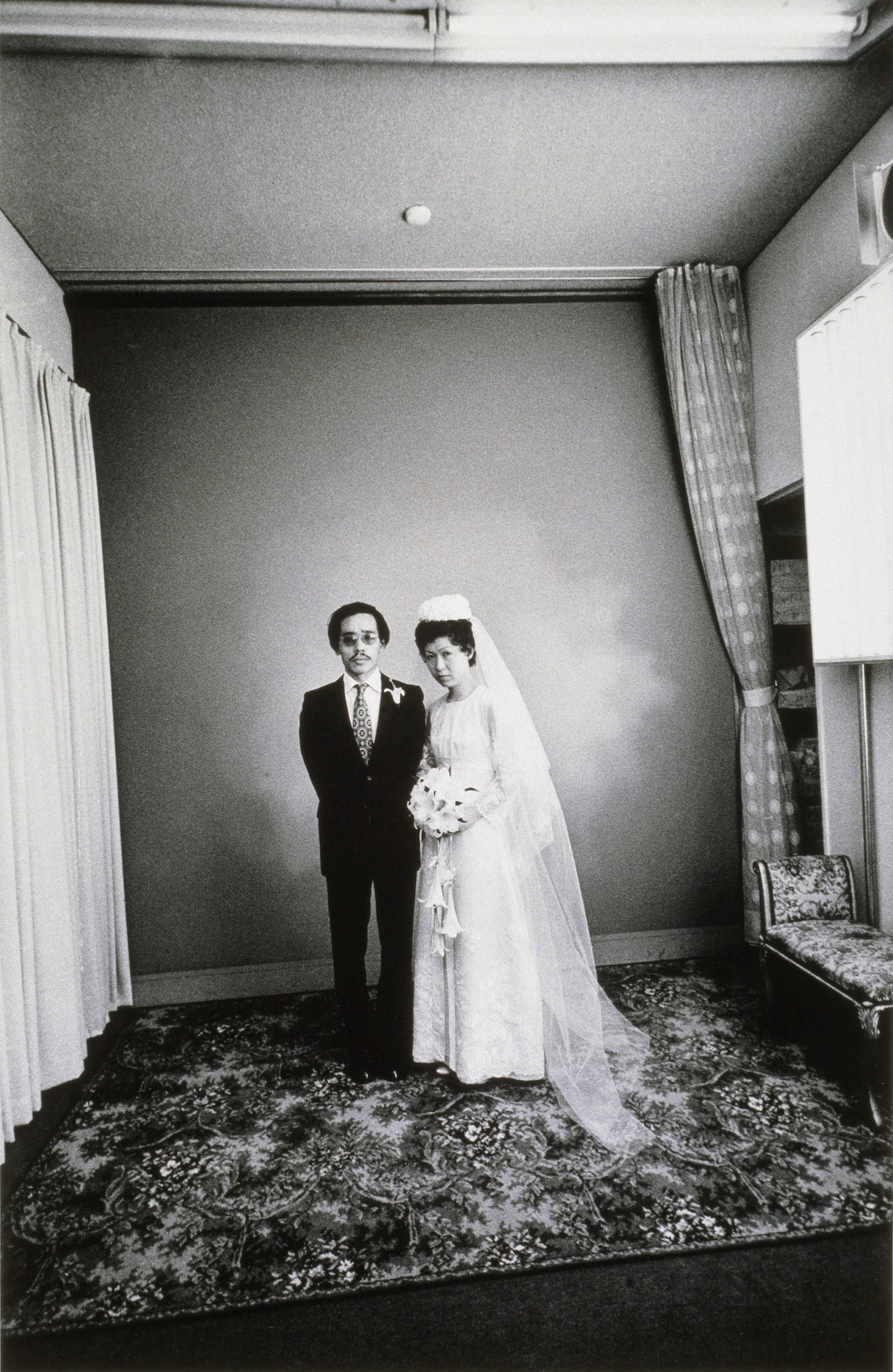

Taking Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1986) as its starting point, Love Songs, a new, poetically-charged exhibition staged at Paris’ MEP (Maison Européenne de la Photographie) is structured like a musical compilation devoted to a lover: ‘Side A’ comprises photographs dating 1950–1990, and ‘Side B’ 2000–today. While Nobuyoshi Araki’s Sentimental Journey (1971) and Goldin’s Ballad – two bodies of work that marked watershed moments in the history of photography – form key presentations, the exhibition prevails for its highly-intuitive curation, with greats such as Emmet Gowin, Larry Clark and Sally Mann in company with contemporary image-makers like Leigh Ledare, Hideka Tonomura, Motoyuki Daifu, Collier Schorr and Karla Hiraldo Voleau. Together, they tell a history of photography through the lens of love.

In his own words, MEP’s director Simon Baker introduces his curation, discusses its many notes, and reflects on the joys and complications involved in photographing – and being photographed by – the beloved.

“When we are in love, we do not always see clearly. We may think we do; that the object of this most mysterious and powerful emotion is this way, or that way; beautiful, handsome, sexy, funny, charming, whatever … but given time, distance, objectivity, (any kind of perspective at all, in fact), we may come to realise that things were not exactly as we imagined them to be.

