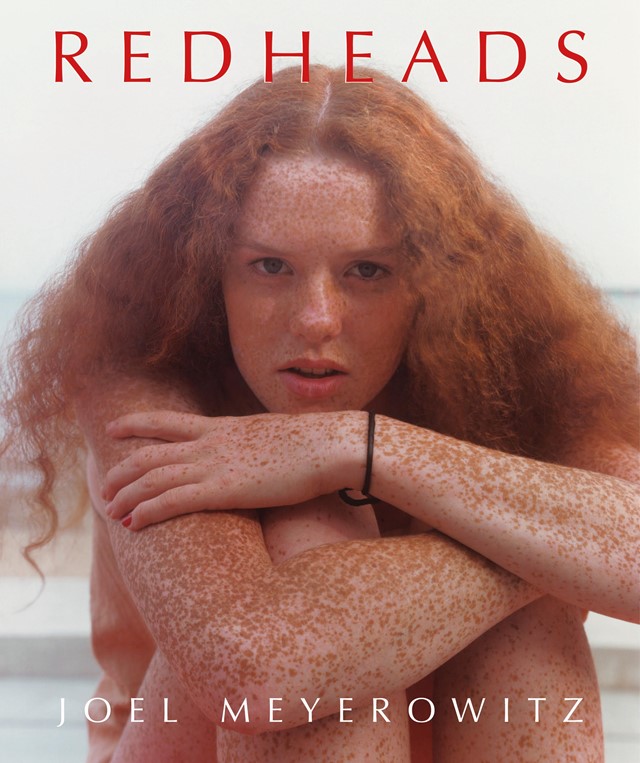

The American photographer reflects on his newly republished 1991 book, Redheads: a collection of portraits, taken over a decade, that celebrate ginger people of ages, races and genders

For Joel Meyerowitz, ginger people are like rare tropical fish. The photographer makes the admission in his 1991 book, Redheads, which is being republished this year by Damiani. In an evocative essay scattered throughout its pages, Meyerowitz attempts to grasp the aesthetic allure of the redhead. Their skin, he writes, is “exotic“ and “transparent as fruit”, bouncing off their hair and vibrating under the beams of the sun. He compares them to wide-eyed Minoan goddesses, frolicking wood nymphs, and mysterious sea creatures. “I had begun making portraits with the intention of photographing ordinary people,” he writes. “Redheads, it turns out, are both ordinary and special.”

For anyone who actually grew up with red hair, this could easily be read as sarcasm. After all, while the colour may be trending (a slew of influencers have recently been seen with bottled-dyed copper tints, while Vogue itself claims the colour is “having a moment”), it hasn’t always been seen as appealing. As someone with freckles and auburn hair, my childhood was at least partly defined by strangers shouting “ginge!” from bus windows, or making jokes about my “carrot top” (as well as the rest of my body hair). For those with more vivid hues of orange, the stories were much worse. Meyerowitz is aware of this, too: “I would ask everyone who I was taking photos of, ‘what was it like growing up with red hair?’” he tells me over the phone from his home in London’s Dartmouth Park. “For most people, it was torture.”

Meyerowitz, now 84, began making Redheads in 1976, during a summer vacation in Cape Cod. The photographer had recently acquired a large-format view camera and was looking to experiment with portraiture: a more considered, intimate practice than his signature, snap-and-run street photography. “I started to make a few portraits, just by chance, and I noticed that an unusually large percentage of these were of redhaired or freckled people,” he remembers. It was their heliotropic quality – the way their hair and skin were transformed by the summer weather – that Meyerowitz found most compelling. “The sun ignites redheads: the hair gets brighter, the skin gets freckles showing up. And maybe that kind of colouration played a role in catching my interest. But [I didn’t notice] the pictures [until] the end of summer. I thought to myself, ‘wow, I was hitting on redheads more than 40 per cent of time’.”

From there, Meyerowitz decided to follow his instincts. He resumed the project each following summer building a portfolio of sun-kissed titian-haired Americans of all ages, races and genders. Given that redheads make up only three per cent of the world’s population, this was a slow and steady project, spreading well over ten years. Meyerowitz ran ads in the local paper for “remarkable” gingers, approached passersby, and asked friends of friends if they knew anyone suitable. He would then take their photo, often with a backdrop of aquamarine skies and sun-dappled sea.

While taking their portraits, Meyerowitz would talk to his subjects. In the book, he notes that he was struck by their “courage and shyness”, as well as their shared “painful remembrances” of childhood. “I noticed kind of familial qualities [with people that belonged] to this genetic package,” the photographer says of his redheaded subjects. In the book, he calls it a “blood knot”: a tight bond between people who had to overcome being ridiculed or singled out while growing up. Bullying, to varying degrees, seemed to be a standardised part of the ginger experience. “On the flip side, almost everyone that I spoke to said, as they grew older, they began to feel much better about this singularity,” he adds.

The project also marked a major shift for Meyerowitz creatively. He began to fall in love with the intimacy of portraiture and the intense, erotically-charged – though not necessarily sexual – connection that would spark between photographer and subject. While street photography was created on the fly, these slow-shutter images took time and required more probing observation. “I began to really look at people and see beyond the colour of their hair or freckles,” he says, carefully. “Summertime is a time when we get naked. It was the sense that people were totally exposed ... much more part of nature.” Meyerowitz is quick to stress that he doesn’t mean this in a sleazy way – instead, he says, it is about a much deeper, more elusive bond. This kind of photography is a “two-way trip”; a way of coming close and staring openly; of unravelling the mysteries of another person.

The connections still exist, even three decades after the images were first created. When asked finally how he feels looking back at these photos now, under the bleak drizzly skies of London, I can almost hear Meyerowitz’s mind drift back to the moments they were taken. “I could tell you where I was, the quality of the day, the feeling I had when I made the photograph,” he says. “There’s so much intimate data we think we forget that the picture embodies ... It’s like I have a pathway back to a moment of crystallisation between me and an action, or me and a person. It is so rewarding. It’s like a continuity between the past and the present.”

Redheads by Joel Meyerowitz is published by Damiani, and is out now.