“The brutal reality is that women’s stories are made marketable – and some are more marketable than others,” Tate Modern curator Emma Lewis tells AnOther as she publishes her sprawling new book, Photography – A Feminist History

When Emma Lewis first discovered the work of artist and activist Joan E Biren (known as JEB) in 2016, she describes it as a “lightbulb moment.” Biren – who began documenting the lives of LGBTQ+ people in the 1970s, and used her camera as a revolutionary tool to advance social justice for lesbians – was well known in the States. So why had Lewis, a curator at Tate Modern, never heard of her?

“[It] brought home to me just how narrow the scope of so-called ‘feminist’ art is within museum collections – and indeed, in my own ‘feminist’ art history education,” says Lewis. “How even the ‘feminist’ histories of art are told with a focus on a very narrow demographic of women; women who associated themselves explicitly with a certain type of feminism.”

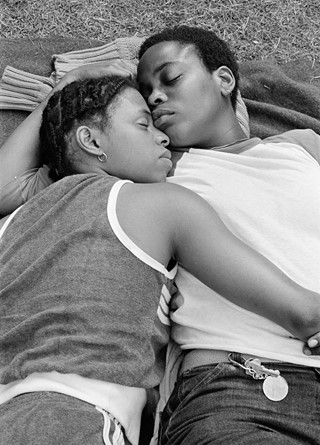

Today, Biren’s delicate portrait of lovers Priscilla and Regina, taken in Brooklyn, New York, in 1979, adorns the cover of Lewis’s new book, Photography – A Feminist History (Ilex Press/Tate). The book spans some 200 years, and over 140 practitioners, charting women’s origins in studio photography in the 1800s through to ‘selfie culture’ and Instagram aesthetics in the 21st century. Along the way, Lewis foregrounds some of the many women and non-binary photographers – hailing from all corners of the globe – who have been cast aside in favour of the few that made it into our history books.

“If you think about galleries, museums, the collector’s market, the publishing industry, all of these are commercial in one way or another,” explains Lewis. “And so the brutal reality is that women’s stories are made marketable – and some are more marketable than others.” When Lucy Rhiannon Cosslett covered Tate Modern’s 2019 Dora Maar retrospective (curated by Lewis) for the New Statesman, she exposed the way media headlines framed the exhibition in order to generate more clicks: namely, by contextualising Maar as the wife of Pablo Picasso.

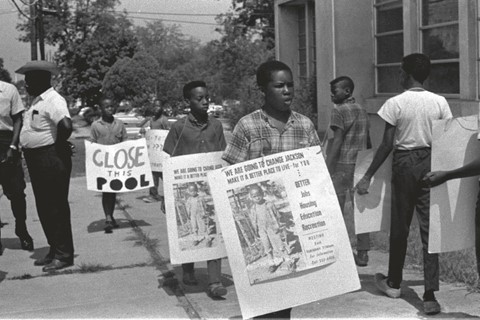

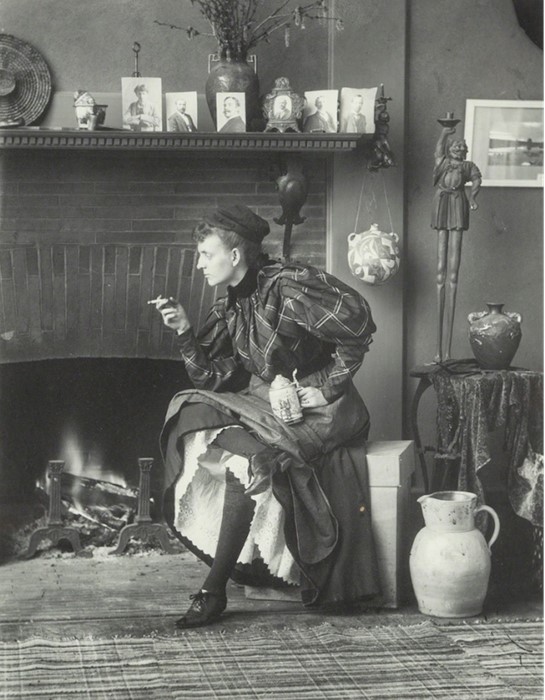

But clickbait culture exists to the detriment of accurate and nuanced accounts. A preoccupation with ‘marketability’ has seen the same stereotypes of women photographers throughout history emerge: our “genteel lady hobbyists”, as cited in the book’s introduction, or our “gung-ho pioneers.” Meanwhile, the thousands who don’t fit the mould – the working-class women who set up studios to make ends meet; the ordinary folk quietly recording their communities – fall through the cracks. “I wanted to get under the skin of that,” remarks Lewis. “I really wanted to interrogate it.”

What Photography – A Feminist History is not, however, is simply an anthology of women photographers. In an industry trying to work toward ‘inclusivity’, but often falling short, women’s work is still frequently denied the same claim to universality that men’s is; images by or of women are quickly read through a ‘feminist’ lens, irregardless of the whether the artist intended them to be. This was a pitfall Lewis was careful to avoid. In her words: “There is a difference between a photograph by a woman and a feminist photograph.”

So what makes a feminist history of photography? Chiefly, the book maps photographic developments against shifting gender rights and roles, exploring how photography has borne witness to women’s social and political movements – and how, in turn, feminism has given us new ways of understanding photographs.

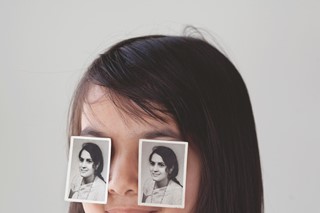

Across ten thematic essays, Lewis considers, among many things, how the abolitionist movement interacted with women’s entry into photography, or how work from avant garde artists of the 19th and 20th century – Lucia Moholy, Germaine Krull, Florence Henri – overlapped with notions of modernity and the ‘New Woman’. She contemplates how performative self-portraiture by Bolette Berg and Marie Høeg (Berg & Høeg), Frances Benjamin Johnston and Alice Austen preempted historic developments in queer theory in the latter 1900s, and how movements including the Feminist Sex Wars, race riots and disability activism gave rise to contemporary concerns of visibility and ‘representation’ – key motivations for artists such as Elle Pérez, Nydia Blas and Siân Davey. Other featured photographers, as well as Biren and Maar, include Poulomi Basu, Laia Abril, Lebohang Kganye and Mari Katayama.

After an illuminating phone conversation with Lewis about all of this, and more, I end on a question for her. Can (all) women ever have truly equal footing at the helm of a medium that has, historically, been so deeply rooted in our disempowerment? “Can we? Yes. Will it be a long and difficult journey? Yes.”

Photography – A Feminist History is published by Ilex Press/Tate and is out now.