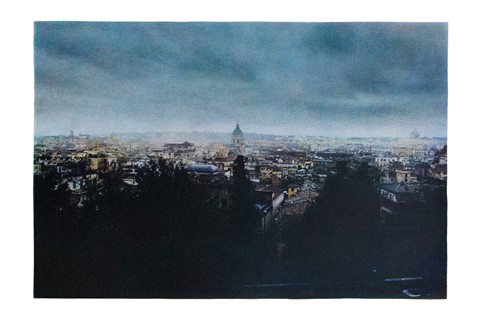

“I am sure Rome is the city where I shall come to die,” wrote Virginia Woolf in a 1927 letter to her sister, the painter Vanessa Bell. “I find the architecture divine. Pillars of pale green & pink marble like avenues of birch trees disappearing one behind another: immense distances; vast spaces; people like ants; everything very light, gay and spacious.”

The Bloomsbury Group – a group of 20th-century British writers, artists and intellectuals that included Woolf, Bell, Duncan Grant, Vita Sackville-West, and more – were enthralled by Italy. Kim Jones, artistic director of Fendi womenswear and couture, is likewise entranced by the Bloomsbury Group; for his first ever couture show for the Roman house last year, he honed in on Woolf’s gender binary-blurring 1928 novel Orlando, and the group’s love of Italy. The show featured some of the world’s most in-demand models – Kate Moss, Naomi Campbell, Bella Hadid, and Adwoa Aboah among them – Jones’s own Bloomsbury Group of sorts.

A year on, and Jones is still not done with the Bloomsbury Group. A hefty new Rizzoli tome, The Fendi Set: From Bloomsbury to Borghese, bears the fruit of an 11-month project undertaken by photographer Nikolai von Bismarck – something he describes as a chance “to add some depth and context to things Kim maybe wasn't able to express in the show and with the clothes.” Landscapes and still lifes of Woolf’s bedroom at Knole House, Duncan Grant’s studio at Charleston Farmhouse, the crumbling Colosseum in Rome and the winding staircases at the Villa Medici are interspersed with behind-the-scenes couture portraits of the models, actress Gwendoline Christie frolicking at the Bloomsbury Group's various hideouts, and handwritten letters and diary entries by Woolf, Bell and Sackville-West.

