By focusing on Louise Bourgeois’s use of fabrics and textiles, the Hayward’s new exhibition showcases the late artist’s raw depictions of sexuality, trauma, memory and reparation

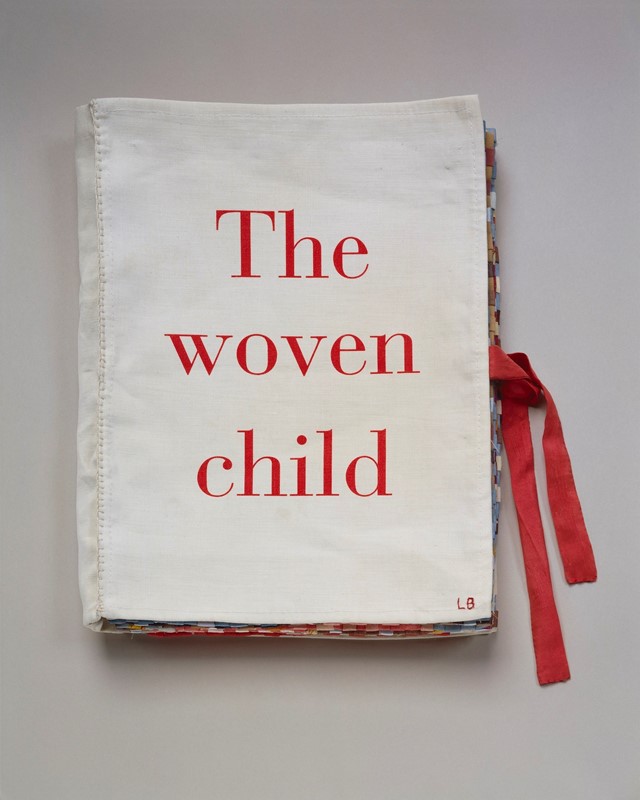

“I am not what I am, I am what I do with my hands,” once said artist Louise Bourgeois, whose seven-decade career encompassed a variety of mediums and whose influence remains prolific. Now, 12 years after her death, the Hayward Gallery presents The Woven Child – the first major retrospective to focus exclusively on her work using fabrics and textiles.

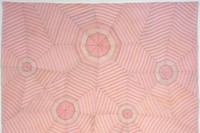

It features installations, sculptures, and collages made from materials such as handkerchiefs and bed linen. There are some of her Cell installations from the 1990s, each containing personal objects relating to her childhood. There are also four large vitrines – glass cabinets containing fabric sculptures – exhibited alongside one another. Her work is heavy with themes of sexuality, trauma, memory and reparation.

“Some of my favourite works are the depictions of individual figures, torsos and heads, which are so emotionally charged that it is as if they have been turned inside-out; vulnerable and exposed,” says Katie Guggenheim, assistant curator of The Woven Child. “It is amazing how powerful these sculptures can be, some of them so small and doll-like, hand-stitched from old scraps of fabric.”

While it was the later decades of Bourgeois’ career that saw her use clothes in her work, fabrics had been part of her life since her early childhood in Paris. Born in the city on Christmas day in 1911, her family owned a gallery that dealt in antique tapestries, and later ran a tapestry restoration workshop where Bourgeois helped with the repairs.

This, paired with Bourgeois’ richly narrative approach which frequently connected her work to childhood memories, traumas and pain – she considered this a means of therapy – indicates how much weight fabric has held, literally and metaphorically, over the course of her life and career. Many of the materials used in the works are those which Bourgeois had hoarded from as far back as her childhood. “The fabric works are so powerful in their materiality,” says Guggenheim. “The fabrics she used – old clothes, domestic towels and bed linens – are the kinds of fabrics that are in close proximity to our bodies and so they have sensory associations that are linked to deep-seated emotions and memories.”

There is also a focus on needlepoint: a skill close to Bourgeois’ heart. “I have always had a fascination with the magic power of the needle,” she once said. “The needle is used to repair the damage. It’s a claim to forgiveness.” Bourgeois also felt that needlework was a visceral response to her fear of abandonment: “The sewing is my attempt to keep things together and make things whole.”

Needlepoint is also, historically at least, a domestic skill mastered by women. Bourgeois was deeply concerned with the role of women and their identity throughout her career. For this reason, The Woven Child feels especially timely in 2022, even if many of the works were created in the 1980s and 1990s. Today, the injustice of gendered division of labour is slowly beginning to be taken seriously, and yet there is still no professional and financial parity for women, making it difficult for them to sustain or progress in their careers when they become mothers.

Guggenheim points out that much of Bourgeois’ work was overlooked until she was in her eighties. “This was not only because of her gender but because of her role as a mother, wife and daughter, within specific social milieus in Paris and New York. Bourgeois made ambiguous and ambivalent statements about feminism and she didn’t align herself with any political or social movements but it is clear from her work that she was extremely aware of the misogynistic framework that she was operating within.”

Bourgeois’ influence is vast and can be found in works by Tracey Emin – most notably her quilts and tents. Guggenheim cites Cathy Wilkes’ use of figures and textiles as well as the drawings and sculptures of Camille Henrot as having been influenced by Bourgeois. “I am also reminded of an installation piece by Park McArthur from 2014 which consists of worn pyjamas draped over steel armatures,” she says. “There is a strong visual relationship to Bourgeois’ ’pole’ pieces in which old items of her own clothing are hung from cattle bones, suspended from metal poles.”

It’s not just artists who borrow from Bourgeois – designer Simone Rocha has been vocal about how much the artist has shaped her career having first seen her work at The Irish Museum of Modern Art when she was a teenager. Since then, Rocha has collaborated with the Louise Bourgeois studio for her Autumn/Winter 2019 collection and, along with Hauser & Wirth, created a pair of earrings inspired by Bourgeois’ work.

Guggenheim believes that part of Bourgeois’ enduring appeal is simply down to the length of her career – seven decades of work has crossed generations and artistic movements – but that is the humility of her work that touched people most. “She addressed some of the most fundamental aspects of human experience: what it feels like to be a body in the world, the experience of physical and emotional pleasure and pain, how our lives are interwoven with others, and the complexities of these interdependencies. All of this helps to give the work an immediacy that makes it feel very contemporary and relevant today.”

Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child is open from 9 February – 15 May 2022 at the Hayward Gallery in London.