A painting of conjoined twins in delicate sky-blue gowns; a pair of tapering, cowhide stilettos; a rotating sculpture of tumescent, organic forms in bronze: these are just some of the magical works selected by Simone Rocha for her new exhibition girls girls girls at Lismore Castle Arts.

Canonical names like Louise Bourgeois, Cindy Sherman and Alina Szapocznikow feature alongside emerging artists including Josiane M.H. Pozi, Cassi Namoda and Luo Yang in a showcase of Rocha's wide-ranging, intuitive taste. “I wanted to pick artists whose works, to me, had this almost subversive, very provocative and visceral interpretation of femininity,” explains Rocha, just a few weeks after her bewitching Autumn/Winter 2022 show at London Fashion Week. Initially thinking she would curate an exhibition of photography, Rocha’s scope gradually widened to include sculpture, film and textile work, as well as images by trusted collaborators such as Roni Horn, Petra Collins and Harley Weir.

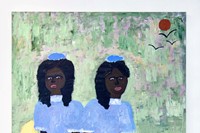

Perhaps that's why many of the artists involved feel like kin. The revolving bronze sculpture, for example, is by Bourgeois, an abiding inspiration whom Rocha often refers to in her work (and with whose estate she has worked on limited edition earrings). Other artists, like Cork-born Dorothy Cross – creator of the cowhide stilettos – speak to Rocha’s Irish heritage, while the paintings by Cassi Namoda and Sian Costello of girls in diaphanous dresses carry echoes of her own silhouettes. The Gothic, art-filled Lismore Castle, aside from being a favourite haunt, also provides the perfect setting for the artworks, which are arranged as if in a dialogue in different rooms. (When we speak, Rocha is considering suspending the Bourgeois piece, Janus in Leather Jacket, in the space’s round room, “because she’s almost like the matriarch of the show”.)

Here, Rocha talks about her attitude to curating, her ongoing love of Bourgeois, and her formative experiences with art and artists.

Laura Allsop: I was wondering if you could tell me a little bit about the very evocative title of the exhibition?