“When we are in love, the person we love is the centre of everything, not only in the sense of being the focus of our thoughts, dreams and desires, but in the sense that we see everything through the prism of our love for that person.

“When we are in love, we would give up everything, burn down the world, for someone who may never even realise the ways in which they have rewired our hearts and brains; who may, if they knew, be mystified, or even terrified, by the effect they have on us.

“When we are in love, images of our lovers take on a significance and power that it is almost impossible to explain. We look again and again at their faces, searching for something that may only be a part of us, even if it is, finally, the best of us.

“When we are in love, we might still admit that, in fact, we don’t know what love is, what it is supposed to be ‘like’; that we don’t know what it ‘looks like’, and we don’t know how it makes us ‘look’ at things. When we are in love with someone to the point that our worlds have been turned upside down and inside out, to the point that we have difficulty even recognising ourselves, we might not be capable of thinking, writing or seeing clearly at all.

“Once, in Tokyo, I was with Araki. We were looking at the catalogue of a show that he had in Paris at the Musée Guimet. As we were leafing through the book, he stopped at a photograph of his late wife Yoko, the love of his life, which, he said, had always been his favourite of her. Then he said something more complicated about his practice. As ever with Araki, whose language in Japanese is riddled with jokes and double entendres, the translator struggled to explain what it was that Araki had been saying. But it was something like this: ‘In all my time with Yoko, I had thought that I was photographing love, that it was the subject of my work, but finally, when I look at these photographs of Yoko, I think that love is missing, that somehow I failed to capture it.’

“Love Songs presents a history of photography through the prism of intimacy. Bringing together series by some of the most important photographers of the 20th and 21st centuries, it shows both the importance of this idea to artists working now, as well as its rich history. At the heart of the exhibition are two landmark series: Araki’s Sentimental Journey and Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, each of which, in its own way, offers a unique and brilliant account of intimacy. Love Songs is a proposition about the nature of photography: the fact that, although the camera is often believed to be ‘objective’, it has frequently been used to record something about which we can find almost no agreement, objectively speaking; something entirely subjective. We may not agree on what love is, or how it is supposed to look, how it makes us look or how it makes us see, and yet it has been the subject of some of the most significant and powerful photographic work of the past century.

“‘Side A’ begins with René Groebli’s Eye of Love, made in the 1950s, which predicts many of the signs and conceits of Araki’s Sentimental Journey, while remaining true to the photographic style of the previous generation. Groebli brings us into the domestic and romantic spaces of intimacy, both in the sense of being deliberately close to the object of his affection, but also in the sense of being close to the things that that person has touched and even the way they touched them. In Groebli’s work, we have a photographic rendering of this same powerful and compulsive beauty, wherein we start to see the world of love through his eyes, by attending to the details of intimate daily life. Groebli, we could say, engages in a kind of subversive ‘familiarisation’ as we find ourselves, as viewers, in spaces and situations that inevitably belong to the very present [but invisible] photographer.

“This sense of being invited into the private and personal spaces and lives of photographers is shared in many of the series in Love Songs but in surprisingly different ways. While, with Alix Cléo Roubaud, we appear to witness a series of brief encounters in beds or bedrooms with her partner, Emmet Gowin allows us to follow the long and increasingly intense love story of a lifetime spent with his wife Edith.

“Elsewhere, there are some magical, almost performative, collaborations, such as the tender and poetic portraits made by Hervé Guibert of his lover Thierry, both of whom would tragically die of Aids within months of one another. Nowhere, however, is the intense emotional risk involved in intimacy more powerfully present than in Goldin’s Ballad, which remains, to this day, not only one of the most significant bodies of photographic work of all time, but continues to pose the questions which are central to the exhibition: if artists are never voyeurs in their own lives, what spaces do they offer us as viewers to make sense of the intimacies they share with us?

“Side B’ of Love Songs brings these questions up to date, often with an increasing complexity. Because, sometimes, as with RongRong&inri or JH Engström and Margot Wallard, we are offered both sides of the coin, as a duo of artists photograph their relationship together, from its inside and from both points of view. Both couples depict the first moments of their love, which, in the case of RongRong&inri, flourished despite no shared verbal language. The works in the show are photographs surrounded by messages written in Chinese characters which both could read, but, when spoken aloud in either Japanese and Chinese, it would have been impossible for the other to understand.

“I think the reason my curation of this exhibition constantly brought to mind the idea of the mixtapes or compilations offered between lovers [the reason why it has a ‘Side A’ and a ‘Side B’] is the sense of being immersed in the emotional landscapes of people we know through the words, ideas and emotions of people we do not. In choosing a playlist of songs that mean something to us by singers whom we admire, we are, in a way, offering the feelings expressed to our lovers as our own, as what we’d like to say – or, at least, what we would say if we could write music as beautifully as the songs that have been the soundtrack to our romantic lives. By doing this intimate curatorial work and sharing it, we permit ourselves to say things that we rarely say, or say badly, through a kind of appropriated poetry: ‘You see this guy? This guy’s in love with you. Bad choice? Maybe. Maybe not. Another one? I’m not the kind that needs to tell you, just what you want me to.’”

Love Songs runs at MEP, Paris until 21 August 2022.