Two back-to-back Japanese exhibitions highlight the photographer’s raw shots of sin-filled nights in 20th century Japan

The reactionary violence of capitalist state power that emerged in the wake of Tokyo’s 1968 student riots – and the grotesque urban transformations of post-war Japan at large – produced a generation of hard-bitten street photographers who created some of the most revolutionary photo books in the medium’s history: Shōmei Tōmatsu’s Oh! Shinjuku (1969), Takuma Nakahira’s For a Language to Come (1970) and Daido Moriyama’s Farewell Photography (1972), to name but three. Rather than seeking to develop a productive analysis of contemporary culture, they turned Tokyo’s cityscape into an inner darkroom where one staggered from desire to trauma, passion and rage, at a time when it seemed perfectly possible that Japanese civil society would crumble even more radically than in France or the US.

That said, these books contributed a great deal to the city’s iconography. And in the mid 70s, a special addition to this iconography came courtesy of an unlikely chronicler. Hailing from Chūō-ku in the heart of Tokyo, Seiji Kurata began his photographic journey when he was 30 years old. “One day when I was not so young,” he recalled, “I fell into a state in which my reality was dilapidated and ruin inevitable … Quickly turning off the television, unthinking, I reached out for a camera, that piece of optical apparatus.” Kurata took a gamble and quit his job at a thermostat factory in 1975; he subsequently joined the independent photography school Workshop, where he studied under Moriyama, no less. According to Kurata, it was here that he realised the profundity of the Japanese proverb “gei wa mi wo tasuku” (“an art saves the body”).