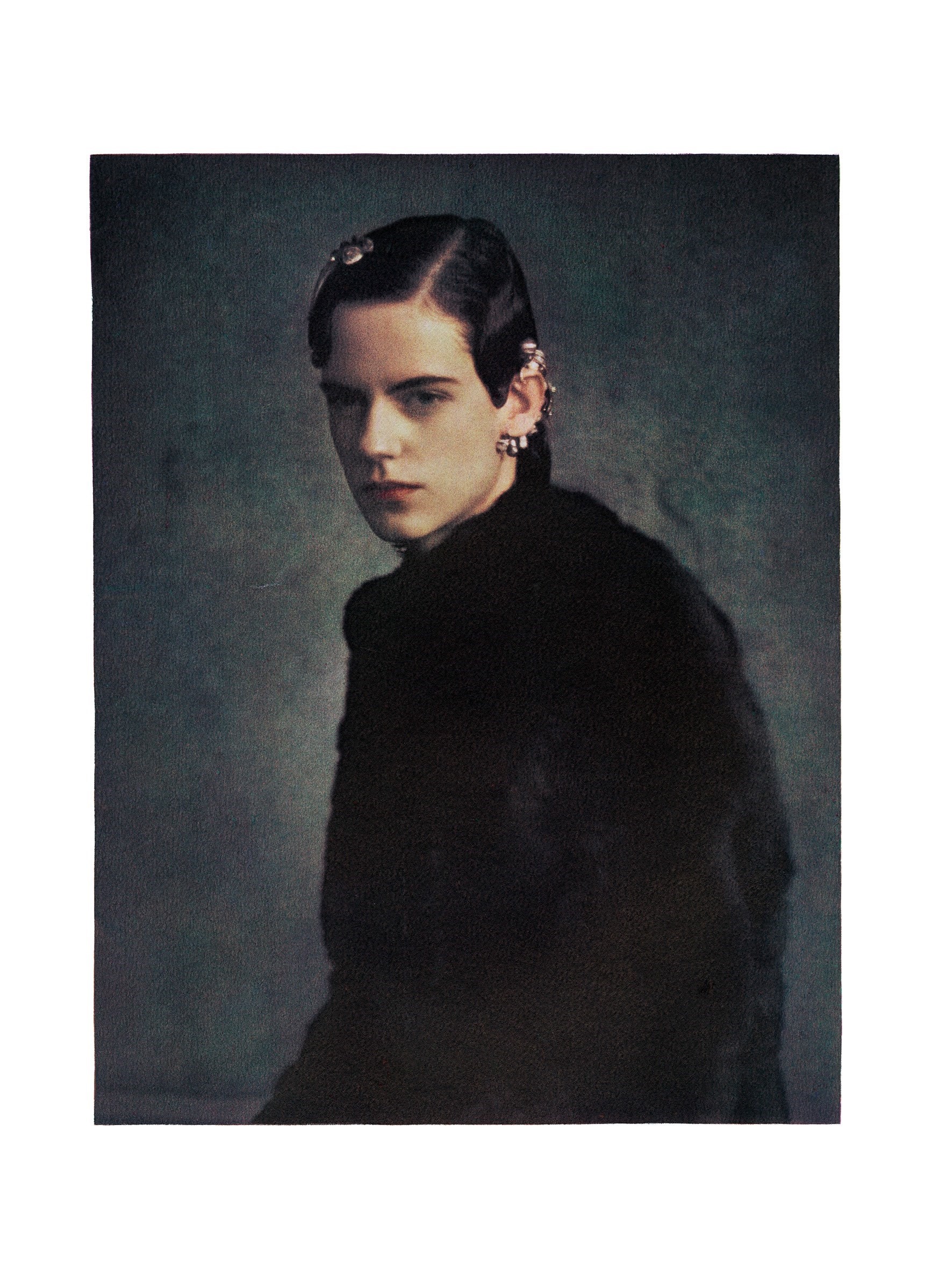

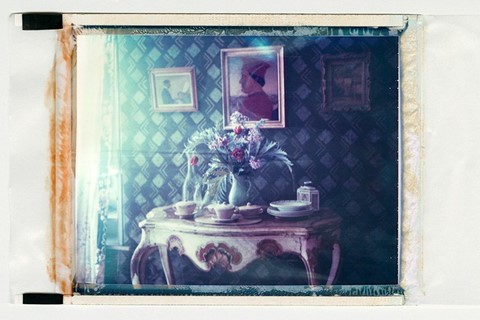

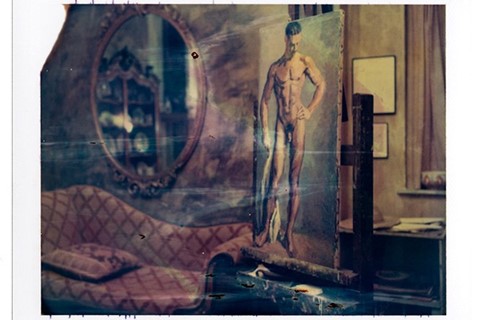

In the spirit of the era, Bismarck deployed a variety of old-fashioned, experimental photographic techniques: Polaroid, Super-8, and charcoal processes. “I wanted some of the Polaroids to feel like found photographs,’ says Bismarck. ”Something you might've just pulled out of a drawer, that could feel like they were from the time.” The resulting images are hallucinatory, antiquarian, a heady blur of old and new. “I wanted a ghostly atmosphere, a dreamlike quality,” says Jones. “Orlando is about time travelling and I wanted the work to transcend time, to drift between the present, past and future.”

In his own words, Bismarck tells us about embarking on project that would end up in print as The Fendi Set: From Bloomsbury to Borghese.

“Kim [Jones] asked me to do this project when we were in Scotland a couple of years ago. He’d just taken over at Fendi and had been saving the Bloomsbury Set for something special. I suppose he thought his first couture collection was the right moment to do it. I’m interested in [the Bloomsbury Group] too, but Kim takes it to another level. He’s got every first edition of every Virginia Woolf book, and furniture painted by Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell. He’s completely obsessed.

