Robert Freson assisted Irving Penn for 13 years – here, he recalls how the late American photographer distilled the soul of his subjects in gelatin silver prints

After World War II, Belgian photographer Robert Freson arrived in New York City with a suitcase and just $100 in his pocket, ready to start a new life with his American wife. At the suggestion of his mother-in-law, Freson brought his portfolio to a building on Lexington Avenue where many Condé Nast photographers had studios. He met with the manager of VOC Studios, who was suitably impressed, but told Freson in no uncertain terms, “Don’t call us, we’ll call you.”

Suffice to say, she actually did. Two months later American Vogue sent Freson a telegram asking him to get in touch about a possible position that turned out to be the job of a lifetime. Legendary photographer Irving Penn had just returned from Peru, and needed someone to print the portraits he made in Cusco – the rest is history.

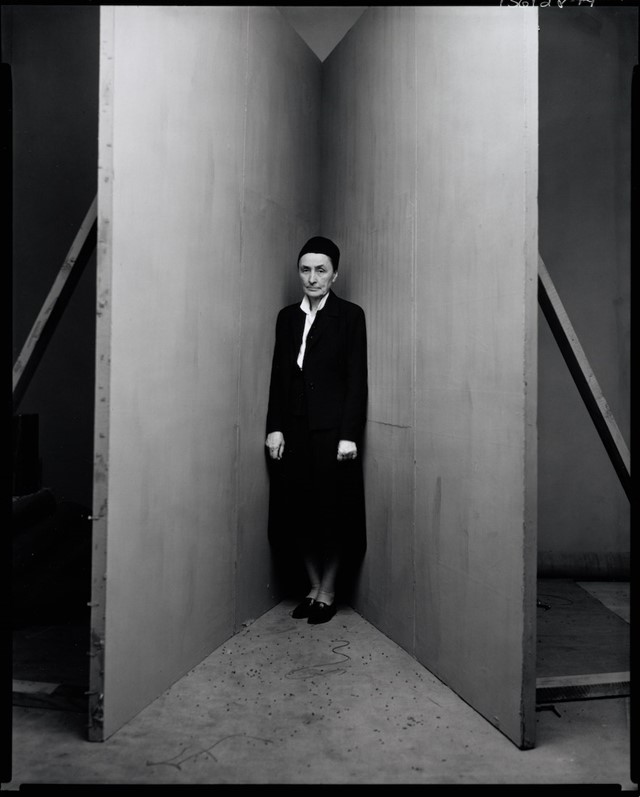

Now 95 years old, Freson has just gifted Bowdoin College Museum of Art with 16 photographs made by Penn that demonstrate the photographer’s brilliance as a portrait, fashion, and still life photographer. Whether shooting luminaries including Pablo Picasso, Miles Davis, and Georgia O’Keeffe, the latest looks from Balenciaga, or the Asaro ‘mud men’ of New Guinea, Penn distilled the soul of his subjects in gelatin silver prints.

