

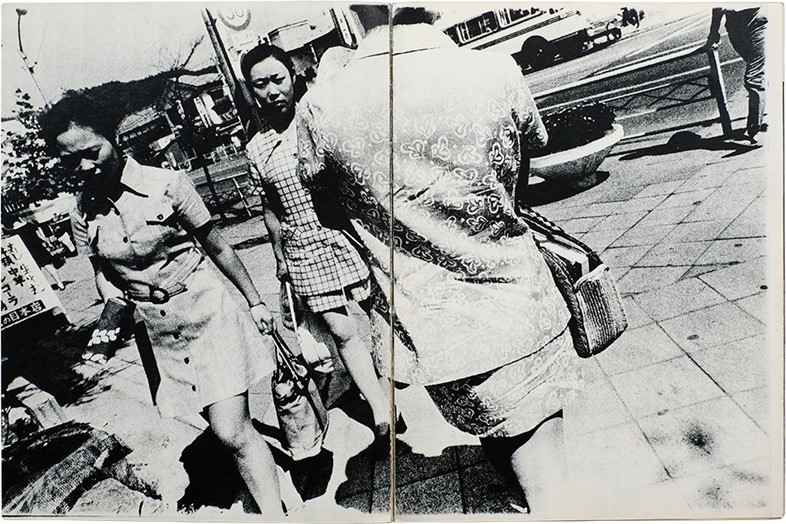

Shikishima, 1971, by Tamiko Nishimura

Those who believe that the Japanese “school” Provoke is a boys’ club can be cheered by the achievement of Tamiko Nishimura’s poised photo-novel Shikishima, which narrates the photographer’s odyssey across Japan. There are strong nods to Daido Moriyama – whom she assisted in the darkroom for a time – via her employment of the are-bure-boke aesthetic, and, in keeping with the spirit of the times, she rejects objective reportage by filtering social commentary through the veil of expressionism. However, we feel Nishimura finding her own voice, too. Diverting from the after-hours bar shots – the mainstay of Provoke’s male protagonists – Nishimura has a keen regard for women, whose kimonos are drenched in the bright lights of the new, consumerist Japan. While the clash between the metropolis as a symbol of preternatural progress and the country as a custodian of conservative values might indeed be the leitmotif of Nishimura’s road trip book, it is also an eloquent account of young woman being liberated by her lens.

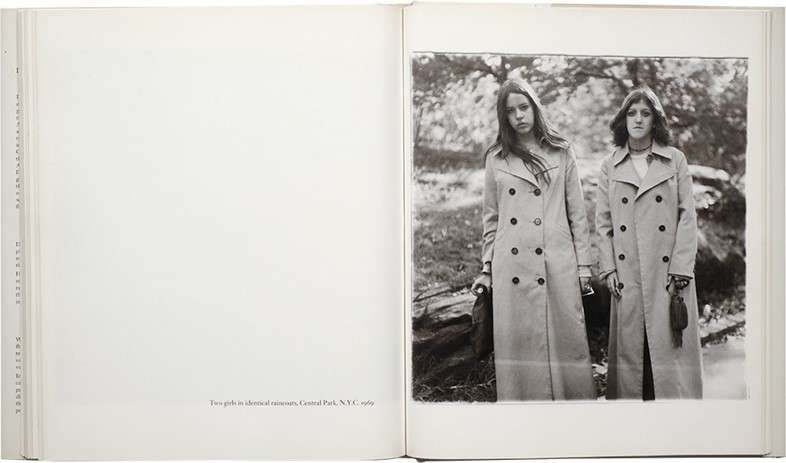

Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph, 1972, by Diane Arbus

Much has been written about Diane Arbus; about her cloistered, privileged childhood; her escape from her status-conscious life into a world peopled by giants, nudist campers, triplets, grand dames, circus folk and recluses. But her work is, undeniably, as iconic as it gets in any medium. The potency of this monograph, published one year after Arbus’ suicide, resides in its narrowness between photographer and photographed, plumbing the depths of Arbus’ psyche as much as America’s. There’s no doubt witnessing Arbus’ collaborations with her subjects – with whom she connected spiritually, sexually and artistically – can feel exploitative. When on view at MoMA in 1965, Arbus’ photographs had to be wiped of spectators’ spit each morning. For many, they bore the taint of sin; secrets of secrets that should have remained closeted. Yet railing against the cruel nature of an uncaring society, Arbus believed that her subjects – their disconcerting stares, their saintly auras – were worth photographing. At its best, this book lends credence to that famous formulation by John Berger: in seeing the world, we are also seen by it.

