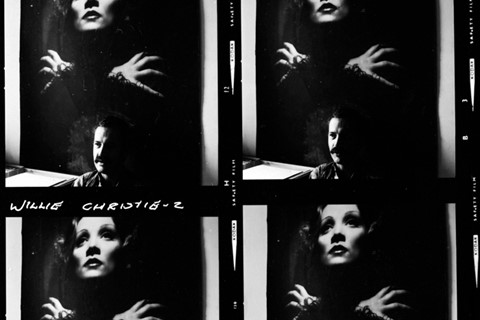

To mark a new exhibition of his work, we speak to legendary photographer Willie Christie about Grace Coddington, Pink Floyd and more

Willie Christie was responsible for some of the most memorable glamour images of the late-70s and early-80s, and this month an appointment-only exhibition opened at The Ivy featuring images of Jerry Hall, Mick Jagger, Catherine Deneuve, David Bowie and his ex-wife and muse Grace Coddington, to name but a few. Although Christie’s work is incredibly slick and its prevailing focus is upon the glamour models and celebrities of his era, it contains a beguiling otherness that travels far beyond the fashion sphere and poses questions about reality, identity and artifice. His carefully constructed images place his subjects in all-too-perfect frames that leave a surreal and at times almost sinister aftertaste, which may be the one of the key reasons he attracted the attention of Pink Floyd, who enlisted his skills for their short film The Final Cut. Here, the photographer and filmmaker, who has kept the images in the exhibition under-wraps for 35 years, talks to John-Paul Pryor about shooting the ultimate Vogue girl, telling stories and his childhood desire to recreate life’s stage.

How young were you when you first picked up a camera and decided it was the medium you wanted to use to communicate with the world?

I was pretty young. And in fact, I’ve still got the camera – it’s a little old movie camera that belonged to my uncle who was killed in the war. I found it at my grandparent’s house and it was like a ‘eureka’ moment! I guess I must have been six, seven… eight? I had no idea what it was for. I just knew that I wanted to buy film for it. I never actually got it working but I’ve still got it. I also remember being much younger – four or five – and finding a very old-fashioned cardboard build-your-own-theatre at my grandparent’s house. I remember being fascinated by that. I wanted to be an actor when I was in my early teens and I was kind of laughed out of court… I don’t know. I just wanted to do shoot pictures and I didn’t understand why or how – I wanted to do movies; I wanted to tell stories.

In a sense, did you want to create your own stage?

Yes, I think so. Because there’s a certain sort of artifice to my work and the way I used to light was really influenced by Hollywood movies – the old black-and-white movies. I just loved Hollywood and the artifice of it. I suppose it was supposed to be real life, wasn’t it? But it was so artificial! Fantastic stuff! I still love it.

It’s interesting you say that because your lighting creates kind of a dreamscape – something reaching for the sublime that isn’t quite human. Do you think people strive to make those kinds of ultra-perfect fashion images into a reality?

Yeah, I think so. Hmm... Well, I suppose so because it’s aspirational. If you look at Bailey, for example, then you can see that everything that he brought to fashion was very much the zeitgeist, or it became the zeitgeist – I mean, which came first? Did he sort of invent it? I guess we do take on what we see, and we’re certainly influenced by what we see. I remember going to see Raging Bull – a million years ago – and there were all these blokes waiting to see it being all punchy, heavy and macho. At the end of the film they came out kind of defeated, quiet and docile. It was the first time I’d ever really noticed people being really affected by something.

There is a sense of telling a story in some of your portraiture – how do you approach your subjects?

I think for me it was about setting a mood. I mean, I think I set a mood in lighting really. I’d be interested to know how I would do portraits now. I often think I’d really like to do a new series of portraits. Bailey does fantastic portraits, even in the studio, because he has such a rapport with people. But I don’t know if I could do that. For me, it’s probably a kind of fallback on to using the stage as a prop, or that perhaps the stage itself is actually saying something about the people. When I shot Bowie and Catherine Deneuve for The Hunger, I read the script and I looked at the rushes. I knew what was going on and I was trying to interpret what they were doing in the film in the image.

Your ex-wife Grace Coddington brought you into the fold at Vogue. How did it feel to kind of have your life flip into that high-end fashion world?

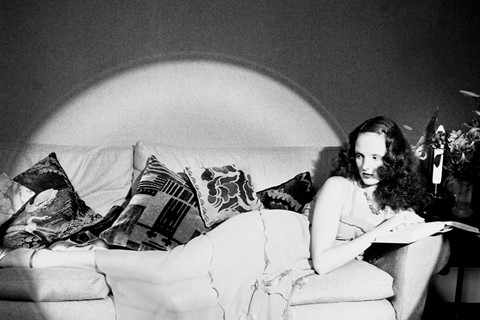

Well, I guess I had had about three years of doing stuff. I was working at Over 21 and Vanity Fair when I met Grace. We started doing a few pictures together because I just loved her look and there were some images that I had in my mind I wanted to do. It was a little bit of me experimenting and she enjoyed doing it. There was no pressure, and if it didn’t work out we shot again. I think those images all slightly came from Hollywood. She was a perfect Hollywood muse at that time, you know? In terms of how it felt? I suppose I just suddenly got there and, like a lots of things in life, you don’t realise how fantastic it is when it’s happening – then you start concentrating on the fact that you’ve got to do it and suddenly you get everything at your fingertips. It’s like a lot of things in life. I think you look back and think, ‘Wow, I am really lucky. I’m a lucky old bastard.’

Do you think glamour was more innocent in the era when you were shooting fashion?

Yeah, I think so. I hadn’t really thought about it for years until I started getting the photographs out there again. Things were very different back then though – the mood was very different. Fashion had kind of a twinkle in its eye because it was fun – it was kind of 'glamorous fun' and it wasn’t really taking itself terribly seriously. Looking through fashion magazines now I do feel that there’s less of a statement there – everything seems to look very much the same and I’m not quite sure whether that is because of Photoshop or the influence of fashion editors – maybe it’s just fashion itself, maybe just the whole feel of fashion and what people want from fashion is different.

Did it feel good to move away from fashion with your work for Pink Floyd?

Yes, I mean, that was great for me. I knew all the time that fashion was not the be-all-and-end-all of everything for me. That was my first kind of real move into movies. I first worked on live stills for 'Shine On You Crazy Diamond', and I kind of did that with Gerald Scarfe because he started doing stuff for them before The Wall. I can’t remember when it was now, but we sort of worked on bits of that together and put this piece of film together for that big round screen they toured with in the late-80s. When I saw 15, 000 people watching it and applauding – they weren’t applauding the film (laughs) but they were applauding the effect – that was really something. That was great, and that was the start of really telling stories.