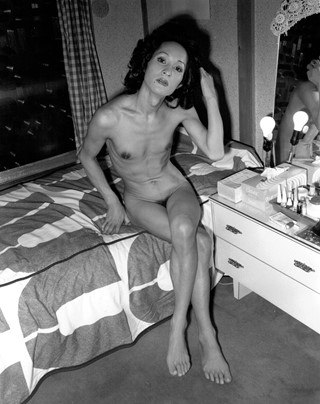

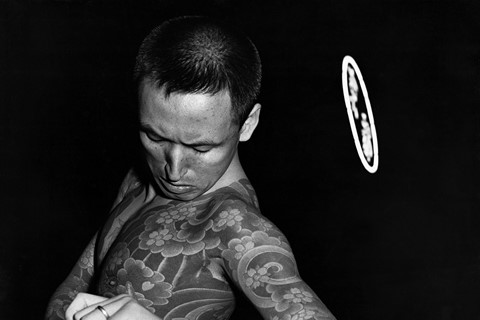

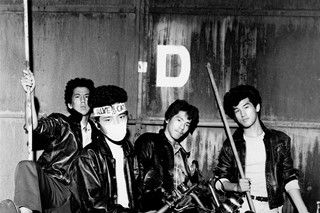

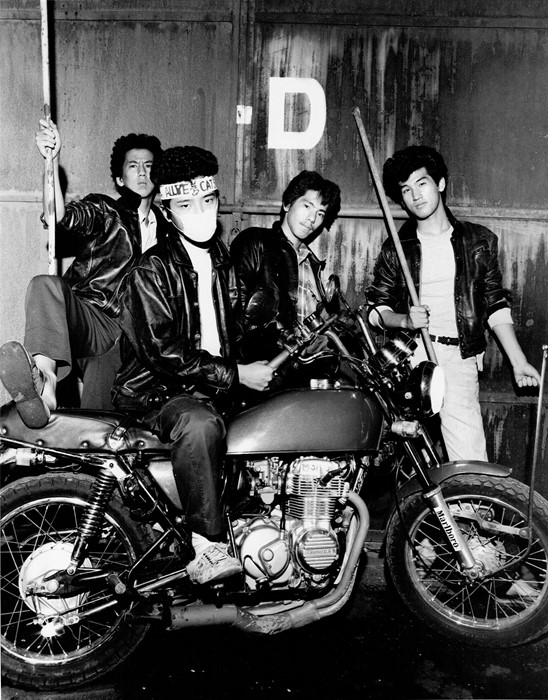

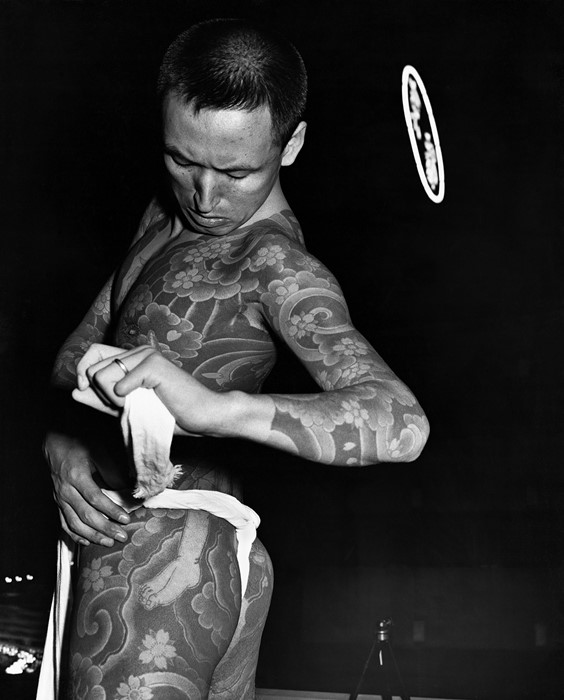

During his one-year-long seminar, Kurata began practicing photography with his medium format camera and strobe: they were his guide through the city’s seedy, sin-filled nights. Kurata’s beat was the entertainment district of Ikebukuro: its backstreets were “whirlpools of excitement”; places where the molten forces of tradition and modernity, spirituality and commerce clashed. Cabaret dancers, yakuza, Hell’s Angels, gender-nonconforming individuals, bōsōzoku riders and the ultra-right wingers of the Black Dragon Society were all lightning-struck by Kurata’s almighty strobe, and eventually found their way into his famed photo book-cum-nocturn Flash Up (1980). Many claim that it’s one of the best debut books of the era, and the unforgettable display of a tattooed yakuza on the jacket, posing proudly on a rooftop with a samurai in hand, has undoubtedly played a significant part in its cult status.

The works currently on display at Tokyo’s Zen Foto Gallery – where two back-to-back exhibitions, Night, Alleys & People and Lads & Gangs, have been staged to encompass the breadth of Kurata’s urban subject matter – are rarer prints which were left in the photographer’s studio when he passed away in 2020. Some are even outtakes of his more recognisable works such as Rockers Gang (c.1975) or Yakuza and Cat (c.1980s). Nevertheless, they all demonstrate Kurata’s astonishing antenna for scenes that do not so much tell stories as suggest them. “My camera’s range randomly expands,” he once said of his shooting process, alluding to Flash Up’s subtitle: Street Photo Random Tokyo. “Now, I follow instinct. Take whatever comes. I yield.”

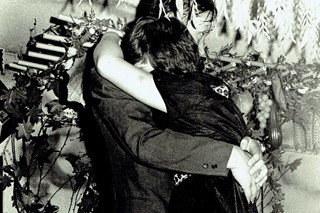

Crucially, Kurata’s camera was never ignored. It had the ability to be invisible but to provoke too: sex workers flaunted, dancers flashed, businessmen got drunk, brawls broke out, police officers intervened, lovers smooched. Here was a photographer who was always in and amongst it, and the haphazard yet attentive way he inscribed Tokyo’s denizens of the night onto photographic paper was unique. For example, while the elder Tōmatsu (who embraced a similar democracy of subjects) was a disillusioned chronicler of urban psychosis, Kurata was more sociologically interested – and, to an extent, invested – like his contemporaries Keizō Kitajima and Katsumi Watanabe, who made kindred records of Tokyo street life.

Yet the most frequent comparison that is drawn is with Weegee – dubbed New York’s “official photographer for Murder Inc.” – who also lugged around a formidable flash. However, it’s also the laziest comparison, for Kurata’s “flash ups” do not possess the lurid objectivism of Weegee’s crime shots. What Kurata pursued was the preservation of fear, desire and dissent – all within the memory of a photograph. And although Kurata later confessed that it would have been impossible to make his photographs outside the turbulence that was 70s Tokyo, he was also aware that the sentiments they contain are as old as time itself. As he wrote so evocatively in the afterword to a 2013 edition of Flash Up: “Even though it lasts only a moment, this brightly shining band that stretches across the sky can tell the story of all existence, all affirmed and all accepted.”

Night, Alleys & People ran at Zen Foto Gallery from 27 November – 25 December 2021. Lads & Gangs runs from 7 January – 5 February 2022.