David Wojnarowicz’s rage was a big part of what made him famous as an artist, writer, filmmaker and photographer. In 1987, after discovering he was HIV-positive, the fury that defined much of his early work was exacerbated, culminating in one of his most famous pieces; Untitled (One Day This Kid ... ), a vicious, poetic indictment of homophobia and the American government’s mishandling of the Aids crisis. Two years later in 1992, Wojnarowicz died of the virus – just like his close friend Peter Hujar, who passed away five years before from Aids – and who David had controversially photographed just moments after his death.

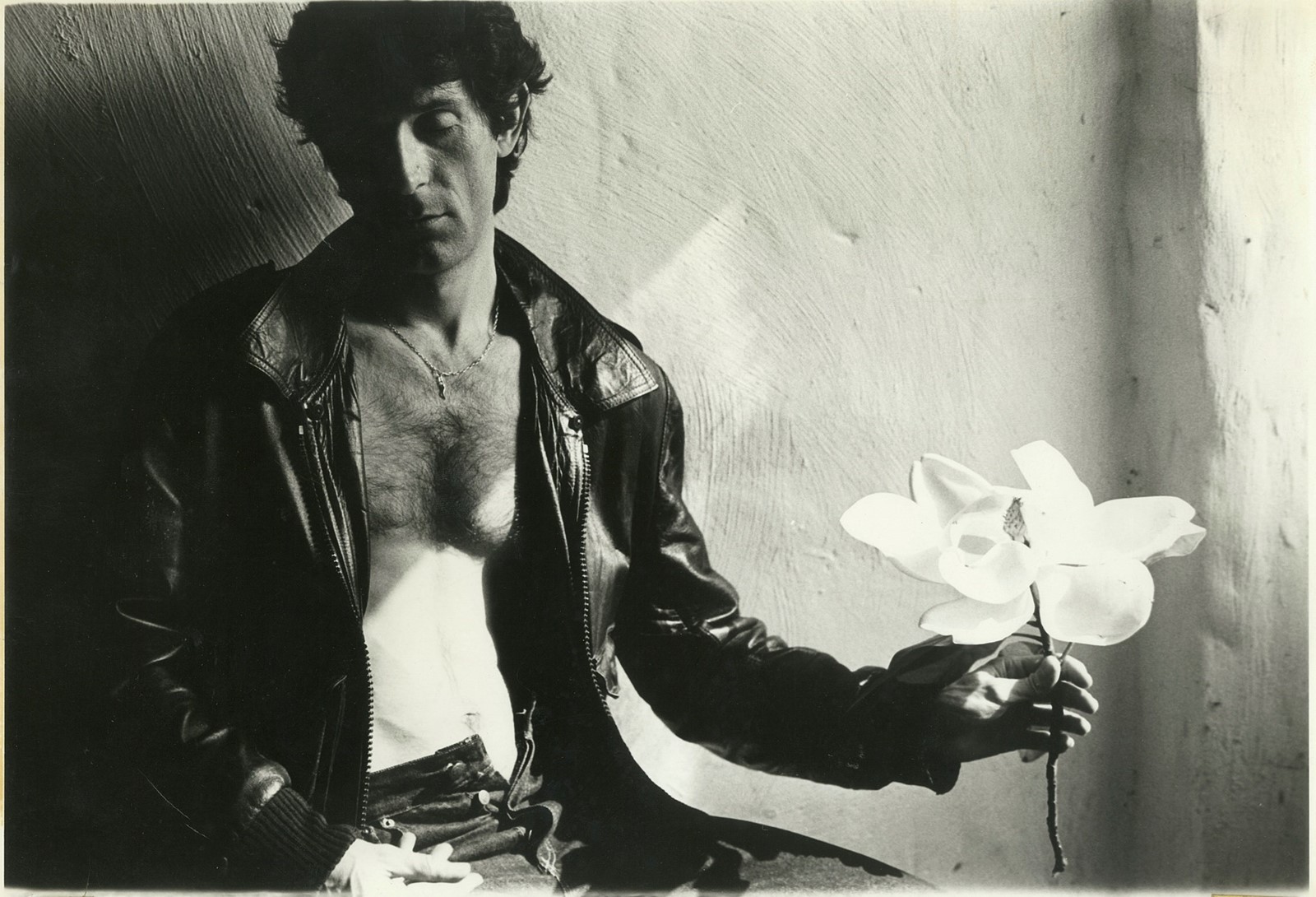

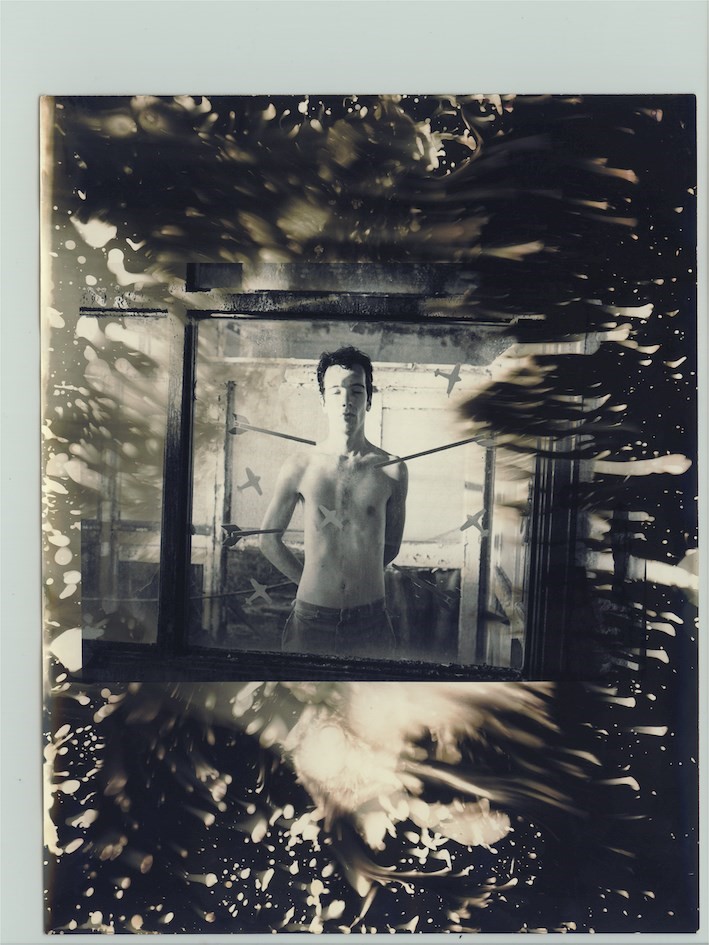

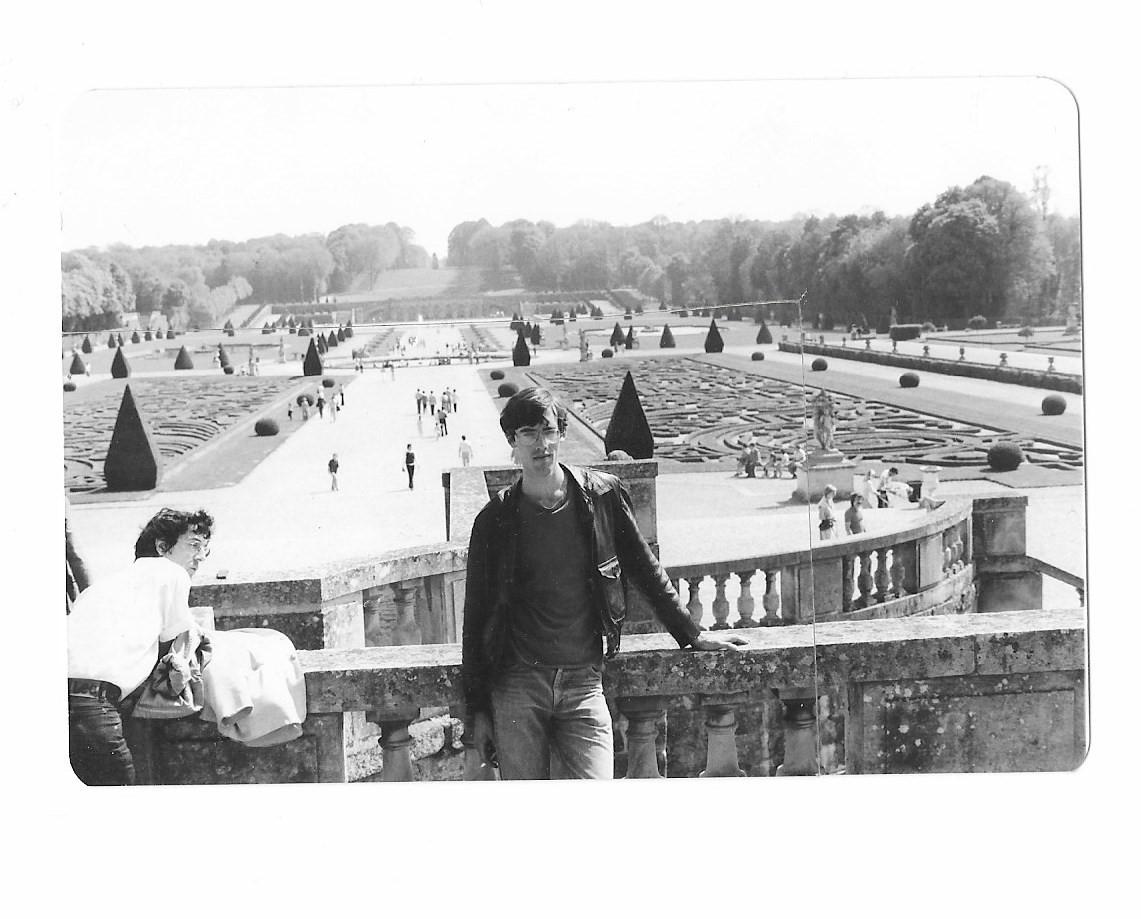

Wojnarowicz’s tenderness, however, was equally as powerful as his fury. A new exhibition at PPOW Gallery in New York, Dear Jean Pierre, displays previously unseen letters sent by Wojnarowicz to