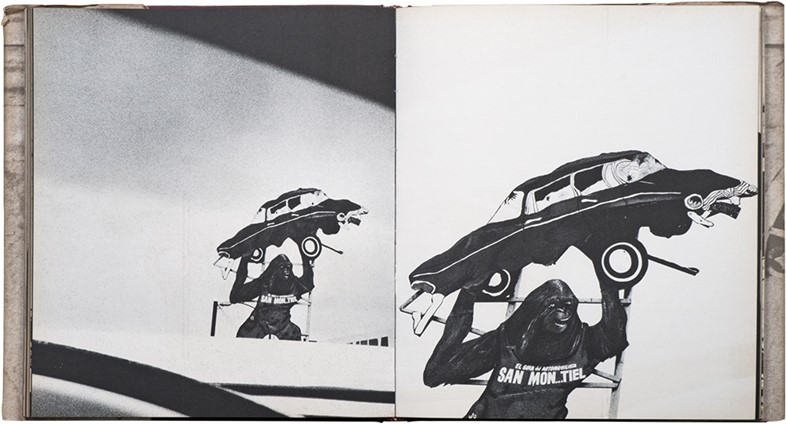

Sistema Nervioso, 1975, by Barbara Brändli, Román Chalbaud and John Lange

The result of a lively collaboration between photographer Barbara Brändli, playwright Román Chalbaud and artistic director John Lange, Systema Nervioso is a stunning example of the possibilities when image, text and design synergise. Although never named, the book takes as its subject Venezuela’s capital, Caracas (here, “the valley”), when the country was experiencing an oil bonanza. With an eye for the graphic – or calligraphic – Brändli’s photogravures certainly deliver, revealing a city dense with signage, graffiti, billboards, mannequins and objects of devotion. Gritty visions are offset by the boldly coloured papers on which Chalbaud’s poetic captions sit, yet this is no mere pop manifesto. As its title suggests, it seeks to enter the “nervous system” of Caracas’ civilians, entangled in the contradictions of urban, Indigenous and colonial cultures: a little-known Latin American title that insists on leaving its mark, not least for the slight black residue that lingers on readers’ fingertips. Perfection.

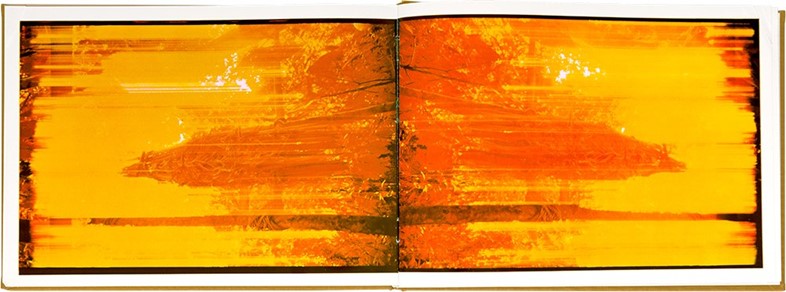

Amazônia, 1978, by Claudia Andujar

Claudia Andujar’s 1971 encounter with the Amazon’s Yanomami people – threatened by disease, deforestation, invasion and exploitation – initiated an activist impulse as much as an artistic one. Immersing herself within their shamanic culture, Andujar experimented with infrared, multiple exposure, slow shutter-speed and Vaseline-smeared lenses, creating entirely authentic images that eschew ethnographic photography in the traditional sense. Cinematically orchestrated across double-page spreads, these dazzling visuals approximate the Yanomami’s cosmological worldview: specifically, towards Amazônia’s euphoric end, the trips achieved through ingesting the hallucinogenic snuff yãkõana, believed to facilitate dialogue with forest spirits. Andujar later departed from her career as an artist to dedicate herself to campaigning for the protection of Yanomami lands, which, in June 2021, were recognised by Brazilian authorities (despite the president’s continued backing of Amazon-destroying activities for profits). In light of this, Andujar’s ongoing contribution to this people’s visibility should be considered one of great salience.