“Kim asked me to do the behind-the-scenes photographs for his couture fittings in the Fendi building in Rome in November 2020. Amanda Harlech was explaining couture and all the nuances, Alister Mackie was deconstructing the looks and then putting them back together, while Silvia Venturini Fendi and Kim’s relationship was really working. It was amazing, but it was lockdown in Rome. We were very much locked in that Fendi building, and we became Bloomsbury-obsessed. All day long, we listened to Max Richter’s Virginia Woolf album [Three Worlds] on loop. At lunch we would talk about Vita Sackville-West’s clothes and where Duncan Grant got his inspiration from. It was incredible to be in that environment.

“Around this time, I started meeting with Fendi to talk about the book. The idea was to add some depth and context to things Kim maybe wasn’t able to express in the show. We took his idea and expanded upon it. Jerry Stafford happened to be in Rome at the time, and he was at the fittings writing notes. At one point, we were walking around the Protestant Cemetery and came across Percy Bysshe Shelley’s grave and John Keats’s grave. Jerry remembered that those two were great heroes of Virginia Woolf’s. That was the lightbulb moment – OK, there are links between the UK and Rome.

“From there, we began looking up whether Duncan Grant spent time near Rome, and it turned out that he’d been given a grant by the Villa Medici to live and stay there. He also had a studio on the via Margutta in Rome. Vanessa Bell stayed in the Hotel de Russie and wrote letters back to her sisters. We were suddenly diving in deep and finding all these amazing references. Then we reached out to the Charleston Trust and they pointed us in the direction of Dr Mark Hussey, an amazing Bloomsbury Set scholar. He helped dig out the actual facsimile letters that are in the book. It took us on an incredible journey. Mark was saying it wasn’t an area that had been explored that much, the Bloomsbury Set and Italy. He was fascinated because he was finding out all these new things he didn’t know. Those letters and quotes, particularly in Rome, began to lead the photography.

“I used the charcoal process, where it takes seven to ten days to handprint one picture. The process is done by a French family; it’s been in the same family since the 1890s, and it’s been passed down through the generations to Jean-François Fresson. In 1952 they developed a colour charcoal process. Jean-François is the last of his family to be doing it, and it’s kind of amazing that he agreed to do it. It took months of trying to persuade him to do it as he doesn’t work very often. Then we were sending packages back and forth between London and France with these prints. We’d wait for three months for ten pictures. It was incredible and worth the wait. What an experience to work with this legendary family.

“It was amazing to use these processes that won’t be around in ten or 20 years. These Polaroids that run throughout the book, it’s on its last legs. Half of the photos we were taking in Paris of the girls were coming out blank, the chemicals were all dried up. You were getting dud photos when you had ten minutes with Demi Moore, under severe pressure. It was amazing to use these processes before they fade, and to make something permanent like a book out of it, so they’re forever kept in something bound.

“Inspiration-wise, I was looking at Julia Margaret Cameron’s work. She was Virginia Woolf’s great aunt, and was taking pictures in the 19th century. Her work is quite ghostly and was a big inspiration for the book, because of Sally Mann. It lent itself well to the Bloomsbury Set, that ghostly, quite eerie, quite dark, gloomy mood that they have. Quite tense. I wanted some of the Polaroids to feel like found photographs. Something you might’ve just pulled out of a drawer, that could feel like they were from the time. To really show that these places aren't just museums, some of them are kept beautifully. I wanted to give them a feel of having just been lived in. The pictures of Virginia Woolf’s bed, it felt like she was there not that long ago. I wanted to give it a sense of romance, which comes through in all their work. I like to think the photos reflect the palette of Duncan Grant’s work; those very soft, warm tones that run through the book.

“The book was long and it was arduous, but it was incredible to work like that through the pandemic. I’m very grateful to have done it, to have been given time, which so often you’re not. Time to experiment and time to use processes that take weeks to get one photo back. This book has really improved me.”

The Fendi Set: From Bloomsbury to Borghese is published by Rizzoli and is available to buy now.