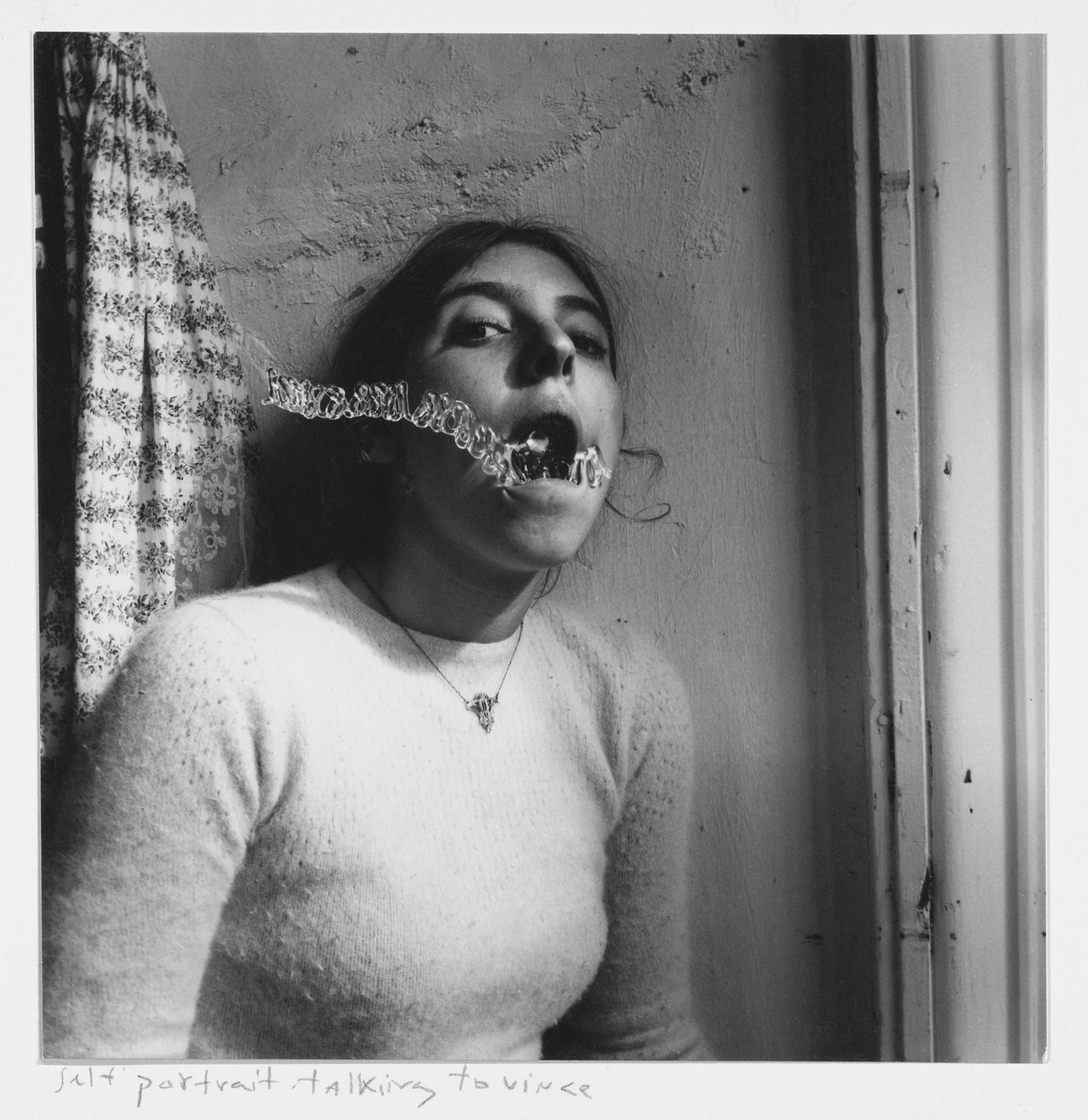

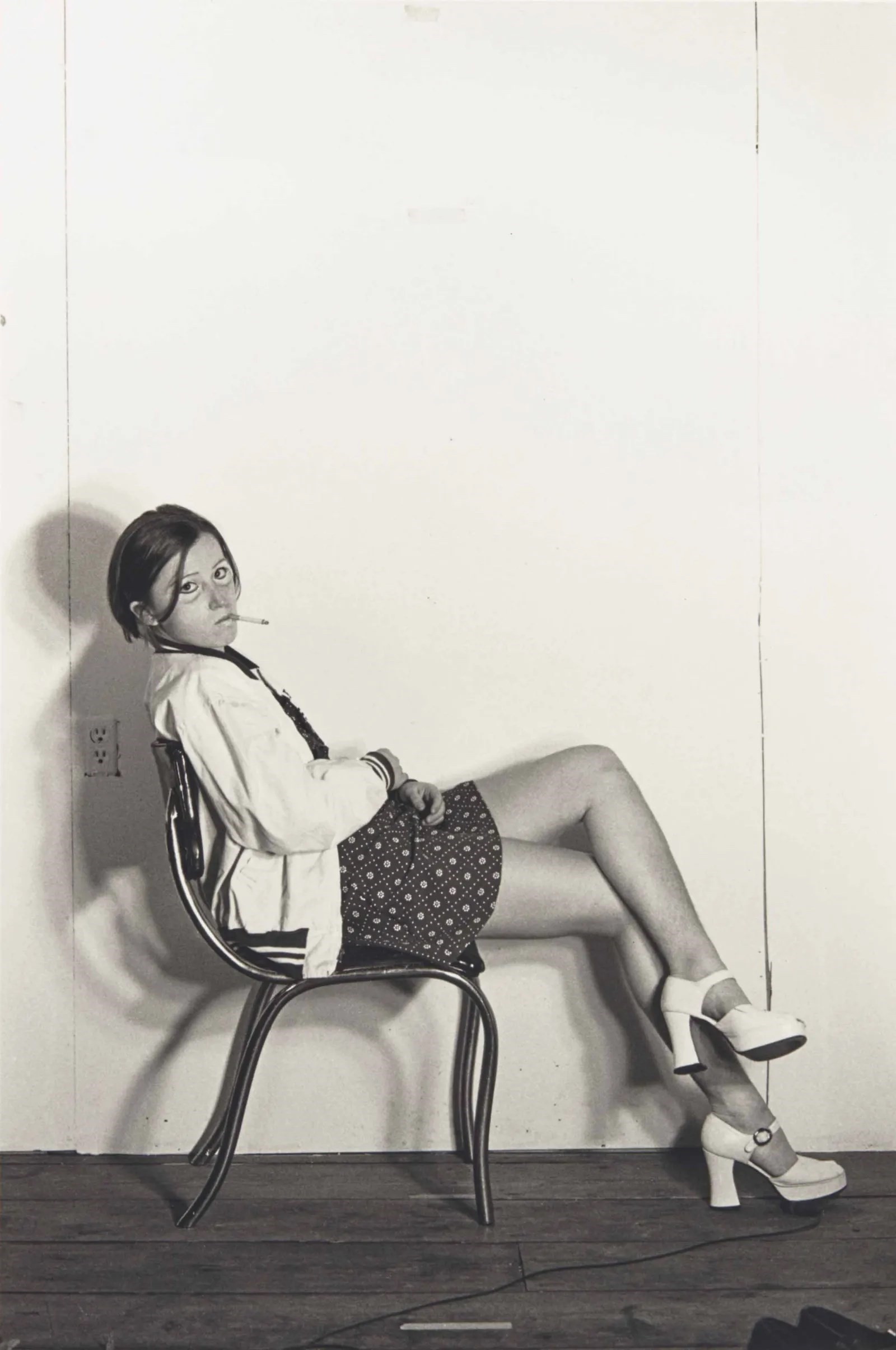

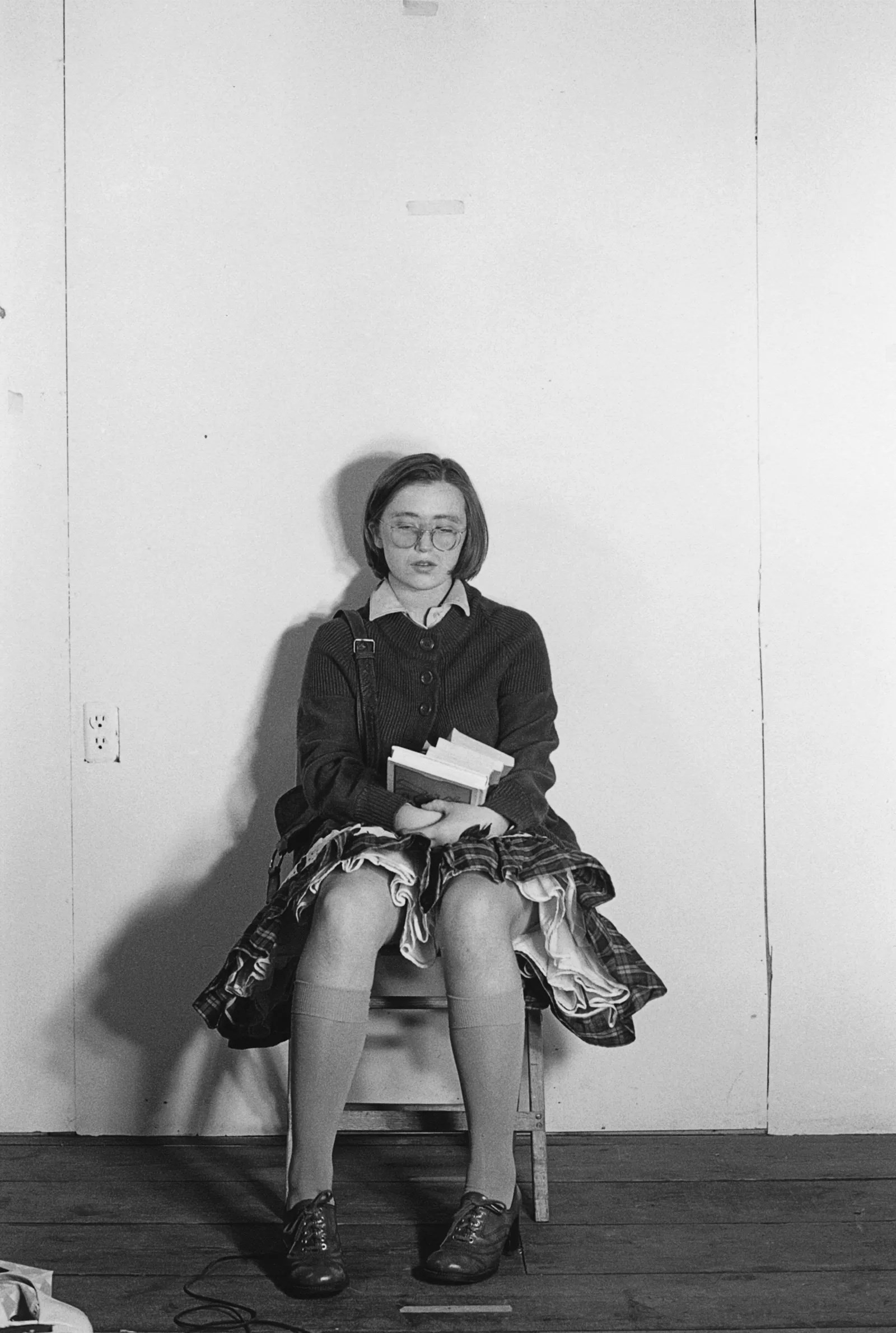

Simone Rocha: It’s an all-female show. And the artists that I picked, I feel a lot of their works are self-portraits. Even though they’re not self-portraits, I think you can really see the person behind each one. Behind their provocativeness, there’s also a slight sense of humour, almost like a dark humour running through. And I felt that girls girls girls really encapsulated this mix of different generations of women – dead, alive, young, old. It feels like a coming together, and I also love that it does have a slightly provocative, playful, dark tone to it.