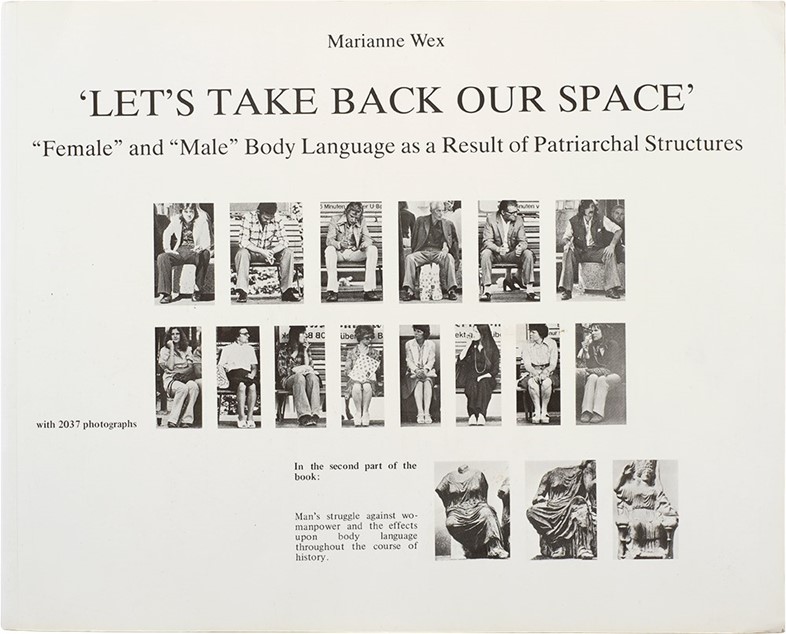

Let’s Take Back our Space: “Female” and “Male” Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures, 1979, by Marianne Wex

Celebrated upon its publication but largely forgotten in the following decades, Let’s Take Back our Space, by German conceptualist Marianne Wex, has only recently cemented its status as a landmark work in feminist history. The vast taxonomy – composed of thousands of Wex’s surveillance-style photographs and images culled from magazines, advertisements and television – scrutinises the socially replicated nature of kinesics. Meticulously categorised by gender, posture and body part – with men hierarchically arranged above women – the studies repeatedly evince women’s contracted poses, with men more entitled and obtrusive. While Wex also hops between epochs, dedicating one section to the search of the “manspread” in ancient statues, this work never feels totalising thanks to the inclusion of anomalies. Engrossing and always edifying in her advancement of the feminist recuperation of public space, Wex enables us to read ourselves in these images and, in turn, emancipate ourselves from their antiquated codes.