his Parisian lover Jean Pierre Delage between the years of 1979-1982, alongside sketches and photographs – one photo of a shirtless Jean Pierre holding a flower has a hint of Robert Mapplethorpe to it, while images of David at the infamous Hudson River ‘art pier’ and early Arthur Rimbaud in New York prints show a young artist coming into his own.

Cynthia Carr, who co-curated Dear Jean Pierre with Anneliis Beadnell, knows more about Wojnarowicz than most; her 2012 biography Fire in the Belly chronicled the late American artist’s fraught upbringing in New Jersey, and his subsequently colourful life in New York. Carr also knew Wojnarowicz personally, after meeting him while writing about art for The Village Voice in the 1980s and 1990s. “David’s integrity always comes through,” she says. “The way he dealt with all these issues in his life, and cared about expressing that more than he cared about making money.” Likewise, PPOW Gallery has a rich history with Wojnarowicz – in 1989, founders Wendy Olsoff and Penny Pilkington exhibited his solo show In The Shadow of Forward Motion – while Carr says “PPOW is the only gallery that survived the [gentrification of the] East Village.“

Below, Carr talks about living through the East Village’s artistic heyday, Jean Pierre’s letters, and why Wojnarowicz’s work continues to be a balm for a world in crisis.

Violet Conroy: How did you first come across David’s work?

Cynthia Carr: The first things I saw were the stencils he did on the street back in 1981. He was in that band 3 Teens Kill 4, and started doing stencils to advertise their gigs. At that point, so many artists were working on the street; Keith Haring was doing all those drawings in the subway and on the street, Jenny Holzer was pasting her aphorisms up, Jean-Michel Basquiat was doing the SAMO stuff, and David was doing stencils like the burning house and the aeroplanes.