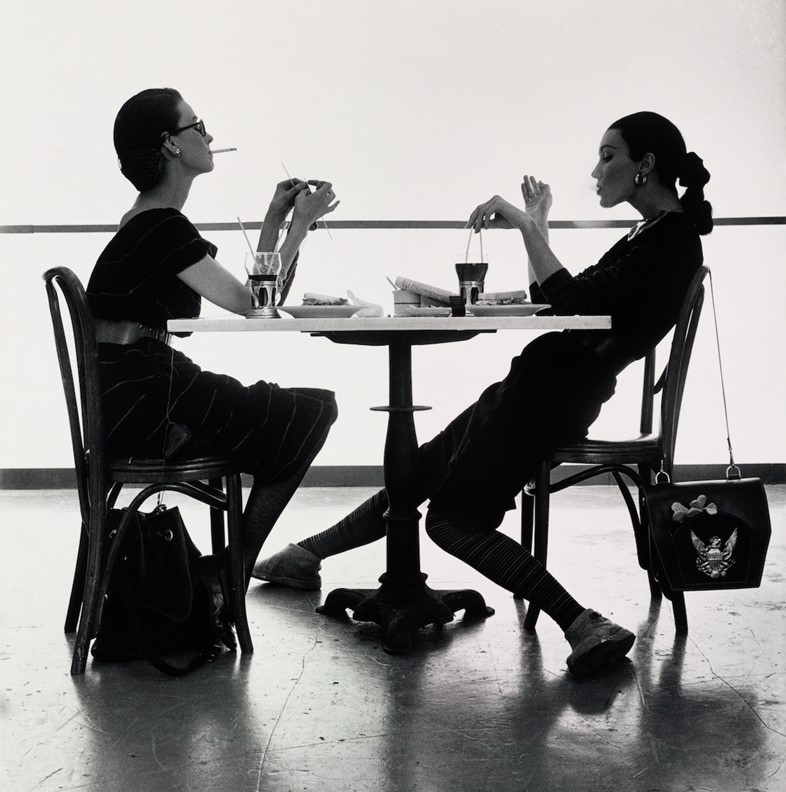

From 1949 to 1962, Freson worked closely with Penn as photo assistant then studio manager, just as the photographer was reaching new heights. Vogue art director Alexander Liberman recognised in Penn “a mind, and an eye that knew what it wanted to see,” and began sending him around the globe on portrait and fashion assignments.

Freson was Penn’s right-hand man during this time. “We travelled to quite a few places in Europe to do the collections twice a year. He always wanted me to come with him and left the other people in New York,” Freson tells AnOther. “Penn was very professional, private, and generous. He was quite conscious that I was aiming to eventually go on my own to be a photojournalist and he supported that. He let me use the studio on my own in the evenings and on weekends. He was extremely intelligent and very restrained in showing his knowledge. He was a good listener and always let people talk.”

Penn’s ability to be still and observe made him the consummate portraitist. “He had his own method: very isolated in studios or sometimes on location,” Freson recalls. “It was just Penn, the subject, and I. No unnecessary sounds. He would concentrate by speaking to them very peacefully while sitting on a high stool behind the camera.”

But sometimes the setting could be vibrating with an energy all of its own. While visiting Picasso’s Cannes studio in 1957 for a shoot, Freson remembers the incredible vitality the artist and his work radiated. “It was like you had a battery and you were getting charged by him,” Freson says. “We had that with Francis Bacon, TS Eliot, and many others, too. They radiated creativity and intelligence, and you could not help but soak it up like a sponge. I was quite young and had a lot to learn. I would never have been exposed to a lot of things if I hadn’t been working with Penn.”

Freson, who went on to work for Esquire, National Geographic, and the Sunday Times, learned a tremendous amount assisting Penn for 13 years. Freson credits Penn’s training as a painter in helping shape the artist’s approach to the medium of photography. “Penn was very aware of the chiaroscuro quality of the light,” he says. “Most of the work was done with daylight, but sometimes he duplicated that kind of light in the studio with artificial light so that we could work any time of the day.”

Using the camera as a painter wields a brush, Penn was always open-minded and ready to experiment. “He was very ambitious to discover new methods as well as old practices of photography,” Freson remembers. “He would go back to the beginning to explore old methods that had been eliminated by then because there was no longer a need for them.”

Penn’s innovative approaches not only advanced the medium but made him highly sought out by advertisers wishing to follow his lead. “Agencies usually come to photographers asking them to realise a project they have already developed and sold to a client,” says Freson. “But with Penn it was the other way around. They would come and talk to him, and Penn would make a little sketch showing them what he would do. They would bring that back to the client, who would say, ‘Fantastic! Let’s do it.’”

60 years after leaving the studio to work as a photojournalist, Freson says Penn’s photographs continue to inspire him. Whether it’s images of Marcel Duchamp, Jacob Lawrence, and Louis Armstrong, a street cleaner or street photographer, Penn’s images only get better with time.

“Penn’s photography was very honest,” Freson says. “Penn knew all about the people he photographed and was able to lead the conversation to get people to react to him. Then he would photograph them. Once he established the circumstance to make the photograph, he would stay with it. At a certain point, he got through to the reality of the person behind the facade – and that moment is valid forever.”