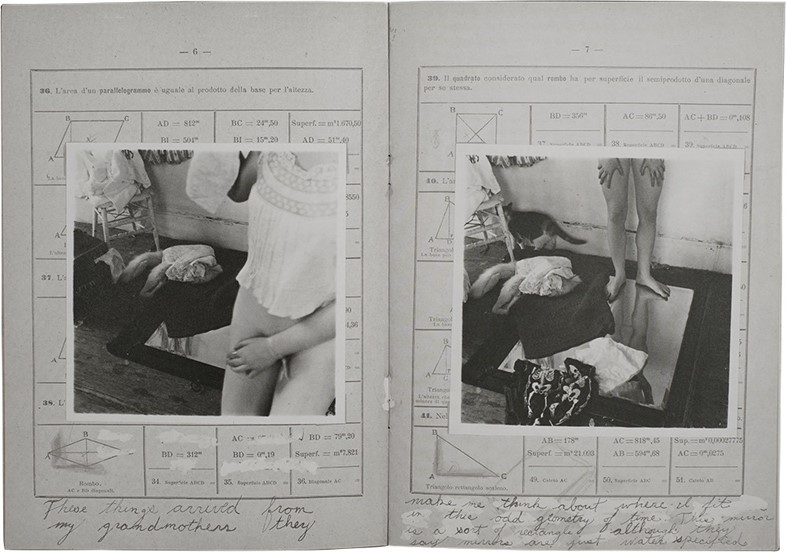

Some Disordered Interior Geometries, 1981, by Francesca Woodman

There is something hard to grasp about the lifetime of Francesca Woodman, and her only self-published is equally enigmatic. Affixed to the pages of an Italian maths book are 16 gelatin silver prints picturing Woodman surrounded by objects: an antique mirror, rabbit ears and her recently deceased grandmother’s clothes. “They make me think about where I fit in this odd geometry of time,” orbit the pencilled thoughts of Woodman, for whom the square frame was not only a space her body could inhabit, but an allegory for the self and its meanderings through planes. There are echoes of the surreal worlds imagined by Lewis Caroll and Claude Cahun here, but the tenor is more overtly macabre. In one frame, Woodman hides her face, as if to vanish into the white of the background. Some Disordered Interior Geometries was published days before Woodman’s suicide at the age of 22. Copies were distributed at her funeral; a swan song of sorts, frail but immovable.

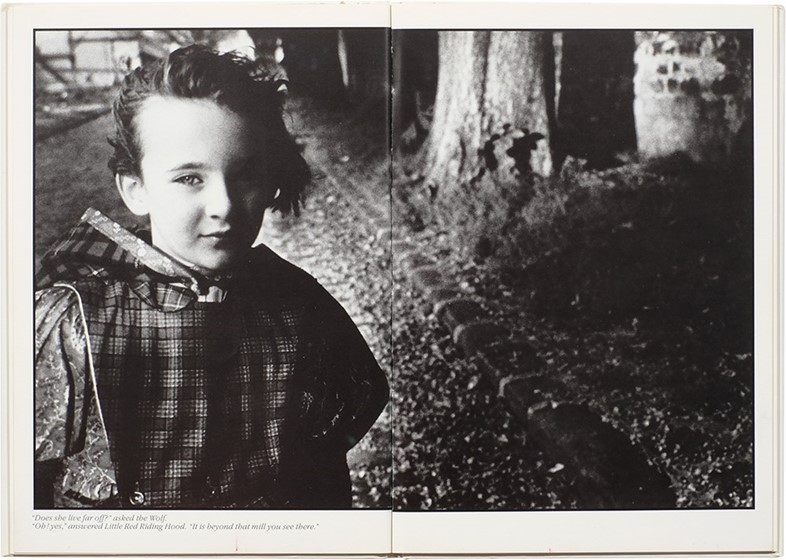

Little Red Riding Hood, 1983, by Sarah Moon

Charles Perrault’s supposedly “innocent” fairy tale, Little Red Riding Hood (1697), is actually as sinister as they come, namely for making its protagonist, “the prettiest creature who was ever seen,” at fault; a provocateur for the evil Wolf’s attention. Sarah Moon’s remarkably dark retelling in this picture-book-cum-crime-thriller thus feels utterly fitting. Though the text is faithful to Perrault’s, Little Red Riding Hood is portrayed as a street urchin, trudging to Grandmother’s through winding, cobbled streets, while the Wolf stalks her in a black, predatory animal of a car. Upon winning a children’s book award in 1984, the adaptation sparked scandal and even met censure. Moon’s rendition of the famous encounter scene is undoubtedly chilling, placing readers in the position of the driver-Wolf who blinds the heroine with headlight eyes. Yet this is a dauntless reckoning with the sexuality and violence inherent within Perrault’s cautionary tale; one which effectively uses photography to engage our sense of reality while imaginatively transposing the dangers of the forests into today’s city streets.

