A key figure in the fertile cultural scene of post-war Tokyo, the photographer helped free the medium from its insular past

It wouldn’t be a stretch to call Eikoh Hosoe a photographer’s photographer. A pioneer of expressionistic post-war Japanese photography, co-founder of the photographic cooperative Vivo, curator introducing works of western master photographers to Japan, and teacher informing the careers of Daido Moriyama et al, he influenced the medium immeasurably. Yet what is most remarkable about Hosoe’s oeuvre – now charted in a magnificent MACK-published survey – is the way it transcends conventional photographic practices. Collaborating with writers, dancers and artists, Hosoe established an infrastructure that encouraged the recognition of photography as a vital artistic force within the country’s avant-garde arts movement.

Hosoe’s interest in the collaborative nature of photography can be traced back to 1959, when he witnessed experimental dancer Tatsumi Hijikata’s adaptation of Yukio Mishima’s homoerotic novel Forbidden Colours (1951), which involved simulated sex with a chicken. The succès de scandale is considered the birth of ankoku butoh (dance of utter darkness), a type of Japanese dance theatre that threw off the rigid constraints of the past. “I had never seen such ferocious dancing,” Hosoe recalled. “Amid the thunderous applause that continued even after the curtain came down, I leapt out of my seat and ran to the green room backstage, my voice quaking from the excitement of witnessing the emergence of such a tremendous dancer.”

