As the groundbreaking artist and filmmaker dies, revisit this Another Man interview from 2019, in which Bidgood reminds us that “you have to feel art. It demands a physical response”

Born during the worst of the Great Depression in 1933, American artist James Bidgood displayed his love for glamour, fantasy and spectacle from a young age. “He begged his mother to buy him a paper doll set,” says Lissa Rivera, curator of James Bidgood: Reveries, now on view at the Museum of Sex in New York. “Despite the restraints on their financial situation, his mother bought one for him. Using his imagination, he turned an old cereal box into a technicolour masterpiece befitting a Busby Berkeley musical for the dolls.”

Now 86, Bidgood has forged a singular path throughout his life as a female impersonator, window dresser, fashion, costume, and graphic designer, photographer, stylist, and filmmaker. This remarkable career began when the young man from Wisconsin moved to New York in 1951 at the tender age of 18.

“The city was so clean, so bright and shiny then, the concrete sidewalks seemed embedded with glitter – they actually shimmered in the summer sun like they were like studded with tiny diamonds,” Bidgood tells Another Man. “New York was exactly as it appeared to be in MGM musicals. It was fast and it was more exciting than your second orgasm.”

Bidgood got his start performing as Terri Howe at Club 82, an East Village drag club, when it was illegal for men and women to cross dress on any occasion other than Halloween. “I always wanted to be on the Broadway stage,” Bidgood recalls. “When I made my entrance, all dolled up in glitter and soft, fat ostrich feathers, I imagined I was working the boards at the Ziegfeld Theatre playing to the balcony!”

During the late 50s, he attended the Parsons School of Design in Greenwich Village, and began designing costumes for society balls. “I knew little about the art world then; I still am not really very interested,” Bidgood says. “That sort of debate seems too political to me, too much about edicts and name dropping, too much about being included than the art itself.”

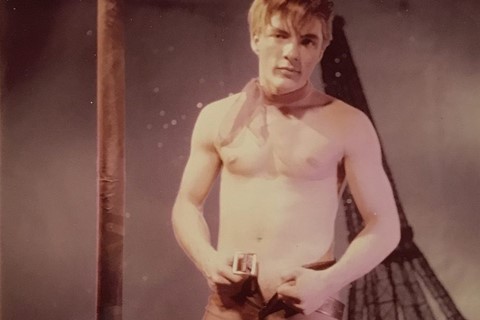

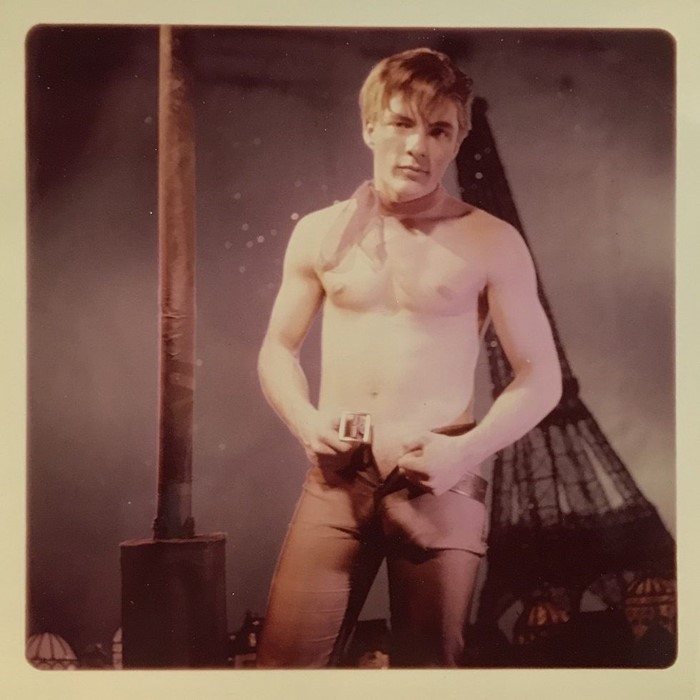

As an outsider, liberated from the constraints of the art market, Bidgood revolutionised gay male erotic imagery by applying the pulp and glamour aesthetics of the 1940s and 50s to “physique photography”, the highly coded gay pornography that carefully transgressed the censorship of full-frontal nudity, which was considered a crime of “obscenity” by the US government.

A stylistic precursor to Pierre et Gilles, David LaChapelle, and Steven Arnold, Bidgood’s work stands apart from his contemporaries, who embraced the mid-century tropes of the all-American male. He staged cinematic extravaganzas in his tiny Manhattan apartment for publications like Muscleboy and The Young Physique. “I wanted to photograph naked young men as opulently and as attentively as those professional ladies appearing in Playboy-type magazines were photographed,” Bidgood says.

“I knew my film could be confiscated being processed by Kodak if they spotted too much flesh colour while they scanned the processed film. However the surrounds in my photography were usually so elaborate those making these judgments were I think often confused. I usually covered the dangly bits with something like organza or china silk or stretch fabrics.”

Bidgood sometimes recycled materials he used in his commercial work designing costumes for society balls. “He would take the costumes home and those were the backdrops for his photos. In The Willow Tree, all the beautiful iridescent pastel branches, those are pieces of the skirt an heiress had worn,” Rivera says. “He was creating what he wanted to see, to elevate 18-to-25-year-old men who are realising they are beautiful for the first time.”

Bidgood was a natural, discovering innovative ways to explore, express, and heighten desire – making his work that much more seductive and romantic, particularly when compared to hardcore pornography. He remembers seeing a straight sex loop in a Times Square porno theatre where the woman covered a man’s penis with a silk scarf then proceeded to fellate him. It left a strong impression upon him.

“As long as whatever was not nude it evidently was legal. But legal or not, it seemed to me many times sexier, far more naughty than had it been bare,” Bidgood says. “This was more or less something I had already realised. It is very often what you don’t see that is the greater turn on because your mind fills in the blanks with what that particular viewer hopes they would discover.”

The culmination of his vision was realised in the film Pink Narcissus, depicting the allegorical fantasies of a gay prostitute, which became an underground hit when it was released in 1971. But Bidgood removed his name from the credits following creative differences with the film’s producer, and continued to work in obscurity until the late 90s when writer Bruce Benderson located him and helped produce Bidgood (Taschen), the artist’s first complete monograph.

Throughout it all, Bidgood remains true to his principles. “Art only stimulated by praise or profit is not art. If it is not born from pain or anguish or pride or shame or desire or overwhelming joy, it is only something of decorative value,” Bidgood days. “What is art should never be determined exclusively by those who can afford it. You have to feel art. It demands a physical response.”