With the advent of the 24/7 media cycle, the art of journalism has all but disappeared. With slashed budgets, few can afford to engage in the glorious reportage of yesteryear, when reporters would disappear into a story for months only to reemerge with masterfully crafted tales of historic import.

Wes Anderson offers a love letter to this kind of journalism with his new film The French Dispatch, which was released last week in the UK. Set in the outposts of an American magazine in the fictional 20th-century French city of Ennui-sur-Blasé, The French Dispatch brings together a star-studded ensemble cast that includes Timothée Chalamet, Bill Murray, Jeffrey Wright, Lyna Khoudri, and Anjelica Houston.

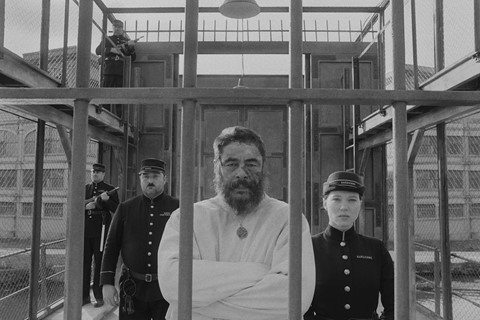

Organised like an anthology, The French Dispatch presents three stories including “The Concrete Masterpiece,” which was inspired by The Days of Duveen, a six-part New Yorker feature on British art dealer Lord Duveen published in 1951. In the film, staff writer J.K.L. Berensen (Tilda Swinton) chronicles the story of incarcerated artist Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio del Toro), who draws inspiration for his glorious abstractions from prison guard Simone (Léa Seydoux) and soon comes to the attention of ruthless art dealer Julien Cadazio (Adrian Brody). But perhaps the true star of this story is the paintings themselves; the magnificent masterpieces that we imagine Rosenthaler creating from inside the confines of his prison cell. In turns bold and brutish, then thoughtful and tender, the paintings explode on the screen, offering a wildly expressionistic counterpoint to the precise formalism of Anderson’s aesthetic sensibilities.

Created by German-New Zealand artist Sandro Kopp, the abstractions present a point of departure for the figurative painter who has received acclaim for his Skype portraits, his hypnotic paintings of the human eye, and his mesmerising portraits of partner Tilda Swinton. Realising “The Concrete Masterpiece” has proven a blessing for Kopp, who continues to draw inspiration from Rosenthaler’s art.

An exhibition of all the Rosenthaler paintings in the film is currently on view at 180 The Strand in London. And in February 2022, an exhibition of early tests and subsequent studies for “Simone Naked, Cell Block J” – the small painting that is the catalyst for the entire plot – will be on view at Ebensperger in Berlin. Here, Kopp recounts his role in The French Dispatch, offering a fascinating look into the creative process.

Miss Rosen: Could you speak about working with Wes Anderson, and the relationship established between film director and painter?

Sandro Kopp: Wes and I have been friends for years and he has been familiar with my work for a long time, so I guess he must have known what he was doing when he asked me to take on this project, though I was quite surprised and very honoured. Wes directed me with kindness and precision, mainly via countless emails during the testing phase. Once we had established the general look and feel of one of the paintings, he was relatively hands-off and left the majority of compositions and the sequence of the paintings up to me.

It was wonderful working with Wes. Collaboration is a comfortable place for me. Having someone else put something in the mix is very helpful and inspiring, especially for someone who is not only a friend but also a genius, and I don’t use that word lightly. I think his work has a formality and a dazzling visual impact combined with a lightness of touch that masks the fact that it’s actually about very deep stuff and universal truths.

MR: How did the story of “The Concrete Masterpiece” resonate with you as an artist?

SK: Primarily, I find it very moving. I can’t even fully put it into words, but every time I see it, it touches this deep chord of what it means to be a creative person. There is nothing cynical in any of the characters. Foundlings, eccentrics, murderers or art collectors – all are living the life they have to and all of them somehow deeply believe that art is truly meaningful.

I think it’s really a story about longing. There’s this moment that happens really frequently in all my work where you get this little glimpse of possibility, but the reality of making that ideal – whether it’s a painting, sculpture, or a book – feels like it always falls short. You realise there’s absolutely no way you’re going to reach it, but we try our best. It’s still pretty good, because it aspires towards the highest ideal. Having a goal doesn’t mean reaching it, it just gives you a clear direction to walk. And of course, the script is written with such razor-sharp wit. There are many lines that I want to put in a frame on the wall or better still somehow hug and cherish.

“In my opinion, a masterpiece is a piece of work that opens a door to mystery” – Sandro Kopp

MR: What are some of the key qualities of a masterpiece, and how has this understanding shaped your approach to creating the art of Moses Rosenthaler?