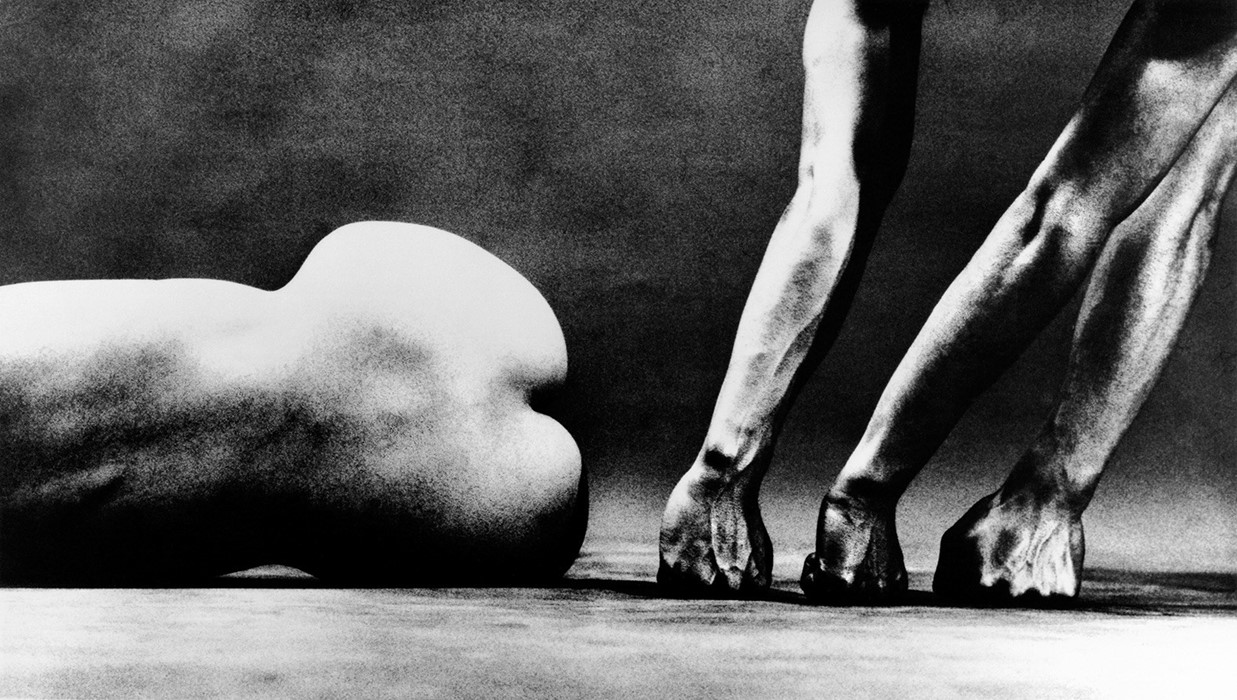

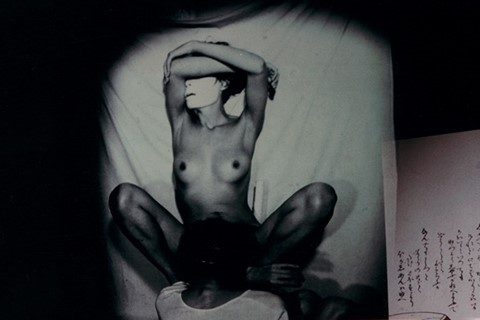

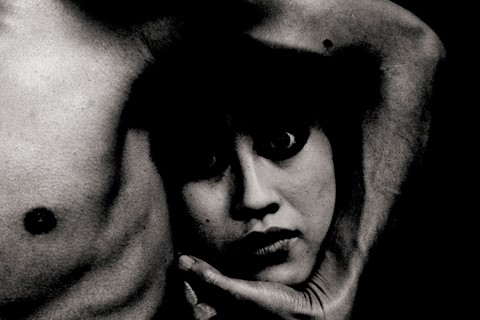

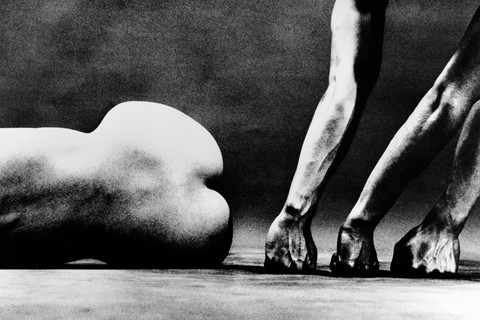

It was an encounter that changed not only the people Hosoe photographed, but his relationship with photography itself. No mere observer, he saw himself as involved in the shutter snap’s creation of a distinct place and time. Hosoe began photographing Hijikata and his ensemble in a different kind of darkness to that of the stage: the darkness of what Hosoe called his “photographic theatre”. The resulting photo book, Man and Woman (1959) – characterised by Hosoe’s exacting sense of form – records an increasingly abstract “dance”. Hijikata’s finely-honed figure appears alongside women who bear symbols of fertility: fish, flowers and so on. Yasufumi Nakamori, the editor of Hosoe’s new publication, contextualises this work in lofty terms: “Hosoe was the first photographic artist to recognise the technique of using an abundance of sexual imagery without aiming to arouse erotic feelings in the viewer, or, rather, even aiming for the opposite effect.”