Later, I met David through my friend Keith Davis when I was working at Artforum. David came in one night to borrow money from Keith, and I knew he was the one that did the stencils. Next summer, Keith took me to the art pier off Canal Street. David had been working there for a couple of years already, but by then they had opened it up to other artists and lots of people were fighting over which wall they would get. It was still very exciting. The pier was completely outside of the gallery system, which David loved of course. People were just working on the walls, nothing was for sale, nothing could really be bought, although people were coming in and trying to chip things off the walls. It was a really funky space, there were holes in the floor where you could fall into the river if you weren’t looking out for your step.

VC: At what point did you begin writing for The Village Voice?

CC: I was doing design at The Village Voice, and I said: ‘You really should be covering the galleries in my neighbourhood. This is a big deal.’ They said, ‘Well, write something if you want.’ That was in 1984, and I went to all the galleries and did the first piece about the East Village scene. This was a ‘bad neighbourhood’ when I moved here, there was a lot of crime right down the street from me. According to The New York Times, it was the ‘epicentre of the world heroin trade’. There were lots of abandoned storefronts. It was a really wonderful thing, people who’d never had any experience at a gallery before decided to take these storefronts and open art galleries.

VC: Your biography [Fire in the Belly] about David came so much later. Why did you decide to write about him and what was that process like?

CC: I did the biography because his boyfriend, Tom Rauffenbart, who at that point was the executor of his estate, asked me to write it. Someone once said, ‘These aren’t biographies, they’re cultural histories,’ and I think in a way that really is true. The context is important, so in the book about David, I could write about the East Village scene, which by then had pretty much disappeared. I could write about the culture wars here and the Aids crisis, both of which I had covered quite extensively at The Village Voice.

After that, I got to know him a little better. When I heard that he was really sick, I called him up and said, “If you need any help, I’ll do whatever you need.” I was told that he didn’t want anyone to visit him. He did go through periods like that, where he was just isolating. He would occasionally call me, and would talk about whatever was going on with him, the newest horrible turn in his illness, his ideas. I went to visit him when he was in the hospital, and that’s when I met Tom, the boyfriend. In retrospect, I feel very lucky because he had kept out a lot of his old friends from the scene, but he was allowing me and a few people to come over. Then, years later, Tom asked me to write the biography.

“You could see that Jean Pierre was this emotional centre for him, and someone who he felt would support him even at that great distance” – Cynthia Carr

VC: Why do you think Tom asked you to write David’s biography?

CC: He thought it would be helpful to get David’s story out. I have to say, when that retrospective happened at The Whitney [History Keeps Me Awake at Night in 2018], one of the curators announced publicly that the retrospective would not have happened if I hadn't written the book. I think it made David understandable.

VC: How did the new exhibition Dear Jean Pierre come about?