LA: How did you go about making your selections for the show?

SR: I wanted to approach it in a very natural, authentic way and pick works that I felt personally drawn to. So some of the very first works were by people that I have collaborated with, from Harley Weir and Roni Horn to Louise Bourgeois’s estate. That was the starting point, but then as it developed I wanted to introduce other works to balance it out: people that I really admire, like Cindy Sherman and Alina Szapocznikow, with her amazing latex sculptures, which I really didn't think we were going to get. I also wanted to bring in some younger artists, like Sophie Barber, whose works I discovered three years ago through the curator Sarah McCrory, and Josiane Pozi, a young graduate filmmaker. And then because we're on home turf, I wanted to work with some Irish artists, so I invited Genieve Figgis, Dorothy Cross and Eimear Lynch, who I’d actually just worked with on my last show. So it was a nice mix of the really established to some people that are very unknown.

LA: A lot of the artists chosen use their bodies performatively, or treat the body very viscerally. What fascinated you about the way these women use the body?

SR: I think what is amazing is the physicality of the works. Harley’s work has a breast, Sharna [Osborne’s] work is a torso, Louise’s work is a Janus. It was going back to this idea of things being physical and tactile and seeing people look to the human body as a vocabulary. I found that really interesting and it was just something that I noticed as I was selecting; the female form naturally started working its way in. Even the fact that in Josiane’s video work, she’s always the subject, same with Cindy Sherman – it’s her physically taking on these other identities.

LA: I’d love to talk to you a little bit about the garments that we can see in some of the works, like those Dorothy Cross stilettos.

SR: They’re amazing and they’re made from a cow’s udder! I love that they look almost preserved, like the Iris Häussler work of these clothes preserved within wax – which was another piece that we didn't think we were going to get and so I was thrilled we did. Obviously clothing and garments are such a big part of my process; it just felt natural to be attracted to some works that are very physically garments. And then in other works, garments are their own character, like in Cassi Namoda’s painting of the girls in blue. Even in the Elene Chantladze works – they’re very abstract with this incredible naiveté and depth and almost sorrow to them. But the way that the figures are dressed and the colours and the way they’re all balanced, there’s a real sensitivity to it.

LA: What does girlishness as a concept mean to you, and do you think it’s something that’s constrained by age to girlhood?

SR: No! I think it much more conjures something provocative than something soft. Even someone like Louise Bourgeois, who was incredibly serious about her work – you can see in it as well this sense of mischief.

LA: Can you remember the first piece of art you saw that really captivated your imagination?

SR: The piece that I really was blown away by when I was in school was Francis Bacon’s studio at The Hugh Lane in Dublin. They moved his studio piece by piece and rebuilt it inside the gallery. It’s still there. It’s like a maze. I think it was that it was so unapologetic; that this was the habitat for creating all these works, and how the work kind of bled from within him onto the pages or onto scraps of paper and onto the fridge and onto the kitchen sink. I just thought it was so sincere, and also so sinister, but then it created something so beautiful.

LA: Do you have a favourite museum or collection you like to go to for inspiration?

SR: I always love going to the Maeght Foundation in the south of France. They have original [Alexander] Calder sculptures that are there permanently and they have different shows, but it’s also the whole building and the experience of going up a big hill to get there. And then not too far from it is the Matisse chapel, which he painted and did the stained glass windows. That’s a little pilgrimage that never disappoints; it makes you feel very small. And they’re not big, ‘zhuzhy’ buildings, they’re very low key, but they’re amazing and I love them.

LA: When you’re looking at artworks, do you find yourself honing in on particular things?

SR: I love hands and feet. And that’s another thing that I always loved about Louise Bourgeois’s work. Jerry [Gorovoy, Bourgeois’s assistant] was telling me that she was really, really good at drawing feet because she had to do so many tapestries of feet. I also love very thick paint [laughs]. I get very, very close. It’s always like – how close can I get to the glass?

girls girls girls at Lismore Castle Arts opens on April 2 and runs until 30 October 2022.