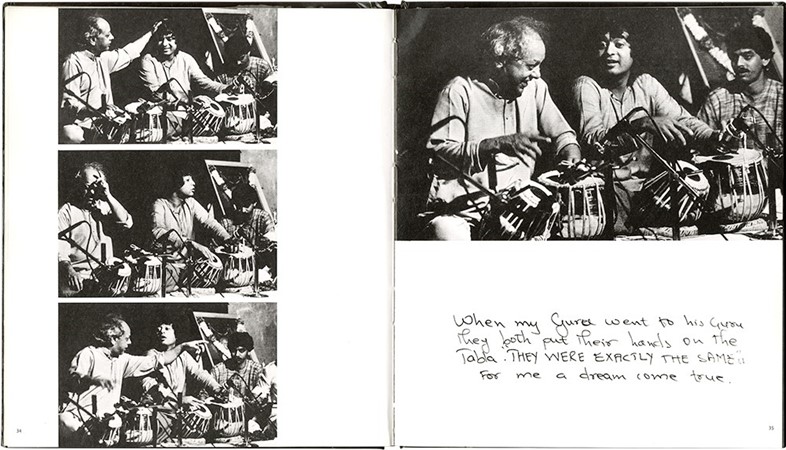

Zakir Hussain: A Photo Essay, 1986, by Dayanita Singh

Perhaps no one has pushed the photo book to its expansive limits more dedicatedly than Dayanita Singh, and her treatment of photography as object, archive and memento can be traced back to her first work. When Singh was 18, she met the Indian tabla virtuoso Zakir Hussain at a concert. Hussain invited Singh to photograph him, and she did, over six winters. The photographs culminated in this prismatic portrait of Singh’s protagonist: there’s Hussain the performer – rapturous, majestic – and also Hussain the father, husband and son. Alongside the imagery, Singh scribbles down musings, measurements and calendars. The deft, often surprising intercourse between these elements serves as a subtle showcasing of Singh’s intuitive understanding of narrative as well as lyricism. Adjacent to a photograph portraying Hussain’s wristwatch, plasters and medicine dance Plato’s words: “Music and rhythm find their way into the secret places of the soul.” And into this book, too.

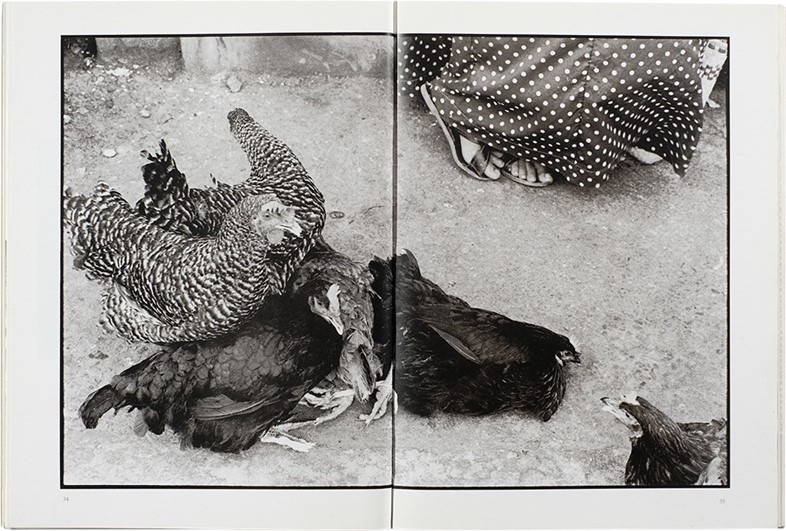

Juchitán de las mujeres, 1989, by Graciela Iturbide

The long-established matriarchies of Juchitán, Mexico have acquired a mythical status, in turn making them a subject of fascination for photographers: Paul Strand, Edward Weston et al. Though Graciela Iturbide extends this lineage with her documentary book, the gravitas with which she portrays the women – of whom included are the highly-revered third-gender muxes – is distinct. Proximity is palpable in these photographs, which picture women attending funerals, bathing, breastfeeding and worshipping Huehuecóyotl, the god of music, dance and mischief. They radiate an ethereal self-possession, wear their sexuality on their sleeves and embrace economic independence (the men leave at dawn to hunt iguanas while the women go to the market to sell them). It is through the irony that such progressive traditions are the products of Juchitán’s systematic exclusion from modernisation that Iturbide’s book becomes not so much about timelessness as about fate.

