Cuban-born artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres, who passed away in 1996 aged just 39 from AIDS related complications, created beautiful, subtle and moving installations relying on ideas current in conceptual minimalism...

Cuban-born artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres, who passed away in 1996 aged just 39 from AIDS-related complications, created beautiful, subtle and moving installations relying on ideas current in conceptual minimalism but imbued with a popular sensibility that spoke to a vast audience. His output was inherently based around an open conversation with his lover Ross, Gonzalez-Torres often stating he made his pieces for Ross first and a further audience second. Although only actually creating his body of work in a fifteen-year time frame, since his passing it has been repeatedly installed and exhibited internationally in a variety of contexts, from small local galleries to museums and biennials. This year's Istanbul Biennial has been curated around five themes and concepts that run through Gonzalez-Torres' artwork, focusing on other artists and their related conversation. Here, we bring together one of the biennial's curators, Jens Hoffman, with editor of Istanbul-based art magazine XOXO, Dincer Schirin, to discuss Felix, his relevance today and to an international audience inclusive of all backgrounds and cultures.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres' body of work was produced in a relatively short period before his passing, around 15 years of actual production. Since his death in 1996 his work has been reinstalled on a regular basis internationally. What do you feel it is about his work that has made it consistently relevant?

Jens Hoffman: I think it is a number of factors. His mostly minimalist aesthetic still has strong visual appeal and fits into a contemporary sensibility. The fact that something so elegant and handsome can also carry such radical content makes it even more appealing.

Dincer Schirin: To me, Gonzalez-Torres' works are always open to voyeurism as they involve such intimate narratives. We read what he gives us but we project ourselves into what we see rather than interpret it. He was also known for talking to the museum guards at his exhibitions, educating them about the work and inviting them to discuss it with the audience, changing the boundaries between museum and audience. Jens, while thinking about the audience's energy, how did you interpret this for the exhibition? How much do you know about Istanbul's local audience?

JH: What's most important to understand, in regards to audience, is the fact that we do not see ourselves as the ultimate authority on the interpretation of the works exhibited. Neither do we see this Biennial to be the final word on art or exhibition making. It is perhaps better to understand Biennials as a particular voice presenting various concepts of how to negotiate art and its relationship to the world.

DS: When you announced that the biennial's concept would focus on Felix Gonzalez-Torres' five different works, a discussion started. How do the curators make a connection between the biennial, the conceptual framework and Istanbul? Some of the local art scene have already been pessimistic about the lack of connection between these ideas. Do you think that the exhibitions should be about a connection between the biennial and the city and what do you intend to add to the history of Istanbul Biennial?

JH: There are many different ways of making connections and being site-specific. It would be dull if everyone just repeated one idea of what 'site-specific' means. I do not think that one has to have many venues all around town or talk about the exact political realties of a place to be context specific. That is why Gonzalez-Torres is so interesting to us. Through his work we offer a wider connection to issues like history, politics, identity or migration and mobility, all of which are subjects important in Istanbul but also around the world.

While Gonzalez-Torres' socio-political contexts are read and understood internationally, and they are in a variety of countries with differing cultural and religious ideals, there is a quiet nature to them. That quietness stems from his desire to go "under the radar", to make social and political points from within the establishment, seeing that as the only way to make lasting change. Do you believe his work and the reading and understanding of it has had a lasting effect? And if so, are they the changes he was trying to make?

JH: Gonzalez-Torres did not have it in mind to spoon-feed his ideas to the viewers of his works. That it a very important element of his work to keep in mind. The reason why he called his works Untitled is part of this position. The work changes in time and space and yet the subjects are so universal that in most cases they are perceived quite alike.

Do you not think he had a political/socio-political agenda?

JH: Gonzalez-Torres would have never said that he had an agenda. His way of voicing his political and social convictions was more subtle and complex than that. But you are right in so far as he wanted to make the world a better place, that is certain.

What affect do you think his work has had on contemporary art practice?

JH: I don't know if Gonzalez-Torres knew Herbert Marcuse's writing well, but in his last book Marcuse breaks from Marxist philosophy and argues against the Marxist view that art is a reflection of social class and only useful as a tool for revolutionary causes, and instead posits that art is a tool for transcendence. By evoking the beautiful and the utopian, art can influence how people perceive the world and inspire them to change it.

DS: Felix Gonzalez-Torres believed that meaning could be created by personal experiences with art. If we say that meaning comes from somewhere personal, thus political, could you please tell us how did you build up the politicality of the 12th Istanbul Biennial? If it is not talk to the city, by which I mean local art practice, do you think could it be a risk that the political discourses will not penetrate the audience

JH: The moment you or any other visitor comes in contact with art, a political act is being formed. You start reflecting about what is exhibited and presented in front of you. I am much more interested in that act as a political gesture than any form of visual representation of political situations in Istanbul, Turkey or anywhere else in the world. That is why the show is called Untitled, everyone can fill in that space any way they see it working for them.

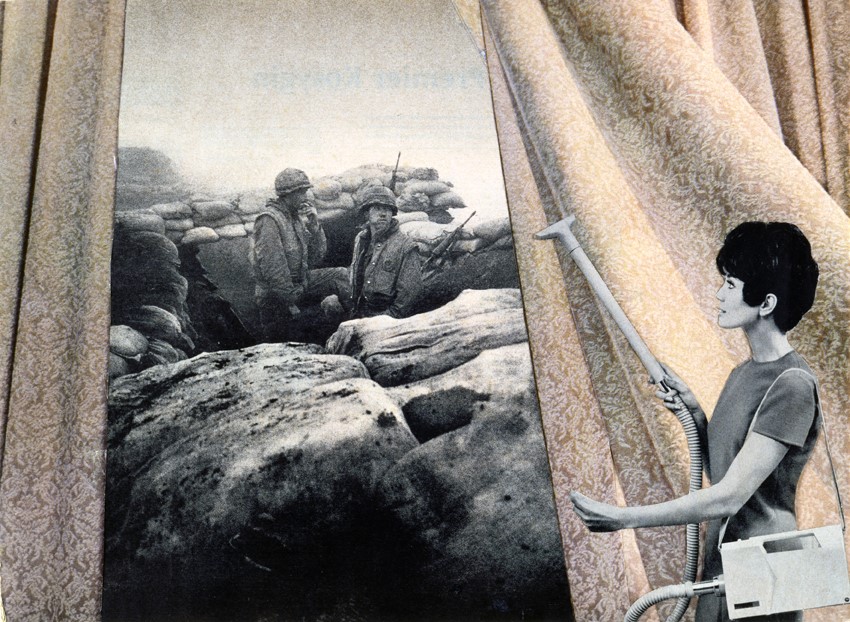

DS: I want to concentrate on the issues under the theme of Untitled, (Ross) which gives us a way to consider the notion of family, love, desire, and relationship. Coming from a practice interpreting minimalism and conceptual art with his own personal narratives, Felix Gonzalez-Torres stresses that aesthetics are political, that they are not talking about politics, they are politics themselves. Moreover, some of his works need to be updated when they are shown, for instance his own portrait, Untitled, 1989. What kind of concerns did you have while curating the updated Untitled, (Ross) section of the biennial?

JH: In the context of this exhibition, Ross becomes an emblem of themes of gay love, relations, family, identity, desire, sexuality, and loss – all of which are addressed in different ways by the works in the show. Our decision to have a rather obscure reference in this exhibition’s title is an homage to Ross and Gonzalez-Torres, as well as a way of blending the personal into the political through biographical and poetic means.

The Istanbul Biennial runs until November 13 2011

Text by William Oliver