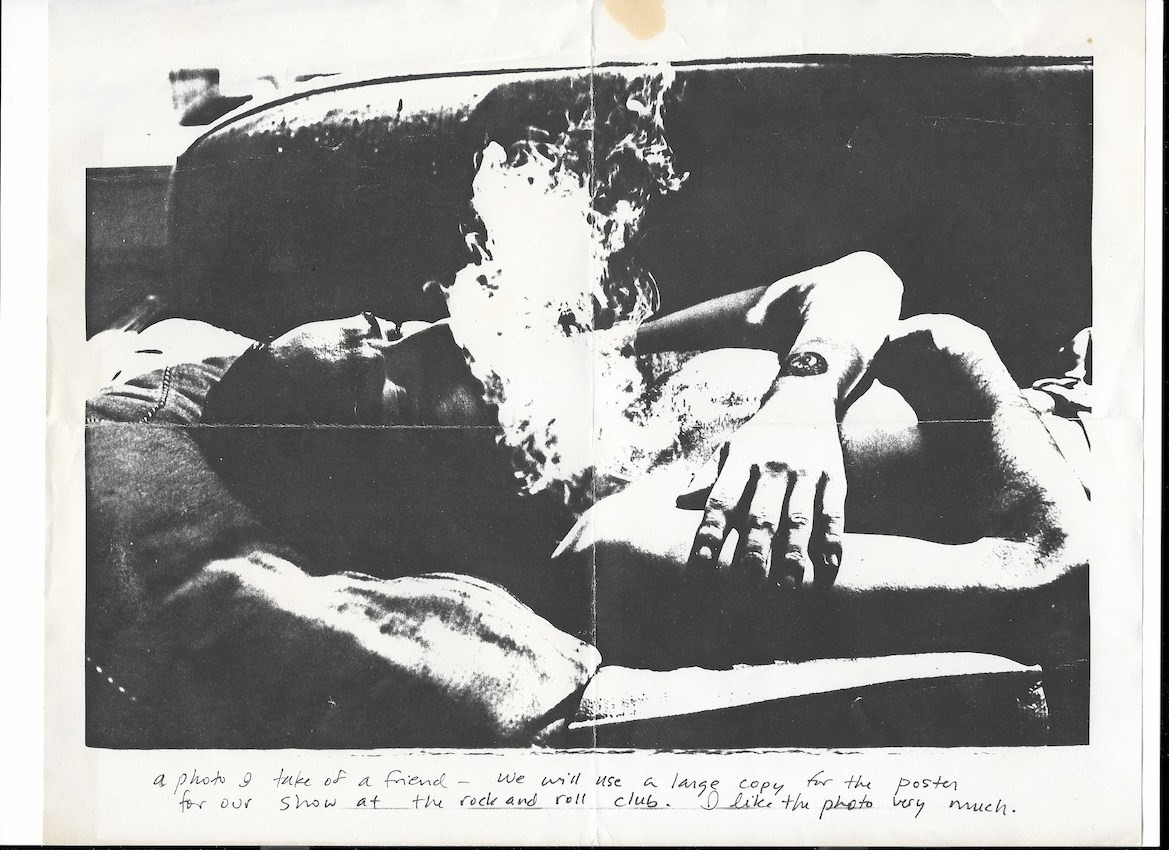

CC: I told Wendy [Olsoff] and Penny [Pilkington], the gallerists that founded PPOW, that Jean Pierre has all these letters. I went to Paris and scanned all of them in 2008. They were so valuable in terms of writing the book, because that’s where he was talking about how he was making a living, where he was living, and what the new work was. He talked about the Arthur Rimbaud in New York pieces, and how he wanted to make a film called Heroin. I found all these Rimbaud pictures that David had sent him, and they were printed small because David couldn’t afford the paper. I remember saying to Jean Pierre, ‘Do you know how valuable these are now in the art world?’ He said, ‘I don’t care. I’m not selling anything ever.’

Jean Pierre told Wendy and Penny, ‘If I die, my family will come and they’ll just throw everything away.’ He agreed to try to get them placed in an archive, and that’s the purpose of the show.

David would make drawings on these letters, and he wrote to Jean Pierre a lot. You could see that Jean Pierre was this emotional centre for him, and someone who he felt would support him even at that great distance. At that point, in 1980 or so, it was very expensive to make a long-distance call from New York to Paris. David never had any money. We certainly didn’t have Zoom or cellphones or Facebook or any of that stuff – everything had to be done by letter.

VC: Why is David’s work still important today?

CC: I think it’s because of the way he dealt with crisis, the disasters we’re in right now with war and climate change and everything else, it’s like a world in crisis. For David, Aids was a crisis, and Aids changed the world for the worse. David was there, speaking personally and truthfully, in his art and in his writing, in Close to the Knives. It makes a difference when someone is there and is saying: ‘I see you. I see what you’re going through. I’m going to paint it, I’m going to write it.’ Most of the ACT UP group were sick and they knew they were going to die, but they still tried to have this political group about it. David’s integrity always comes through; the way he dealt with all these issues in his life, and cared about expressing that more than he cared about making money. His work was always from the heart.

Dear Jean Pierre: The David Wojnarowicz Correspondence with Jean Pierre Delage, 1979-1982 is on at PPOW Gallery until 23 April 2022.