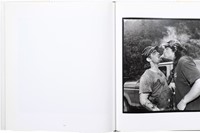

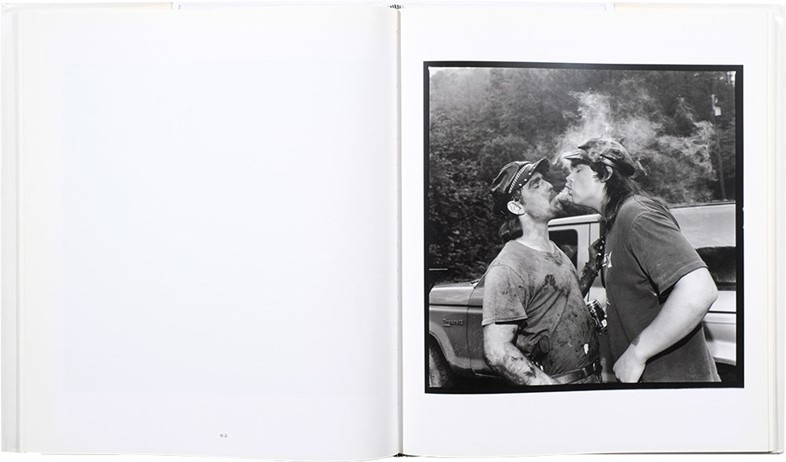

Grapevine, 1994, by Susan Lipper

While Susan Lipper’s gothic saga owes much to the methodologies of Doris Ullman and Walker Evans – who embedded themselves among Appalachian craftspeople and sharecroppers, respectively – it is radical for its truth-questioning. In 1988, Lipper discovered Grapevine Hollow – a town so small it doesn’t appear on the map – and was, in effect, adopted. Rather than rehearsing old narratives around “poor rednecks”, Lipper involved her mostly male subjects in their own myth-making. Though imbued with integrity and intense collaborative values, the 55 photographs – framed like quotations – don’t shy away from stereotypes seized upon by the media: violence, family feuds and lifestyles of decay. Have the residents caricatured themselves? As for the sublime display of a man blowing smoke into another’s – tenderly like a kiss – the homoerotic edge is strong. However, readings of Lipper’s scenarios are entirely speculative, as if heard through the grapevine.

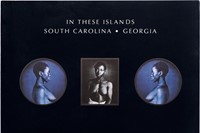

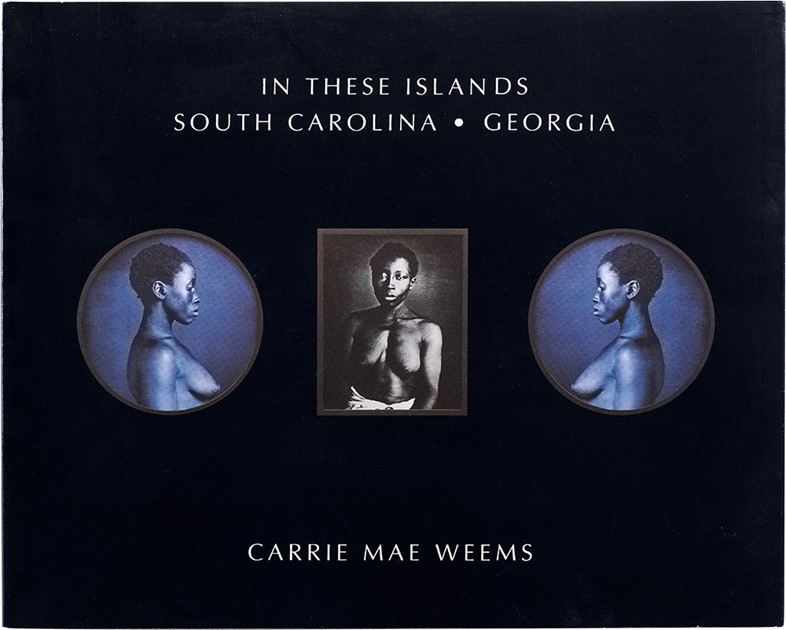

In These Islands: South Carolina–Georgia, 1995, by Carrie Mae Weems

“Went Looking for Africa: found it echoing in the voice of the Geechee’s Gullah,” writes Carrie Mae Weems in this charged book, announcing her symbolic homecoming among the Black Gullah community which, because of their isolation on islands off the coast of Georgia and South Carolina, has retained strong elements of West African culture. Assuming a fascinating omniscient perspective, Weems wanders through an atmospheric world, uncovering its sights and sounds while never turning away from the death that lies within too. Haunted graveyards, praise houses and ceramics are combined with prose in sequences that obscure the points where Gullah myths end and Weems’ voice begins. The only faces here are those of the enslaved father and daughter pictured in Joseph T. Zealy’s 1850s daguerreotypes which are appropriated on the front and back covers. Here, Weems conceives a place that is inseparable from African history, lore and the legacies of slavery. The landscape as story, the story as landscape and the drama of race.