SK: In my opinion, a masterpiece is a piece of work that opens a door to mystery. Something that affects you in ways entirely beyond words. I like this Wittgenstein quote: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” And I feel it somehow applies to making art: if something can only be reached by painting, then that’s the way it needs to be done. It’s not even to do with expression. It’s just about giving form to something meaningful that could not exist otherwise.

MR: How did you draw upon the work of Francis Bacon, Willem De Kooning, Jenny Saville, Frank Auerbach, and Anselm Kiefer for these paintings?

SK: All of these were just inspiration for the vibe of the paintings: a powerful, visceral, almost violently sensual relationship with the paint. We were very clear that we wanted the artworks to stand on their own and not look too much like any existing painter’s work. They needed to feel like something idiosyncratic that would not look too out of place in a contemporary art museum.

MR: What was it like working in the derelict factory turned on-set studio?

SK: The felt factory was freezing cold, dusty and incredibly loud, as sets were being constructed all around. But it was also a wonderfully open space that I knew I could let loose in. The noise levels meant I always had my headphones on when I was painting in order to maintain concentration. The primary soundtrack for the Rosenthalers are the two last albums by Screaming Females.

In my usual studio practice, I generally work alone and here I had two assistants – Sian Smith and Edith Baudrand, who are both great artists – as well as the muscle and resources of a production crew. The challenge was to stay focused and not get bogged down in arranging all the technical elements: from waiting for the taxidermied beagle to be released from customs so that we could begin young Rosenthaler’s train-car painting, to arranging the re-manufacturing of nine of the panels when we realised that the paint was too heavy to stay on the surface and was cracking off.

MR: Could you share some of the memorable behind-the-scenes moments working on the film that one might never otherwise know?

SK: I did actually physically embody Rosenthaler: I hand-doubled Tony Revolori for all the scenes where we see young Moses painting. My arm was shaved and made up to match his skin tone and then splattered with paint. I then sat close behind him out of the way of the camera with my arm going through his sleeve from a hole at the shoulder.

I also have a cameo as one of the splatter school artists. When we were about to start to finally film the big paintings there was an unexpected 20-minute lull while we waited for a camera arm to be fixed. Given that it was a quiet moment I asked Wes what he thought of the final adjustments I had made the night before to one of the panels. He said he would prefer a particular area in the painting to be a little more structurally fragmented, so I ran for my palette and was up a ladder painting in full costume right up until the minute the machine was fixed and we could roll the camera. In that first big wide shot, panel number seven is still wet.

“Having only three months to develop and paint something that was supposed to look like a genius had worked on it for three years was pretty heady”

MR: Could you describe the relationship between the artworks you made for the film and Wes Anderson’s distinctive approach to cinematography?

SK: The main way in which that relationship exists is perhaps by trying to make the abstract artworks quite distinct from the general rhythm of Wes’s visual territory. These chaotic blasts of colour and dripping, cracking, fleshy paint are pretty much the opposite of the highly organised formality that is considered the Wes Anderson style. It was a gigantic stroke of good fortune that the paintings he asked me to make for the film were exactly the paintings I needed to make for myself.

I tend to have a variety of different bodies of work going at the same time and one always begets another, often in terms of a counter-reaction. The paintings in the film all started with the figure, but there’s a wide gulf between what we would call reality and what’s depicted. It’s much more about how they feel, and the direct line between instinct for movement, colour, and texture. The last series I did before making the paintings in the film were the eye paintings – these tiny wee things – so the opportunity to physically throw my entire at the painting, especially in the early stages, has since then informed everything I’ve done. I’ve just taken that, run with it, and made it my own thing.

MR: What were the most challenging and rewarding aspects of creating the art of Moses Rosenthaler?

SK: The pressure of having only three months to develop and paint something that was supposed to look like a genius had worked on it for three years was a pretty heady challenge. But perhaps the most challenging aspect was that I felt I could do better with “Simone Naked, Cell Block J.” I had made nine versions for Wes and we were getting close to having one that would be right, when suddenly the schedule changed and they started filming the version of that painting that Wes was very happy with, but that I still considered unfinished.

When he showed me the finished film, I knew I loved the big ten, but I felt like I could improve that “Simone”, so Wes told me that if I could make something better, he would insert it into the film digitally. I spent the next year painting dozens of new versions of that same painting over and over. In the end he never did change it and I simply changed my perspective on the painting that is in the film. I found a different visual key to unlock it with and now I’m proud and happy with it. The dozens of other Simones will be the basis of an exhibition at my gallery, Ebensperger, in Berlin early next year.

As for the most rewarding moment ... perhaps it was watching them filming the final shot of the paintings in the Clampette Collection museum. It felt like my babies had come home.

The French Dispatch Exhibition is on view at 180 The Strand in London, until November 14. An exhibition of early tests and studies for “Simone Naked, Cell Block J” will be open at Ebensperger in Berlin in February 2022.

The French Dispatch is in cinemas now.