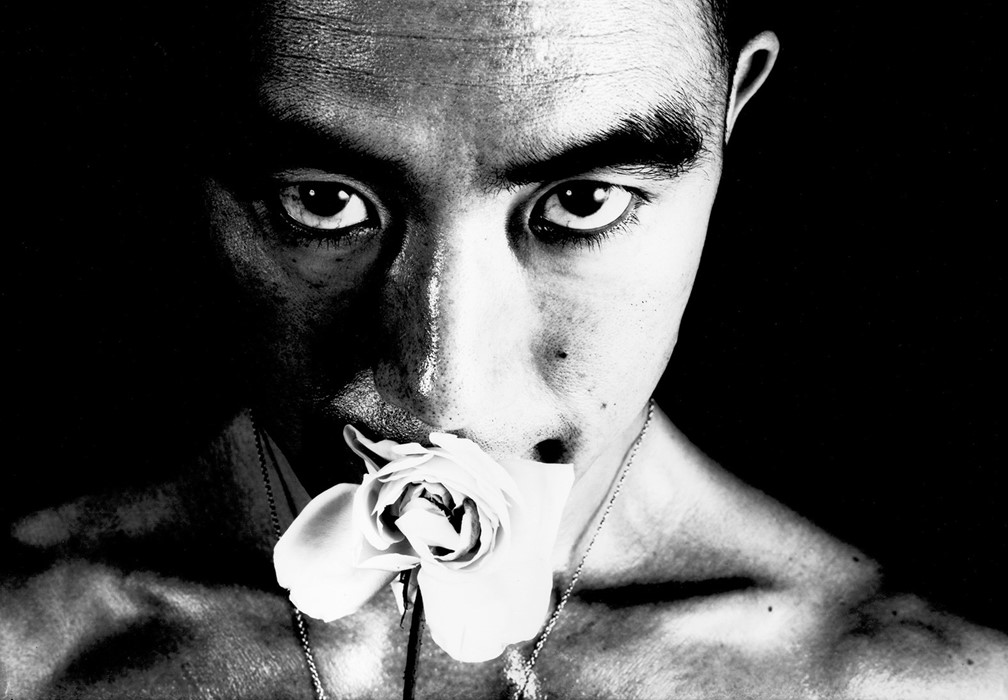

Hosoe’s bold vision caught the attention of Mishima, who invited him to his house to take a publicity portrait. Allowing Hosoe complete directorial freedom, Mishima found himself in a series of sadistic, baroque-inflected tableaux: the signature shot shows him pinned on a mosaic zodiac and wrapped up in a garden hose. Mishima was bewitched, to say the least: “The world into which I was ushered by the wizardry of his lens was alien, contorted, derisive, grotesque, barbaric and dissipated, and yet it was also a realm in which the murmurs of a pure undercurrent of lyricism flowed through some unseen conduit.”

One year after Mishima committed seppuku (the Samurai’s ritual suicide), these portraits were compiled in Ordeal by Roses (1971), a memorial that added to the iconography of Mishima and is today regarded as one of the most complex photo books ever made. Revolutionary graphic designer Tadanori Yokoo elevates Hosoe’s photographs through psychedelic montages which combine Pop Art and ukiyo-e. Bound in black velvet, it nestles in a case that folds out to reveal Mishima floating beneath Hindu reincarnation imagery with roses sprouting from his glistening torso: an ultimate union between the dream of death and the fabric of flesh.

Guts and ghosts are recurring motifs throughout Hosoe’s work. When Tokyo was firebombed in 1944, he was evacuated to his mother’s natal home in a small village in the northeast, where farmers fearfully recited the legend of Kamaitachi: a demonic weasel who haunts the paddy fields and slashes his victims with blades. For Hosoe’s 11-year-old imagination, the imagery was inseparable from the catastrophic events that led him there. “I was afraid that this rural region from my memories would be totally transformed, becoming nothing but a flat and faceless terrain … a victim of modernisation.”

Hosoe returned to the village in 1965 with Hijikata, who also grew up in the region. The Kamaitachi myth provided a language with which they could touch the trauma of the past with child-like sensibilities. So began their retelling-slash-improvisational dance drama. In bleached, cinematic frames, the demon-playing Hijikata seduces women and steals children, like the Pied Piper. Upon its publication, Kamaitachi (1969) offended orthodox photographers, overthrowing traditional notions of what could possibly be rendered by the lens. But, for Hosoe, this was what he aspired for. “The camera is generally assumed to be unable to depict that which is not visible to the eye, and yet the photographer who wields it well can depict what lies unseen in his memory.”

Throughout Kamaitachi, an ever-lowering black line of cloud descends on the landscape like a shroud. Hosoe’s theatrical masterwork is all the more chilling for the way it simultaneously revisits American firebombing and ushers in the nuclear age.

Eikoh Hosoe, edited by Yasufumi Nakamori, is published by MACK and out now.