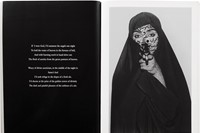

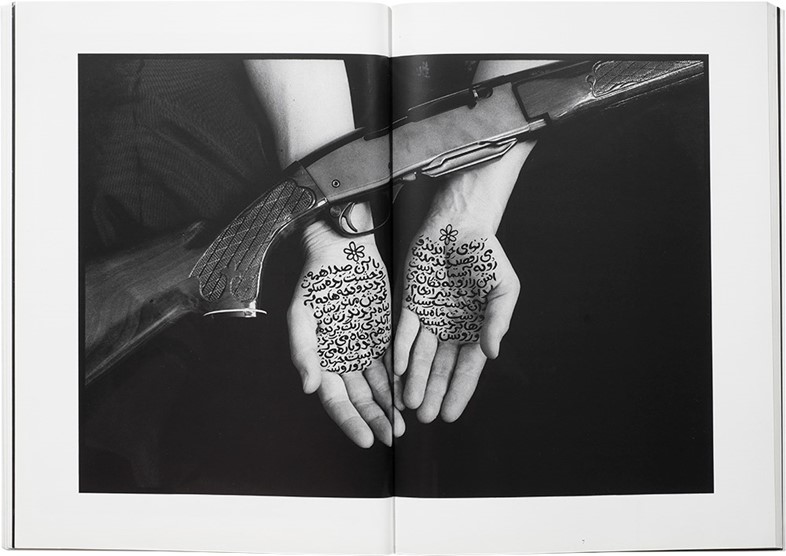

Women of Allah, 1997, by Shirin Neshat

Representing the inception of Shirin Neshat’s extensive explorations of Muslim womanhood through art, these startling photographs were created upon the artist’s return to Iran after her exile during and following the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Addressing the new regime’s supposed empowerment of women through a call to arms, Neshat stages chador-clad women holding, hiding or harnessing guns that are both decorative and dangerous. Inscribed on their bodies, like a second skin of flesh, are lines of Farsi verse by feminist poets, giving rise to a complex play between the female voice and the silence of photography. While the themes of oppression and rebellion in these portraits have been well-mined, their more philosophical inquiries probe love, motherhood, veiled sexuality and hands. One significant result of the Revolution was the reinstating of the chador, but with the exception that hands could be exposed. The graceful choreography of hands is a highlight here, underscored by the image invoked in Tahereh Saffarzadeh’s poem in which she offers to participate in the Revolution: “O you martyr / hold my hands / with your hands / cut from earthly means.”

Hiromix, 1998, by Hiromix

As far as breakthroughs go, Hiromix’s was of the most emphatic kind. An ex-student and model of Nobuyoshi Araki, she was influenced by what her mentor dubbed the “I Novel”. Following her first diary-slash-photo book, Girls Blue (1996), Hiromix became the harbinger of a new school of Japanese female photographers (known as onna no ko shashin) who took to Tokyo’s streets with every conceivable type of camera. Her freewheeling, eponymously titled 1998 monograph chronicles the life of a Japanese teenage girl from the inside, weaving fleeting snapshots of cityscapes, shopping malls, fast food, friends and pets with intimate, often nude self-portraits. Though her firm foregrounding of female pleasure is not short of tropes of “girliness” – long applauded in Japanese culture high and low – Hiromix marked a mighty shift in the highly-patriarchal landscape of Japanese photography: one in which women were encouraged to become tellers of their own tales, in their own rights.

What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999, published by 10x10 Photobooks, is out now.